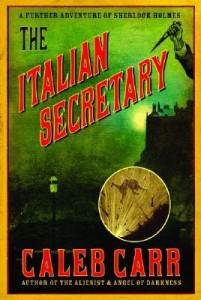

With the festive season now upon us, I invite you to pause for a moment as we continue our tribute to The Italian Secretary — Caleb Carr’s contribution to the Holmes legacy — for its 20th anniversary this year. Last month, we began this series by exploring how Conan Doyle’s interest in Spiritualism, and its subtle influence on the original Holmes canon, helped to inspire the supernatural thread that runs through the novel. Yet, as we learned in Part One, there was far more to Caleb’s choice of subject matter than this alone.

In the novel’s afterword, the U.S. Representative to the Conan Doyle Estate, Jon Lellenberg, explained that The Italian Secretary had originally been commissioned to form part of a short story collection he co-edited, Ghosts in Baker Street. Caleb, a lifelong Sherlockian, had been invited to contribute; however, the deeper he delved into the real historical crime he’d selected as inspiration, the richer (and longer!) his contribution became — so much so that the decision was made to publish it as its own novel.

In today’s post, we therefore move away from the supernatural (if only briefly) to learn what it was about the 16th-century murder of David Rizzio, the titular “Italian secretary”, that captured Caleb’s imagination. It is a story that draws us back to the Edinburgh of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a tower where a ghastly deed took place…

Northward to the Scottish Border

“Furious stabbings… bombs… Holmes, what in Heaven’s name are we entering into?”

The Italian Secretary, Chapter 4

Holmes glanced up and out of the window. “Scotland, I should say…”

To understand why Caleb chose to center his Holmes tale in Scotland, we need look no further than the novel’s dedication. Beyond his beloved feline companion at the time, Caleb credited Hilary Hale, his editor in London, as the person responsible for his visit to the location that ultimately became the setting for The Italian Secretary: the Royal Palace of Holyroodhouse. He explains how this happened in the Acknowledgments section:

“I could not have known, when she dispatched me to Scotland once on a book tour, that a chance visit to the royal palace of Holyrood would one day become this story; but I do know that without the hard work, infinite patience, and support of Hilary (and of her brilliant co-workers at Little, Brown UK), that trip would probably never have taken place.”

The tour Caleb is referring to took place several years earlier, at a pivotal moment in his career. According to The Bookseller, the unexpected success of The Alienist meant that his UK publisher had decided to give its sequel, The Angel of Darkness, considerable backing when it was released in early 1998. In addition to a first print run of 25,000 copies, it also received an international book tour. Starting in Ireland before crossing to London, Caleb gave talks at the Waterstones branches in Dublin, Manchester, Leamington Spa, and Edinburgh. It was the Edinburgh leg of the tour, which took place on March 13, 1998, that would prove fateful, as it marked Caleb’s first visit to the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

The Secrets of Holyroodhouse

“I went also to see Mary Queen of Scots’ Bedchamber (a very small one it is) from whence David Rizzio was drag’d out and stab’d in the ante room where there is some of his Blood which they can’t get wash’d out.”

Elizabeth, Baroness Percy (1760)

The Palace of Holyroodhouse (also known as Holyrood Palace) dates to the early 16th century when it was constructed by James IV. Located beside the Augustinian Holyrood Abbey that was erected several centuries earlier in 1128, it is said to be named either for a vision of the cross King David I had while hunting in the area, or for a relic of the True Cross (known as the Holy Rood) that belonged to his mother, Saint Margaret. Unlike the vast ceremonial palaces more commonly associated with the British monarchy, Holyroodhouse has always been an intimate and lived-in seat of power, with its private apartments closely interwoven with its public spaces. While the public may be more familiar with Balmoral — the current royal family’s favored private Scottish estate — Holyroodhouse has long been the official royal residence in Scotland, a tradition that continues to the present day.

Although Caleb never publicly discussed his tour of Holyroodhouse, it seems likely he would have had an experience just as affecting as other visitors have reported for over two hundred years. According to the Royal Collection Trust, public fascination with the doomed reign of one of the palace’s most intriguing monarchs — and a central figure of The Italian Secretary — Mary, Queen of Scots, has attracted visitors since the latter half of the 18th century. From these earliest years, visitors to Mary’s former private apartments have been confronted with the gruesome sight of bloodied floorboards, the last remaining evidence of the murder of David Rizzio, her private secretary. As this murder forms the basis for The Italian Secretary, it seems plausible that this remnant from the palace’s violent past may have served as Caleb’s first direct inspiration for the story during his visit.

Given that Caleb included a vivid description of how the 1566 murder of Rizzio took place in the novel, I will avoid going into detail here in order not to ruin the book for readers who may not have familiarized themselves with the tale. However, for the sake of providing historical context and wonderful visuals of the palace itself, I strongly recommend watching the following video from the Royal Collection Trust, which opens with a brief summary of the famous assassination:

What gave the murder of David Rizzio its unusual longevity was not only its brutal nature and political significance, but the way it continued to haunt Holyroodhouse itself — quite literally. Indeed, this may be another reason Caleb decided to feature the story. Over the centuries, rumors have persisted of disturbances and apparitions at the palace tied to the murder. In addition to the bloodstained floorboards where Rizzio’s body had lain after his death (the boards have been replaced several times, with the stains said to reappear in the same location each time), a ghostly figure attributed to the secretary has been observed in the area. But Rizzio is not the only spirit tied to the killing who has been said to linger within the palace walls.

Not long after the secretary’s death, Lord Darnley — Mary’s husband and one of the instigators of Rizzio’s assassination — also met a violent end. Although initially believed to have died in a house explosion while recovering from illness, his body showed signs of strangulation. Suspicion for the murder fell on Mary and her future husband, the Earl of Bothwell, though it was ultimately several of the Earl’s servants and acquaintances who were found guilty and executed. Of relevance here, as with the secretary he helped to dispatch, Lord Darnley’s spirit is also said to haunt his former rooms at Holyroodhouse.

Whether one lends credence to such stories or not, they form part of the accumulated atmosphere of Holyroodhouse, a place where history, intrigue, and the unexplained overlap. For a writer like Caleb, it is easy to see how this charged setting might have suggested itself when he was invited to write a Holmes story with an other-worldly element. In this light, his decision to center The Italian Secretary on the murder of David Rizzio seems less an imaginative leap than a natural convergence: his interest in Conan Doyle’s metaphysical curiosity (see Part One), his book tour to Edinburgh, and his lifelong fascination with history all pointing in a single direction.

I hope you have enjoyed exploring some of the inspirations for The Italian Secretary. To conclude the year and our celebration of the novel’s anniversary, in Part Three we will give our imaginations room to roam as we consider what might have happened had Caleb followed Jon Lellenberg’s suggestion in the novel’s afterword and brought the worlds of Holmes and Kreizler together. I trust you will join me then, but in the meantime, happy reading!