Here we are again at the close of another year. New Year’s Eve in 2014, however, is a particularly noteworthy date for 17th Street. Not only does it mark the conclusion of the 20th anniversary year of The Alienist‘s publication, it also marks the 9th anniversary of the website. In consequence, I’m pleased to be presenting the final part of the special three part blog series overviewing The Alienist‘s central themes in honor of both milestones.

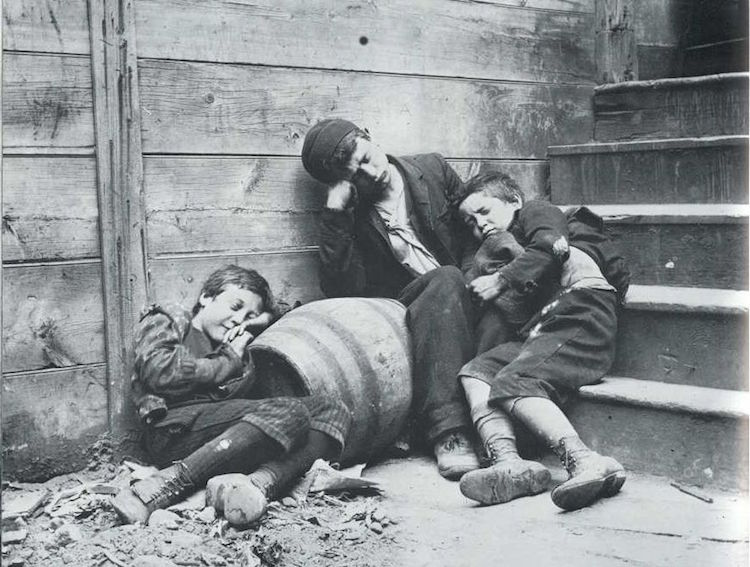

In the preceding two parts of the blog series, we have explored several of the novel’s central themes, ranging from corruption and hypocrisy to domestic violence and childhood trauma. As we conclude the series in Part Three, we will continue the discussion begun in Part Two that the role of the mother was one of the key differences between the early childhoods of Dr. Kreizler and John Beecham, leading us to explore themes in the novel relating to the role of women in society, the role that mothers can play in domestic violence and childhood trauma, trust and betrayal, regaining control, psychological determinism, and changing the way we think about mental health.

N.b. The following post contains major spoilers for The Alienist. To read a spoiler-free synopsis, please refer to the summary page.

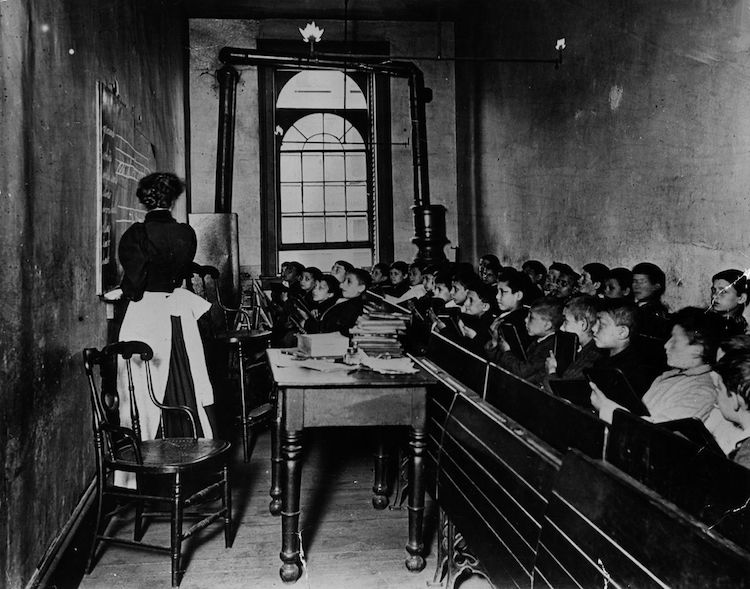

The Role of Women in Society

Although it may seem as though The Alienist‘s sequel, The Angel of Darkness, is the stronger of the two novels in terms of themes tied to the feminine—that is, in its examination of what drives women to kill—it would be a mistake not to acknowledge that the role of women in society, and the role that mothers can play in domestic violence and childhood trauma more specifically, are themes that are as prominently placed in the original novel as in its successor. As early as Chapter 5 in The Alienist when we are introduced to Sara Howard, a close childhood friend of John Moore and one of the first female police secretaries, the unique experiences—and frustrations—of women in New York society of 1896 are brought to our attention.

“Sara—with all the professions open to women these days, why do you insist on this one? Smart as you are, you could be a scientist, a doctor, even—”

“So could you, John,” she answered sharply. “Except that you don’t happen to want to. And, by way of coincidence, neither do I.”

The Alienist, Chapter 5

Sara’s inclusion in the novel as an intelligent, fiery, competent, and determinedly single-minded woman with the goal of becoming New York’s first female police officer is no accident. While her employment in the novel as police secretary is a clear nod to Theodore Roosevelt’s controversial decision to hire a female secretary upon becoming Police Commissioner (his real secretary, Minnie G. Kelly, was “young, small and comely, with raven black hair”; see 17th Street’s Island of Vice book blog for more information), she is also representative on a more general level of those women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who had begun to push back against the prevailing view that the only proper role for women in society was as a doting wife and mother in the home; an ideology that had dominated American culture from the late eighteenth century onwards (see 17th Street’s Education of Sara Howard history blog series for more information). However, it is important to note that Sara’s purpose in the novel in terms of social commentary is not strictly historical, as Caleb Carr pointed out in an interview with Salon in 1997:

I wanted to write a book with a female character whose reasons for being in the story did not depend on her falling in love with somebody. Women are still being brought up to believe that they have to build their bodies and their minds toward relationships and not toward independent existences of their own choosing. And I wanted to show that women can do that.

I, for one, appreciate Mr. Carr’s stance on this topic. Only last month The New York Times ran a piece pointing out that despite the bleak statistics on marriage, a large number of young women still see the “fairy-tale wedding” as their crowning moment in life, with the wedding gown continuing to be viewed by many as “the most important dress in the life of a woman,” as Oscar de la Renta stated in a recent Vogue magazine spread. As the author of the NYT piece pointed out, “He probably wasn’t considering what a woman would wear, say, as she accepted a Nobel Peace Prize, or was being sworn in as the president of the United States.” Clinical psychologist Sue Johnson went on to explain this mentality in the NYT piece using language strongly reminiscent of the woman’s sphere ideology of the nineteenth century, “Hillary Clinton might be the first female president, but a woman still wants this badge of legitimacy that she is wanted and desired by a man.” Accordingly, the inclusion of an independent female who remains single by choice in a bestseller such as The Alienist is a breath of fresh air, even if, as Dr. Kreizler observes to John:

“Women of such temperament,” he said as we moved to the carriage, “do not seem fated for happiness in our society. But her capabilities are obvious.”

The Alienist, Chapter 9

“There is more than one type of violence, Doctor.”

Taking the role of women in society one step further, one of the less well-recognized themes in The Alienist is the role that women, specifically mothers, are capable of playing in domestic violence and childhood trauma. Although most readers would recognize this theme from The Angel of Darkness where the murderer was a woman who, lacking Sara’s financial freedom and family support, had been expected to fulfill the role of wife and mother—a role to which she was wholly unsuited, and was unable to come to terms with—the theme is, in fact, just as important in The Alienist.

| Continue reading →