The Angel of Darkness, 210:

Would Mike be able to detect if the person was in fact in the house, and find the right room? Indeed he would, Hickie said; in fact, it would be a breeze, compared to some of the jobs Mike’d handled in the past. Then I asked about the training, and was surprised to learn how simple it would be: all I’d need would be a piece of clothing from the person I was looking for, the more intimate the better, as it would be that much more steeped in the person’s scent. Mike was already so well trained that when he began to connect a particular object or smell with his feeding, he quickly got the idea that he was supposed to find something that looked or smelled the same; only a couple of days would be needed to get him ready.

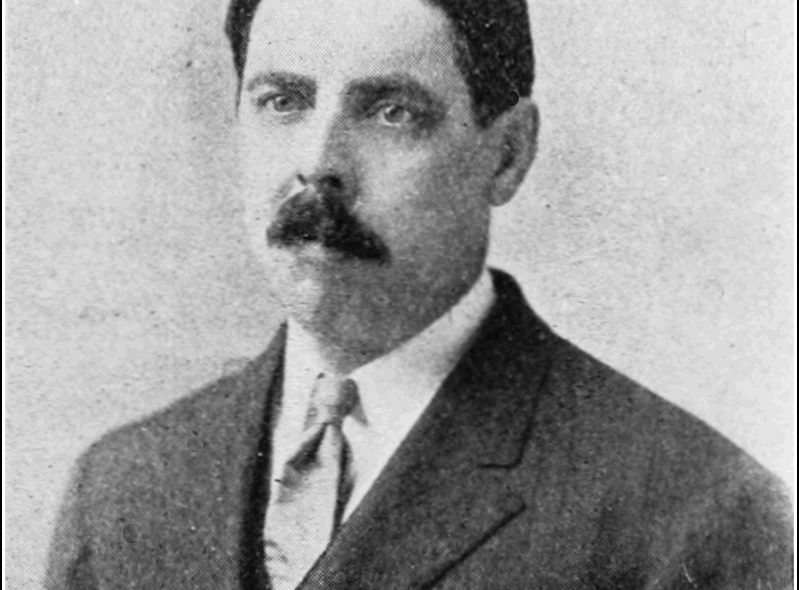

As we discussed in Part One, we can see from this extract that Hickie was using meat as a means of rewarding Mike for performing a desired behaviour, a technique that would come to be known as positive reinforcement from the 1930s onwards when another renowned American psychologist, Burrhus F. Skinner, established operant conditioning as the other half of ‘behaviourism’, a field of psychology John B. Watson had popularised in the 1910s on the basis of Pavlov’s classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning. However, three decades prior to Skinner, another American psychologist, Edward Lee Thorndike, was conducting the research that would form the foundation of Skinner’s work. Thanks to Thorndike’s innovative methods, his research would take the world of psychology by storm when it was first published in 1898, and within the year he would have publications in the prestigious generalist journal Science and the equally prestigious specialist journal Psychological Review, and would be invited to present his work at both the New York Academy of Sciences and the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association. Little did Hickie the Hun know that he had anticipated what would become one of the most important and revolutionary ideas in animal and human learning — no wonder Dr. Kreizler was impressed! | Continue reading →