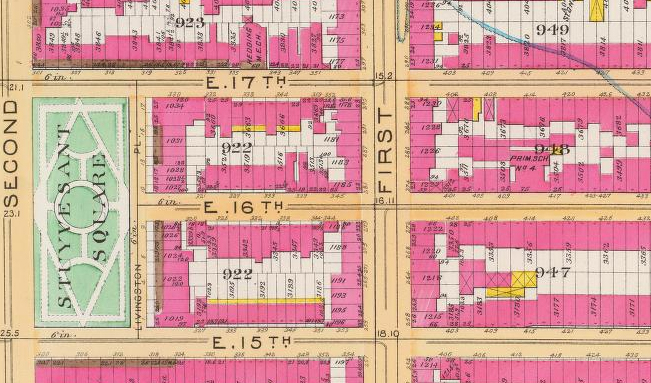

I am pleased to report that two maps of key locations featured in The Angel of Darkness have now been added to the Alienist maps section of the site. As with the maps of key locations featured in The Alienist that I released late last week, the first Angel of Darkness map includes 26 key locations around New York City while the second map includes 15 key locations outside the city. As with the preceding maps, full lists of all the locations marked on the maps can be found below each map, and these can be ordered according to location name, location category, address, or description by clicking on the appropriate column heading. You can also search the list of locations via the search field included immediately below the maps.

In addition, the first 17th Street newsletter has been sent out to subscribers. For those who haven’t signed up and may be interested, the newsletter will be released on a monthly basis to provide a summary of the preceding month’s book and website news, a summary of the topics covered during the preceding month’s history blogs, and an author spotlight section containing an excerpt from an author interview/article that might be of interest to visitors. You can view the July newsletter here. If you think you would be interested in receiving the monthly newsletter, you can sign up via the site’s side menu. Your email address will not be shared with any third parties and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Finally, I thought it might be of interest to visitors that Caleb Carr was recently asked to comment on a long and elaborate New York Times piece from 1852 about a heatwave that hit the city during July of that year. The piece’s unusual length, subject matter, and purplish prose drew varying interpretations from the other eminent historians and writers who were asked to comment on the piece, with Mr. Carr focusing his comments on the attitude expressed by the journalist in the piece.

“The more dramatic he makes it sound, the more he makes himself and his readers feel that they are surviving a great struggle,” Mr. Carr said, “that just by getting through the average day in New York, they are validating what in nearly all cases are anonymous — and all too often, in their own minds, meaningless or at least futile — existences.”

“Maybe life in New York now,” he added, “so clean, so crime-free, so law abiding and safe, is a better place. I don’t know. But personally, I preferred the town that made each citizen feel that kind of validation in mere survival.”

The full article can be read at the New York Times website.