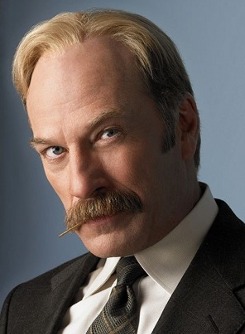

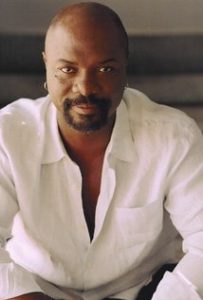

Several new cast members for TNT’s adaptation of The Alienist have been revealed through various sources over the past week. Ted Levine, best known as Captain Stottlemeyer in the TV series Monk, has been cast as former Detective Inspector Thomas Byrnes (at least we know he will be able to pull off the Detective’s famous handlebar moustache!), while Giorgio Spiegelfeld has been cast as Henry Wolff. There is also some indication that Antonio Magro (Blood Orange) may have been cast as Paul Kelly, with audition tape company Shelftape Space congratulating Antonio on his booking. I will update this post if confirmation from another source is provided for this casting.

In addition to casting news, an article on Hungarian website Origo.hu reports that the production team are building a vast replica of old New York north of Budapest for shooting in the coming months! Unfortunately, I do not speak Hungarian but from the photos shared on the article, it appears that the set will be quite monumental in size. Meanwhile, several of the actors who have already been cast, including Luke Evans and Q’orianka Kilcher, have posted photos on their social media accounts indicating that they have arrived in Budapest or will be there soon. It looks like shooting is starting soon!

Photo Credit: Andrew Eccles