A new element of 17th Street that I’m going to be introducing over the coming months are “book blogs” containing short reviews or features about books that readers of Caleb Carr’s work might find interesting or enjoyable. However, rather than starting with my own recommendations or recommendations from site visitors, I thought it might be appropriate to spend the first few months overviewing some of the works Caleb Carr has said were major influences for his work, ranging from Wilkie Collins to Jacob Riis for The Alienist, Jules Verne to H. G. Wells for Killing Time, and Arthur Conan Doyle to H. Rider Haggard for The Legend of Broken.

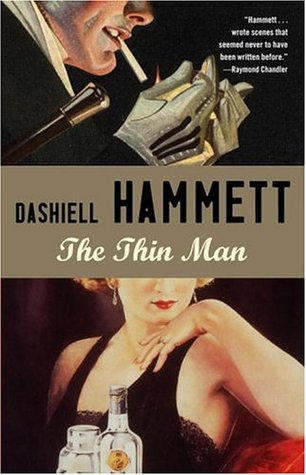

As we’re currently in the middle of the holiday season, I thought that it might be appropriate to start with a Christmas-themed novel that Caleb Carr cited in the NYT web chat earlier this year as “a huge inspiration” for The Alienist, Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man. As always, the following is only one woman’s opinion of the book; if you’ve read the book, I’d love to know what you thought in the comments.

What’s it about?

It’s Christmas in Prohibition era New York City, and former detective Nick Charles, his smart and sassy wife Nora, and their feisty Schnauzer “Asta” have returned to the city in order to escape their San Francisco in-laws for the holiday season. The novel opens with Nick being found by the daughter of an old acquaintance in a speakeasy while he is waiting for Nora to finish her Christmas shopping. It quickly becomes apparent that the acquaintance — a “crazy” inventor — hasn’t been seen in the city for months, his ex-wife and grown-up children are trying to locate him, and his lawyer is suspicious that Nick has been hired by the ex-wife to search for him. But things really heat up when the inventor’s secretary and former lover is found dead in her rooms, her body riddled with bullets.

Under pressure from the inventor’s daughter, the inventor’s lawyer, and the police, Nick finally agrees to join the investigation into the mystery that threatens to disrupt he and Nora’s drinking holiday. For the remainder of the novel, we follow private investigator Nick, who always has a cocktail on hand, into the world of speakeasies, gangsters, petty criminals, and pistols that is 1930s New York City.

My thoughts

The Thin Man is classic hardboiled detective fiction written in 1932 by Dashiell Hammett, a former operative for Pinkerton’s Detective Agency, giving the novel an air of authenticity. Although I found the writing a bit thin in places (oh look, a pun!), that’s to be expected for a short work of this genre, and I’m used to it from other writers of the time period. I will admit that I found it a little irritating to realise at the conclusion of the novel that the reader hadn’t been privy to all the clues throughout the course of the story, but it was ultimately well-plotted enough that I’m willing to forgive it on that particular shortcoming. However, probably my favourite element of the novel — and the thing that kept me reading — was the continual bantering and witty repartee between Nick and Nora, something that reminded me strongly of the amusing exchanges between John and Sara in the Alienist books (it’s one of my favourite elements of those books, too). For example,

She gave me a newspaper and a cup of coffee and said: “Read that.”

I patiently read a paragraph or two, then put the paper down and took a sip of coffee. “Fun’s fun,” I said, “but right now I’d swap you all the interviews with Mayor-elect O’Brien ever printed — and throw in the Indian picture — for a slug of whis-“

“Not that, stupid.” She put a finger on the paper. “That.”

And,

Nick: “Don’t you think a drink would help you to sleep?”

Nora: “No thanks.”

Nick: “Maybe it would if I took one.”

Do those exchanges remind you of anybody? Of course, not being knowledgable about classic film, I was unaware until I looked it up (ah Wikipedia, what would we do without you?) that this kind of bantering between a leading man and his leading lady is a core element of screwball comedy, which we know from interviews Caleb Carr is a fan of, so perhaps The Alienist contains more tips-of-the-hat to that genre and/or works like The Thin Man than I had previously been aware (and perhaps I should make a point of actually watching some). In any case, it certainly made for an enjoyable read regarding the book at hand. And, on a more personal level, the novel had one extra element of enjoyment for me: I grew up with a Mini Schnauzer so I rather appreciated Asta’s regular appearances in every other chapter — and, that’s right, they are not a cross between a Scottie and an Irish Terrier!

Ultimately, I found The Thin Man to be atmospheric, fun, and worth reading if you enjoy classic detective fiction and/or witty barbs traded between a couple of clever characters over cocktails; and it’s certainly an appropriate read for the holiday season. If you haven’t already read it or seen the 1934 film of the same name, why not pick it up during your last minute Christmas shopping or download it on your eReader for a quick and easy read over the holidays?

Whatever you do decide to read this festive season, I hope you have a very Merry Christmas that is a little less eventful than Nick and Nora’s turned out to be.