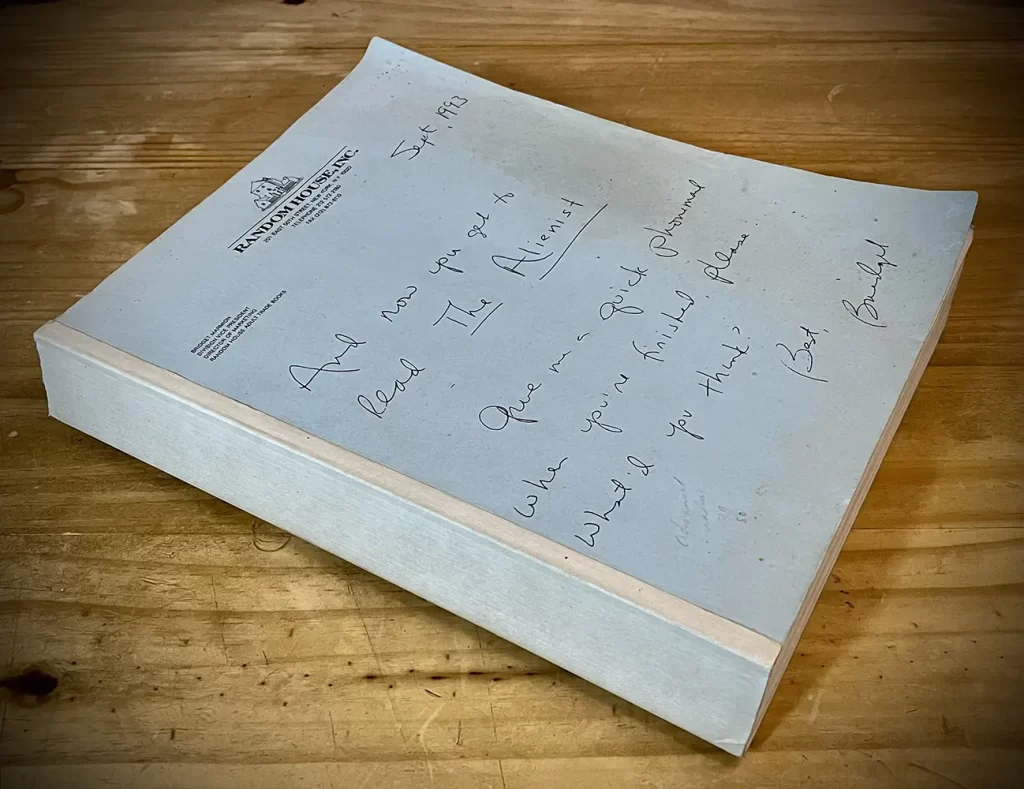

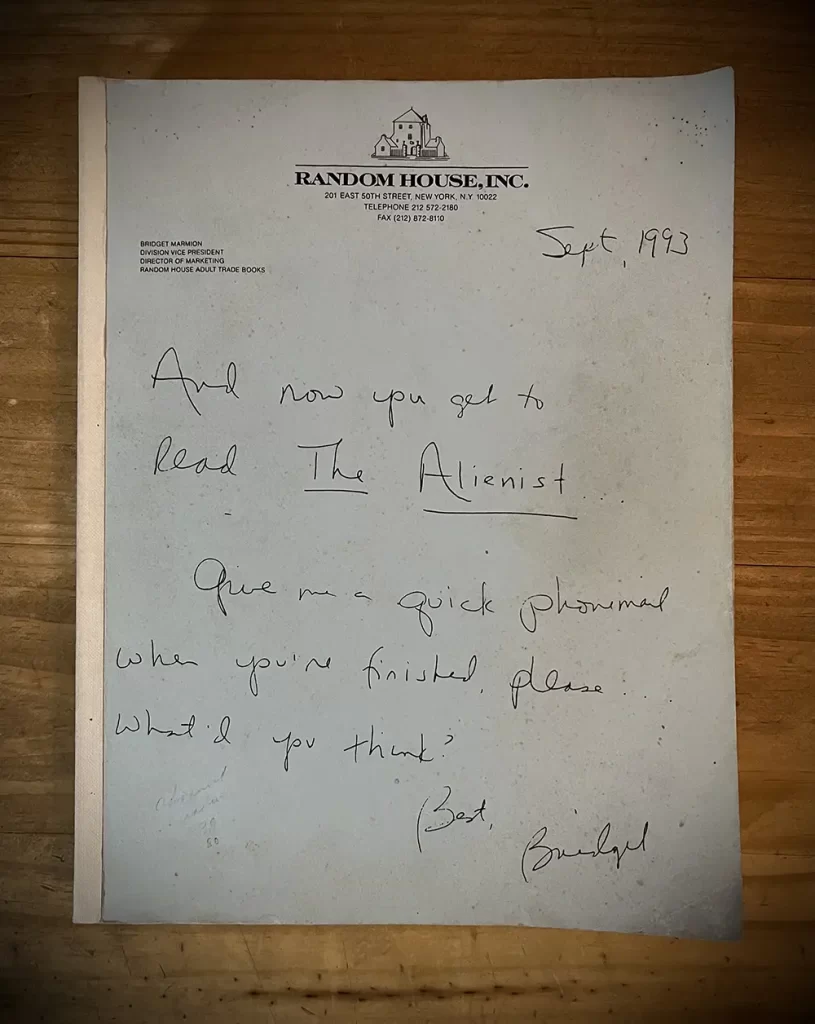

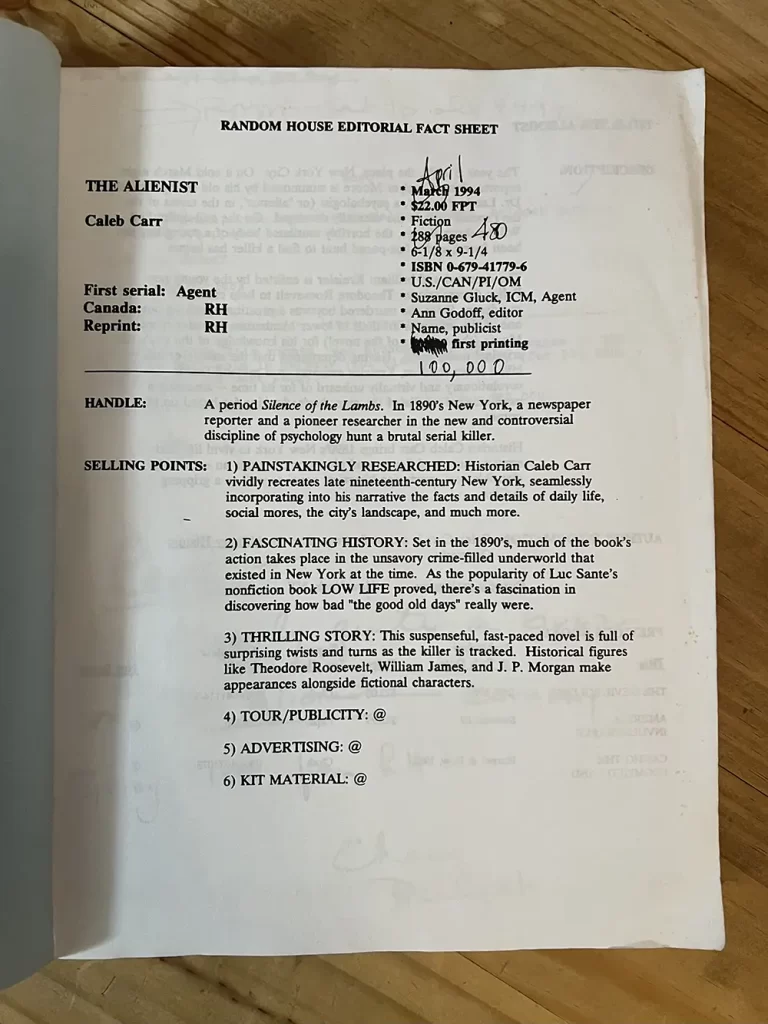

In honor of the 30th anniversary of The Alienist last year, we spent several months tracing the novel’s publication history, along with that of its sequel, The Angel of Darkness. Today, on what would have been Caleb Carr’s 70th birthday, I feel fortunate to be able to share a previously unseen slice of his writing process, generously provided by a member of his family. Ever the meticulous researcher, Caleb revealed in interviews from the ‘90s that in the lead-up to his writing of The Alienist, his research and plot outline was so extensive that it covered the walls of his one-bedroom apartment. In a 1997 interview with Publishers Weekly, it was noted that:

…he devoted “seven to eight months” to “pure research” and plotting. Carr points to a wall of the room. “From the corner of this room all the way across the wall, The Alienist was plotted out on tiny strips of paper.” After an equal amount of time spent writing, he turned in the manuscript.

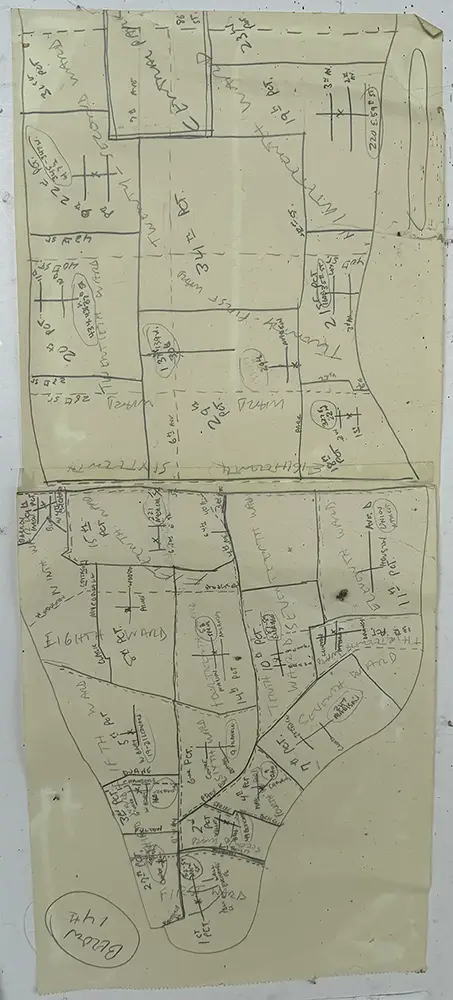

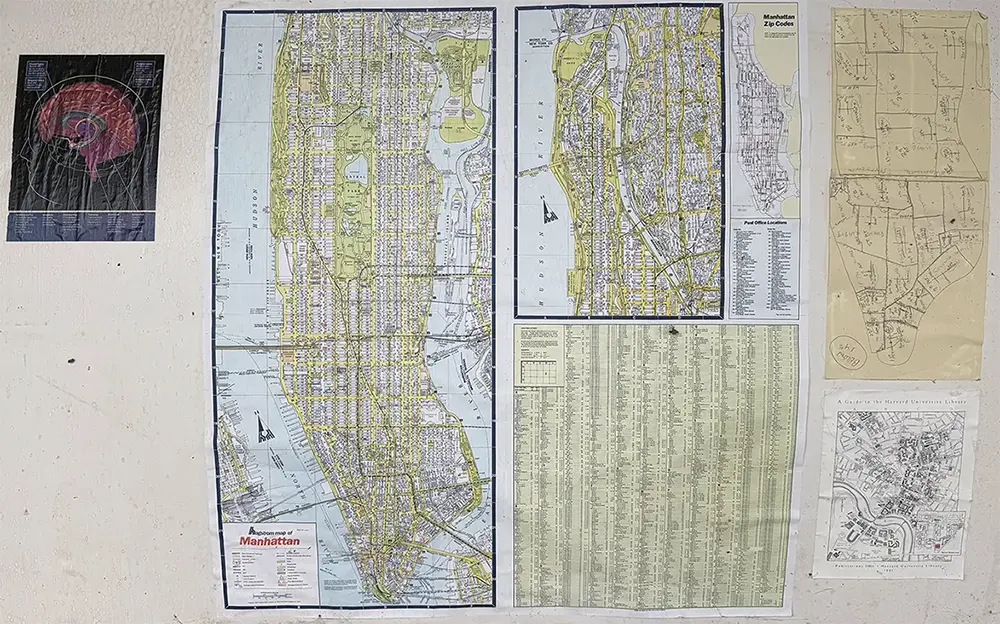

Although the tiny strips of paper have not been found (if they still exist), we can now glimpse a tangible remnant from that time. A large board was recently unearthed containing a poster of the brain, along with several maps directly tied to The Alienist. In today’s post, we will take a closer look at two of these maps—and in doing so, learn more about the real history that shaped Caleb’s vision for The Alienist.

Wards and Police Precincts

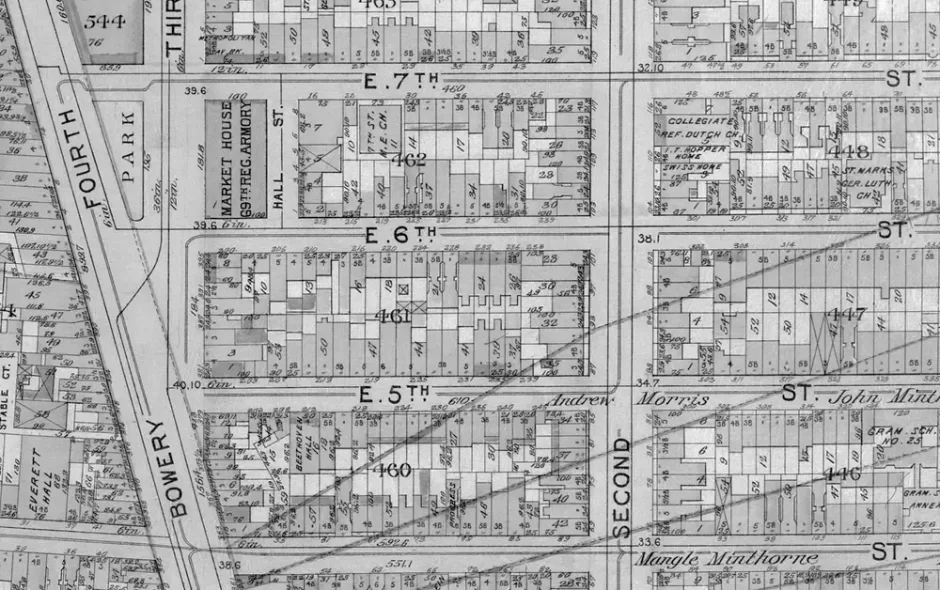

Even though a street map of contemporary Manhattan occupies the largest section of the board, it is the hand-drawn map pinned beside it that offers the greatest insight into Caleb’s research process for the book. Focused on Midtown and Lower Manhattan, the dark pencil lines on this map mark the boundaries of Manhattan’s police precincts from the 1890s. Each precinct is labelled according to its number (e.g., ‘1st Pct.’), and in the middle of each is a star with street intersections corresponding to the precinct’s station house. For example, Caleb has noted that the First Precinct’s station house was located at 52-54 New Street, which is consistent with the station house’s address noted in The Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York.

Readers of The Alienist will remember that police precincts play an important role in the novel. As early as Chapter 2 when John visits the first crime scene, the fact that police from two different precincts were in attendance provided the first clue that the murders under investigation were of a concerning variety:

Near the entrance to the watchtowers atop the anchor, standing under the flimsy light of a few electric bulbs and bearing portable lanterns, were several patrolmen whose small brass insignia marked them as coming from the Thirteenth Precinct (we had passed the station house moments before on Delancey Street). With them was a sergeant from the Fifteenth, a fact that immediately struck me as odd—in two years of covering the criminal beat for the Times, not to mention a childhood in New York, I’d learned that each of the city’s police precincts guarded its terrain jealously. (Indeed, at mid-century the various police factions had openly warred with each other.) For the Thirteenth to have summoned a man from the Fifteenth indicated that something significant was going on.

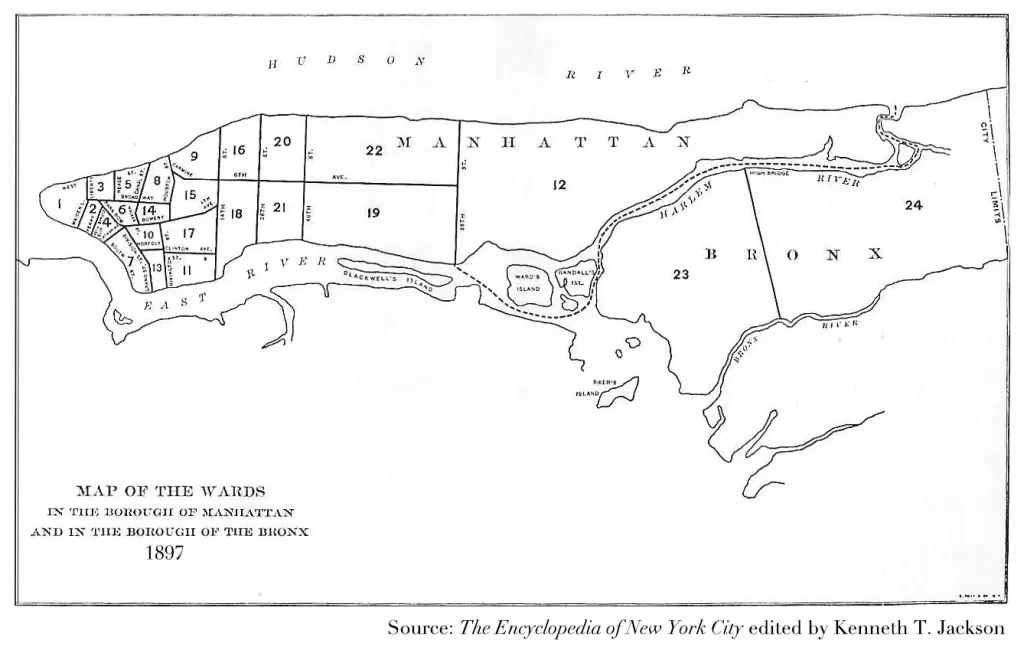

But the precincts aren’t the only focus of the map. A close inspection shows lightly dashed pencil markings atop the precinct boundaries. These markings, which don’t directly match the precincts, correspond to New York’s administrative ‘wards’. From 1686 until the mid-19th century, these subdivisions were the smallest political unit in the city and played a crucial role in local elections. Ward ‘bosses’ (often saloonkeepers) wielded considerable influence, and by the 1850s, the ward system was viewed by reformers as the city’s principal source of corruption.

Even so, this wasn’t the reason Caleb was interested in ward boundaries. By the 1890s, New York’s wards had been replaced with districts for political purposes. Indeed, at this time in the city’s history, the ward system only served two vestigial functions: the administration of public schools (this was centralized in 1896) and the conduct of state and federal censuses. It is the latter of these that caused wards to play a role in The Alienist, and an important one at that.

In Chapter 39, John Moore and Sara Howard pay a visit to Mr. Murray of the Census Bureau to determine whether Beecham, the murderer, may have worked as an enumerator during the 1890 census. While there, the following exchange takes place:

I tried another tack: “I trust he didn’t do anything untoward while he was working in the Thirteenth Ward?”

Murray grunted once. “If he had, I hardly would have promoted him from enumerator to office clerk and kept him on for another five years—” Murray caught himself and jerked his head up. “Just a minute. How did you know he was assigned to the Thirteenth Ward?”

I smiled. “It’s of no consequence. Thank you, Mr. Murray, and good evening.”

Further on in the chapter, John explains:

Enumerators had received their assignments according to congressional districts, which in New York had been subdivided according to wards. My question to Murray about Beecham in the Thirteenth Ward had, I told Sara, been a guess: I knew that Benjamin and Sofia Zweig had lived in that ward, and I was going on the theory that Beecham had met them while working in the area, perhaps even while interviewing their family for the census.

We can see clearly that it was John’s knowledge of the city’s wards and the role they played in the census that led to a breakthrough in the case. One hand-drawn map can therefore tell us much about the novel and Caleb’s process in writing it.

Harvard Campus Map

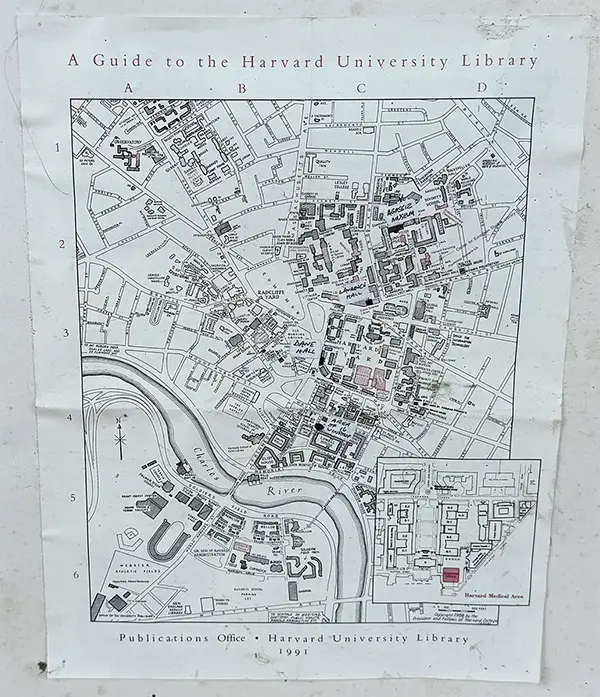

In addition to the precinct map, the other item of interest on the board is a hand labelled map of the Harvard campus. Like the street map next to it, the document is contemporary, but the locations Caleb marked with sticky notes provide a fascinating insight into his outlining and planning process. Of note, most of the locations are not featured in the single flashback scene in The Alienist set at Harvard, so readers may wonder at their significance. To address this, we must first turn back to Chapter 5 in the novel where we learn about the fateful clash that first brought Theodore Roosevelt, Laszlo Kreizler, and John Moore together while they were studying at Harvard in the fall of 1877.

In this scene, we learn that Moore and Roosevelt had, for differing reasons, decided to take a course in comparative anatomy taught by William James, the man who would come to be viewed as the father of modern American psychology but who, at that time, was teaching philosophy and anatomy to undergraduates. At the same time, Kreizler had also been drawn to study with James, but for a different reason. The young Dr. Kreizler had recently completed his medical degree at Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons and was undertaking a new graduate course in psychology offered by James.

Although the youthful Kreizler admired his professor, the two had a fundamental disagreement over a long-standing philosophical debate that still sits at the heart of psychology today, as John explains:

James had been a maudlin, unhealthy boy, and as a young man had more than once contemplated suicide; but he overcame this tendency as a result of reading the works of the French philosopher Renouvier, who taught that a man could, by force of will, overcome all psychic (and many physical) ailments. “My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will!” had been James’s early battle cry, an attitude that continued to dominate his thinking in 1877. Such a philosophy was bound to collide with Kreizler’s developing belief in what he called “context”: the theory that every man’s actions are to a very decisive extent influenced by his early experiences, and that no man’s behavior can be analyzed or affected without knowledge of those experiences.

What started as a battle between the two in the new psychology laboratory James had established in Lawrence Hall eventually led the pair to host a public debate at University Hall, with most of the student body in attendance. Somewhat predictably, the engaging professor won the debate, but this was not the end of Kreizler’s battles that night. Dining with Moore at a tavern across the Charles River, the young Roosevelt approached and engaged Kreizler in an argument that turned personal:

Kreizler laid down the challenge for an affair of honor, and Theodore delightedly took him up, suggesting a boxing match. I knew Laszlo would have preferred fencing foils—with his bad left arm he stood little chance in a ring—but he agreed, in keeping with the code duello, which gave Theodore, as the challenged party, the choice of weapons. To Roosevelt’s credit, when the two men had stripped to their waists in the Hemenway Gymnasium (entered, at that late hour, by way of a set of keys I had won from a custodian in a poker game earlier in the year) and saw Kreizler’s arm, he offered to let him choose some weapon other than fists; but Kreizler was stubborn and proud, and though he was, for the second time in the same evening, predestined for defeat, he put up a far better fight than anyone had expected. His gameness impressed all present and, predictably, won him Roosevelt’s heartfelt admiration.

This richly painted scene established the background needed to bring the three characters back together twenty years later. Yet, if we look closely, the locations featured only included Lawrence Hall, University Hall, the Hemenway Gymnasium, and the unnamed tavern across the Charles River. Of these, only Lawrence Hall is marked on Caleb’s map. What are the other locations, then?

The answer can be found in biographies of Theodore Roosevelt. In the youthful Roosevelt’s freshman year at college, he lived in Mrs. Richardson’s boarding house at 16 Winthrop Street, one of the locations marked on the map. Similarly, the Agassiz Museum, otherwise known as the Museum of Comparative Zoology, was one the young man’s haunts in his junior and senior years. The significance of Dane Hall is a little more difficult to establish, but perhaps the solution lies in the fact that it was only a short distance from the Hemenway Gymnasium where the fateful boxing match in the novel takes place.

Although we can never know for certain, it appears as though this map was annotated before the scene at Harvard was plotted. And it seems likely from the locations marked that Caleb worked backwards from Roosevelt’s time at the college to plan the scene. Perhaps his original ideas included 16 Winthrop Street or the Agassiz Museum, or perhaps he was merely working out relative distances.

In any case, like the precinct map, it provides an intriguing insight into his process. I hope readers found this sneak peek behind the scenes of The Alienist as interesting as I did researching it. Happy Birthday, Caleb. You are missed.