On this final day of the year, it seems fitting to conclude our celebration of The Italian Secretary by harkening back to the origins of 17th Street itself. When this website was opened on December 31 of 2005, I could scarcely imagine the impact it would have on me personally and, more broadly, on Caleb Carr’s loyal readership over the years that were to follow. What started as a way to pay homage to an author and a book series that had touched the lives of so many — the Alienist novels — quickly turned into something far richer and more enduring than I ever anticipated: a space for readers to come together to reflect, imagine, and discover hidden layers in Caleb’s works that will keep them alive long into the future.

In this spirit, I thought it would be enjoyable to close this anniversary series by bringing Caleb’s own brilliant creation, the enigmatic Dr. Laszlo Kreizler, together with Holmes to address the question posed in The Italian Secretary’s afterword: What would have happened had Caleb let the worlds of Holmes and Kreizler collide? As Charles Finch noted in his USA Today review of Surrender, New York: “…every word of fiction Carr has produced seems to have been written in either direct or indirect conversation with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.” This is no accident, particularly as it pertains to the Alienist novels. In the essay Caleb contributed to Ghosts in Baker Street in 2006 (in lieu of the story that turned into The Italian Secretary), he explained his motivation in some depth:

“In attempting to bring to life a late nineteenth-century psychologist who becomes his own form of ‘amateur detective,’ I intended to pay homage to, and recognize the works of, all the forensic and consulting psychologists that Conan Doyle so carefully failed to mention in his own works. But at the same time, I had no desire to reinvent Sherlock Holmes, even in a veiled form, nor would mine be an attempt to demonstrate any shortcomings of the great detective’s character, or that of his creator’s. Rather (at least ideally), the two fictional creations and intellectual approaches would be complementary, not contradictory, for one can pay homage far more effectively by filling some of the available creative space around a beloved character than by trying to crowd the same territory through imitation or reinvention.”

Caleb further elaborated on his decision to focus on the work of early psychologists in the interview he gave to The Sherlock Holmes Companion in 2009. Clarifying that “the idea of the Alienist was really to create a character to solve all the cases Sherlock Holmes could not solve,” he pointed out that there was “a whole category of crimes — stranger-based crimes — that have no evidence trail. If you ignore motivation and profiling, they will remain unsolved forever.” Conan Doyle avoided addressing this class of crime in the Holmes stories as he wanted to demonstrate the use of reason to solve crime purely on the basis of physical evidence; but it was these stranger-based crimes that became the foundation for the Alienist books.

By considering the respective motivations of the authors involved, we get our first clue of what might have happened had Caleb brought Holmes and Kreizler together on a case. With this in mind, let us now turn back to The Italian Secretary’s afterword to explore the ideas presented there about what such a meeting might have entailed and what its outcome might have been.

“Dr. Kreizler, Mr. Sherlock Holmes…”

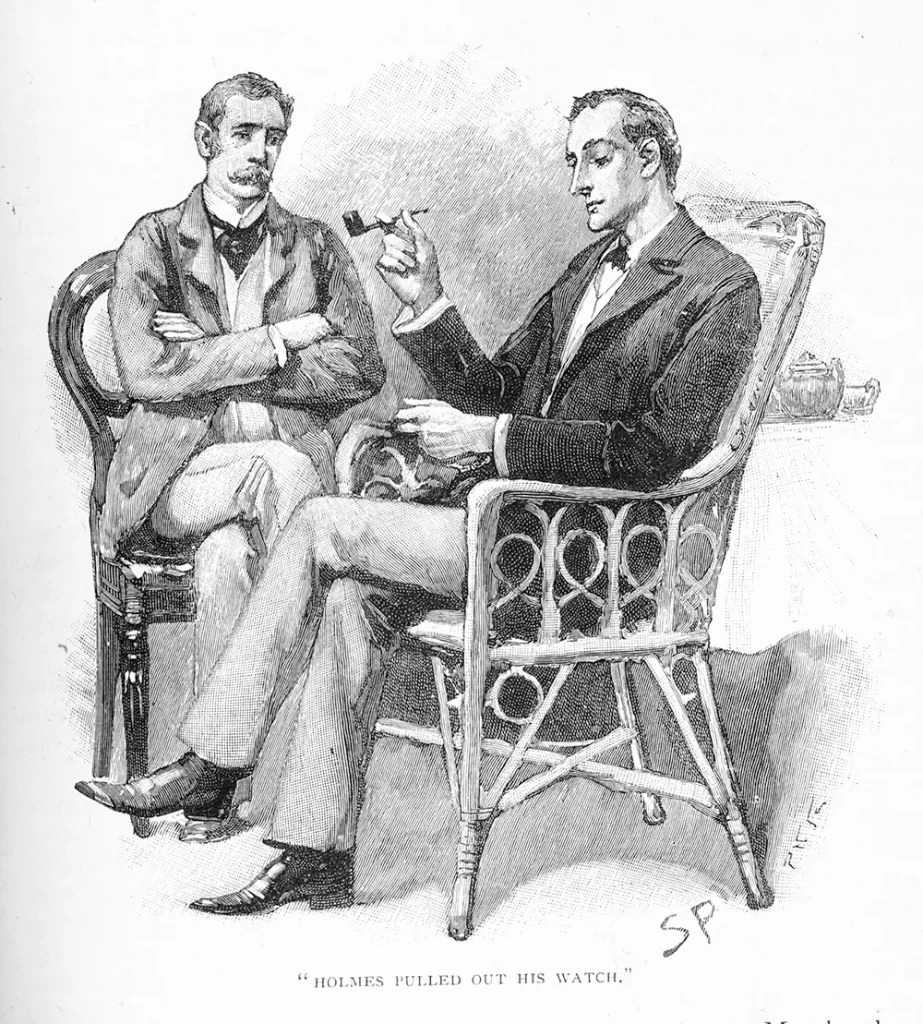

“Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” said Stamford, introducing us.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

“How are you?” he said cordially, gripping my hand with a strength for which I should hardly have given him credit. “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.”

“How on earth did you know that?” I asked in astonishment.

“Never mind,” said he, chuckling to himself.

As Jon Lellenberg, the U.S. Representative to the Conan Doyle Estate, points out in the opening of The Italian Secretary’s afterword, perhaps the most famous and fated introduction in the whole of English literature occurs in A Study in Scarlet when Dr. John H. Watson meets the great consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes. Each in need of a fellow lodger to split the rent, they are introduced at the chemistry laboratory of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital by Watson’s former surgeon’s assistant, Stamford. It was a meeting that resulted in a crime-solving partnership that has never been equaled in modern detective fiction, spanning several decades, four novels, and fifty-six short stories. But what would have happened if the meeting had gone a different way?

The first alternative Lellenberg contemplates in his essay is a meeting between Dr. Watson and Dr. Kreizler; however, he ultimately concludes that the lack of tension between the two — both medical men who, despite differing specialties, agreed that the mind is shaped by biological and environmental factors — would not have resulted in a particularly effective partnership, at least as far as solving crime is concerned. Indeed, the pairing may more closely have resembled the extant relationship between Dr. Kreizler and Lucius Isaacson, who had medical training as rigorous as Watson’s, though with a far greater knowledge of forensics. While Kreizler and Lucius work well together, as a contained crime-solving duo, one could argue that they are not best placed to augment each other’s limitations, which is why a team of investigators is needed in the Alienist novels. One must turn away from Watson, then, if one is to bridge the worlds of Conan Doyle and Caleb Carr.

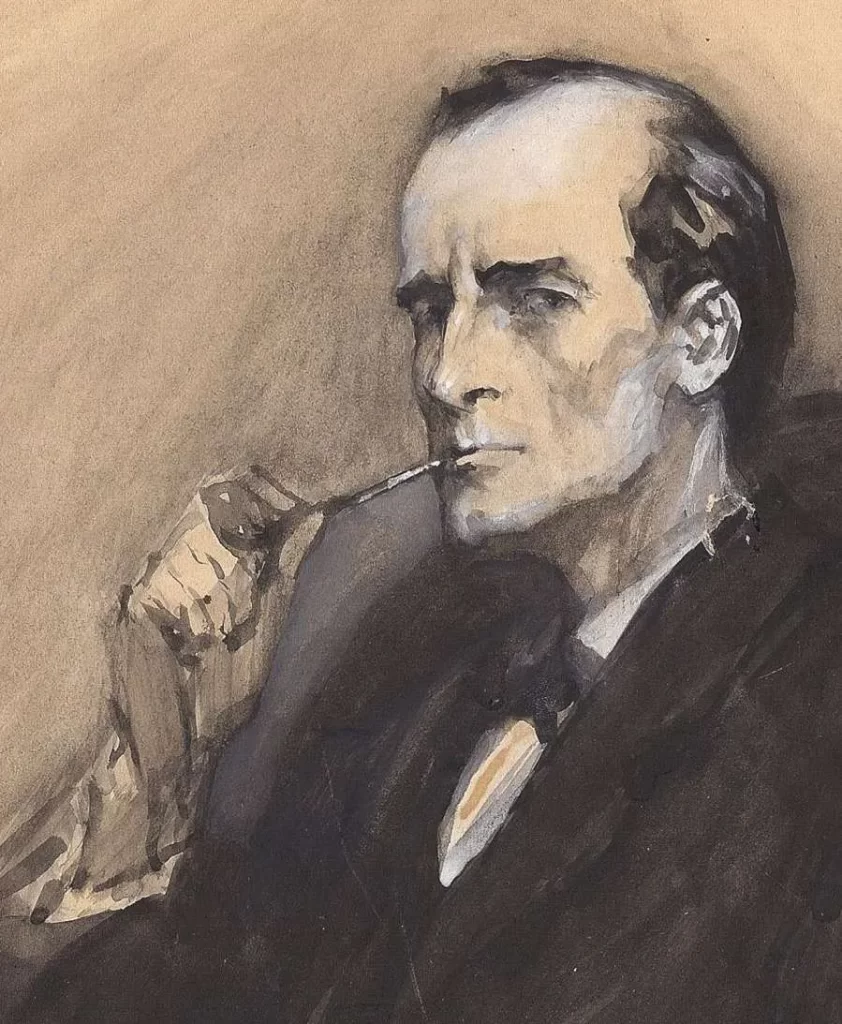

The meeting Lellenberg prefers to imagine is one that would have resulted in far greater tension: that between Dr. Kreizler and Sherlock Holmes himself. From their very introduction, the pair would undoubtedly have sized each other up and come to mutually wary conclusions about the other’s method. While Kreizler, always open to eccentric characters (as Stevie noted in The Angel of Darkness), would have been intrigued by Holmes’s powers of observation and deduction, Lellenberg correctly notes that he would also have grown “impatient with its limitations.” Holmes, on the other hand, would likely have been suspicious of the doctor’s emphasis on psychological context, for, as he once warned Watson in A Scandal in Bohemia, “It is a capital mistake to theorize before one has data. Insensibly one begins to twist facts to suit theories, instead of theories to suit facts.” Yet, despite this, Lellenberg doesn’t see this tension as problematic; rather, the two men’s contrasting approaches may have been the very fuel that would have propelled an investigation forward:

…the desire to see the two approaches — Holmes’s and Kreizler’s — collide with each other cannot be gainsaid. We must be dialecticians ourselves if we are to give both approaches their just due. Whether a collaboration would be set in London or New York at the end of the nineteenth century is immaterial — both of those great metropolises offer fertile ground for a case that would challenge each of these men, and make for a partnership profoundly upsetting to both, but tremendously interesting to the reader. Sparks would fly, and it is easy to imagine Watson and Moore quietly retiring to one of their clubs every so often to get away from the scene and commiserate together. But the temptation is there. I hope Mr. Carr succumbs to it eventually.

The Italian Secretary, Afterword

Unfortunately, when Caleb was asked in an interview with The Age whether he was ever likely to succumb to the temptation, he was not enthusiastic. “That’s not my fictional style,” he explained. “I’m known for incorporating real historical characters into my books. It’s far more likely that Conan Doyle, rather than Holmes, would appear in a Kreizler tale.” Although this may have disappointed readers keen to see the first consulting detective collaborate with the first forensic psychologist, Caleb’s instinct was a perceptive one, particularly given his motivation regarding the Alienist novels themselves. After all, Kreizler was not interested in brilliant minds for their own sake; he was interested in the psychological contexts that shaped them. In this light, Conan Doyle himself — rather than his creation — may have been the most compelling subject for a Kreizler inquiry.

“Dr. Kreizler, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle…”

“Do not,” Kreizler answered slowly, trying very hard to be clear, “look for causes in this city. Nor in recent circumstances, nor in recent events. The creature you seek was created long ago. Perhaps in his infancy — certainly in childhood. And not necessarily here.”

The Alienist, Chapter 6

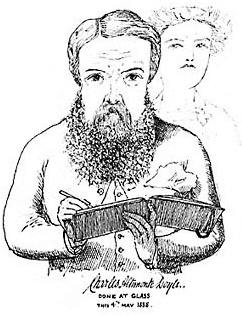

The year 1893 was a momentous one for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. On October 10, the newly famous author’s father, Charles Altamont Doyle, died suddenly at the age of 61 from what was described as “a fit during the night” while confined at the Crichton Royal Institution in Dumfries, Scotland. An illustrator and watercolorist who had once exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy, Charles Doyle had spent much of the previous decade at Sunnyside, the Montrose Royal Lunatic Asylum, after struggling with depression and alcoholism. In later years, his dependence on alcohol was compounded by epileptic seizures and episodes of memory loss.

This alone would have been a tragic set of circumstances. However, just two months after Charles Doyle’s death, in December of the same year, his son added to them by making the unthinkable decision to kill off his most famous creation — a character who also was no stranger to addiction, as we see in the opening paragraphs of The Sign of Four, published in 1890:

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantel-piece and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long, white, nervous fingers he adjusted the delicate needle, and rolled back his left shirt-cuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoughtfully upon the sinewy forearm and wrist all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-marks. Finally he thrust the sharp point home, pressed down the tiny piston, and sank back into the velvet-lined arm-chair with a long sigh of satisfaction.

The Sign of Four, Chapter 1

Three times a day for many months I had witnessed this performance, but custom had not reconciled my mind to it. On the contrary, from day to day I had become more irritable at the sight, and my conscience swelled nightly within me at the thought that I had lacked the courage to protest. Again and again I had registered a vow that I should deliver my soul upon the subject, but there was that in the cool, nonchalant air of my companion which made him the last man with whom one would care to take anything approaching to a liberty. His great powers, his masterly manner, and the experience which I had had of his many extraordinary qualities, all made me diffident and backward in crossing him.

Yet upon that afternoon, whether it was the Beaune which I had taken with my lunch, or the additional exasperation produced by the extreme deliberation of his manner, I suddenly felt that I could hold out no longer.

“Which is it to-day?” I asked,—“morphine or cocaine?”

He raised his eyes languidly from the old black-letter volume which he had opened. “It is cocaine,” he said,—“a seven-per-cent. solution. Would you care to try it?”

Although Conan Doyle would eventually resurrect his great detective, the events of 1893 invite a more searching question, one that Dr. Kreizler, with his insistence that “the answers one gives to life’s crucial questions are never truly spontaneous,” would surely have asked. Of course, Conan Doyle always insisted that the hyperrational Holmes — far removed in temperament from his troubled, artistic father — was largely inspired by another important figure in his life, Dr. Joseph Bell, for whom he had clerked at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; but it is noteworthy that Bell himself rejected the idea, writing to his former clerk, “You are yourself Sherlock Holmes and well you know it.”

It is curious to consider what Dr. Kreizler would have made of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. As we saw in Part One, Caleb was deeply sympathetic to the creator of Holmes, particularly in relation to the author’s struggles with grief. And perhaps it is this that would have offered the most likely opportunity to bring the author into Kreizler’s orbit, had Caleb decided to go down such a path. There were, after all, only limited opportunities for the two to have credibly crossed paths, as Conan Doyle visited New York a mere handful of times: once in 1894 — which would have required a prequel to the Alienist novels — or later, between 1922 and 1923, when he was on his speaking tour devoted to spiritualism.

I favor the latter as the more compelling opportunity for Caleb to have brought the two together. By the early 1920s, an aging Kreizler would have been facing his own reckoning with grief as Stevie’s health declined, forcing him to confront the limits of intellect and reason in the face of loss. Conan Doyle, too, arrived in New York in 1922 carrying the heavy weight of bereavement. Although he had turned to spiritualism prior to the Great War, the deaths of his son Kingsley, his brother Innes, and other close family members during this time only strengthened his commitment to his metaphysical beliefs.

While it is, of course, Caleb alone who could have best brought these characters together, one can nonetheless imagine a scenario in which the world-famous author might have found his way to the door of 283 East Seventeenth Street with an unsettling case only Dr. Kreizler and his team could hope to address. For my own part, I think it would have been fascinating to see how these characters — now aging, reflective, and increasingly aware of mortality — might have applied their respective approaches in the altered intellectual and social landscape of New York in the 1920s. Such a meeting, had it occurred, could have proved revealing on all sides.

Alas, we must leave such imaginings where they belong: in the realm of speculation. For whatever reason, the meeting between Kreizler and Conan Doyle was never written, but the fact that it feels so tantalizingly possible speaks to the care with which Caleb shaped his fictional worlds, all of which were deeply rooted in history, psychology, and moral inquiry. As we end The Italian Secretary’s anniversary series, and 17th Street enters its third decade, it feels appropriate to simply be thankful that we have been left with such a treasure-trove of richly imagined works that they still invite analysis and reflection this many years on.