For those who are finding the website through this post, please note that Caleb Carr passed away in May, 2024. See Remembering Caleb Carr (1955-2024) for 17th Street’s memorial to a beloved author.

“You can practically hear the clip-clop of horses’ hooves echoing down old Broadway … You can taste the good food at Delmonico’s. You can smell the fear in the air.”

So began The New York Times’s review of The Alienist in 1994, and the words are no less true now than they were then. Published thirty years ago this month on March 15, 1994, Caleb Carr’s breakthrough thriller went on to garner significant public and critical acclaim, spending 24 weeks on the Times’s hardcover fiction bestseller list and earning its author an Anthony Award in 1995. It’s little wonder why. Through its seamless blend of meticulously researched historical detail, captivating team of investigators led by the enigmatic and brilliant Dr. Laszlo Kreizler, and thrilling chase for a killer, the novel captured the imaginations of so many readers that it has been studied in schools and is considered a modern classic of its genre.

For the 20th anniversary of the The Alienist’s publication in 2014, 17th Street featured an in-depth collection of posts exploring the novel’s themes and enduring appeal. This year, we will be commemorating Caleb and celebrating the work’s 30th anniversary by delving into the novel’s journey to publication with some wonderful insights into rare early editions, along with discussing the reception the novel received upon release and the legacy it has left on the genre today. Like the 20th anniversary series, this celebration will take place over a series of posts, and I hope it will provide something of interest to new and old fans alike.

To the beginning, then!

The journey to publication

In the afterword to the 2006 trade paperback edition of The Alienist, Caleb Carr wrote: “Like most wonderful and terrible things, The Alienist was never supposed to happen.”

Two years before the groundbreaking thriller was set to make its appearance and change the landscape of historical fiction, Caleb’s first major sole-authored work of military history, The Devil Soldier, had just been published by Random House, and its author was on the hunt for his next subject. But instead of a work of history, another idea had been brewing. “A lifelong interest in crime and the formation of the mind had led me to decide on a psychological thriller,” Caleb explained in the 2006 afterword, “but my grounding in nonfiction would not allow me to be anything but rigorous in my research and approach. This, I soon realized, could get tricky: How do you devise a story that includes the kind of hard science I’d nosed around in without making readers and audiences want to drive ice picks through their own eyes?”

The challenge went beyond the difficulties of incorporating complex philosophical ideas and early forensic science in a thriller, though. Given that Caleb was still in the process of building a profile as a serious historian, his agent, Suzanne Gluck at WME, and editor, Ann Godoff at Random House, were not of a mind to encourage Caleb’s move from nonfiction to fiction. Thus, once he settled on a subject — inspired, at least in part, by his experiences as a college student during the ‘Son of Sam’ killings in New York — Caleb needed a way to convince his publishing partners to support the switch. The solution, he decided, lay in selling the story as a work of nonfiction, not fiction. To pull off such a scheme required not only a believable premise, but also doctored paperwork, including a false visual: a photograph showing Dr. Laszlo Kreizler visiting Theodore Roosevelt in the White House, years after the events of The Alienist supposedly took place.

The process of creating the false image, and the a copy of the photograph itself, can be found in the 2006 afterword (which I highly recommend reading), but for our purposes here, what matters is the end result: it worked. Caleb’s agent, Suzanne Gluck, took the ruse well, and his editor, Ann Godoff — even then, a formidable force in publishing — was also won over. And so, after receiving an advance of $65,000 for the book, the process of writing began. In an interview with New York Magazine in 1994, it was explained:

For fourteen months, Carr lived The Alienist. He read dozens of books on serial killers and huddled with Dr. David Abrahamsen, a dean of forensic psychiatry. Friends would bump into Carr at odd hours, in odd parts of town, trying to track down addresses that had long disappeared. One ex-girlfriend recalls that during touch-football games, he’d talk brain dissection.

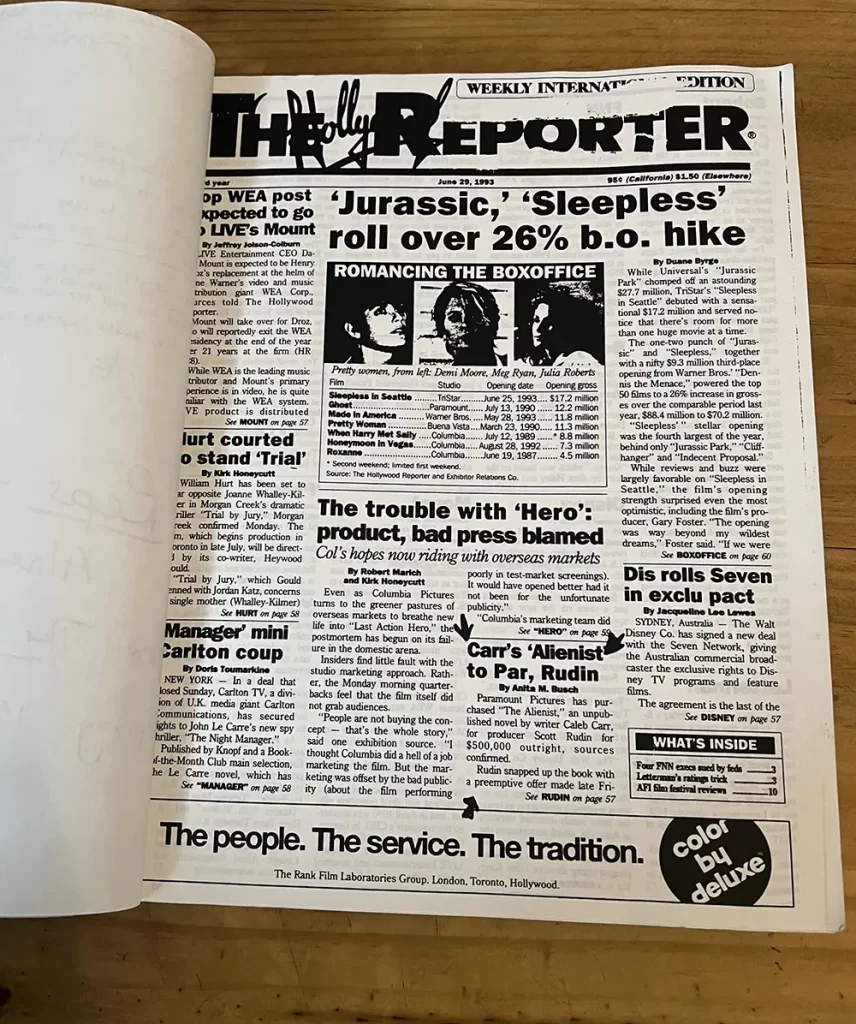

The specifics of the novel’s editorial process have not been discussed in interviews (at least to my knowledge), but the novel’s timeline from Spring, 1993 onward is known. At that time, Caleb turned in the 700-page manuscript, and soon afterward it began to circulate around Hollywood. By late June, the debut thriller had built such buzz that producer Scott Rudin had purchased the film rights for $500,000. This only caused interest in the still-unpublished novel to skyrocket.

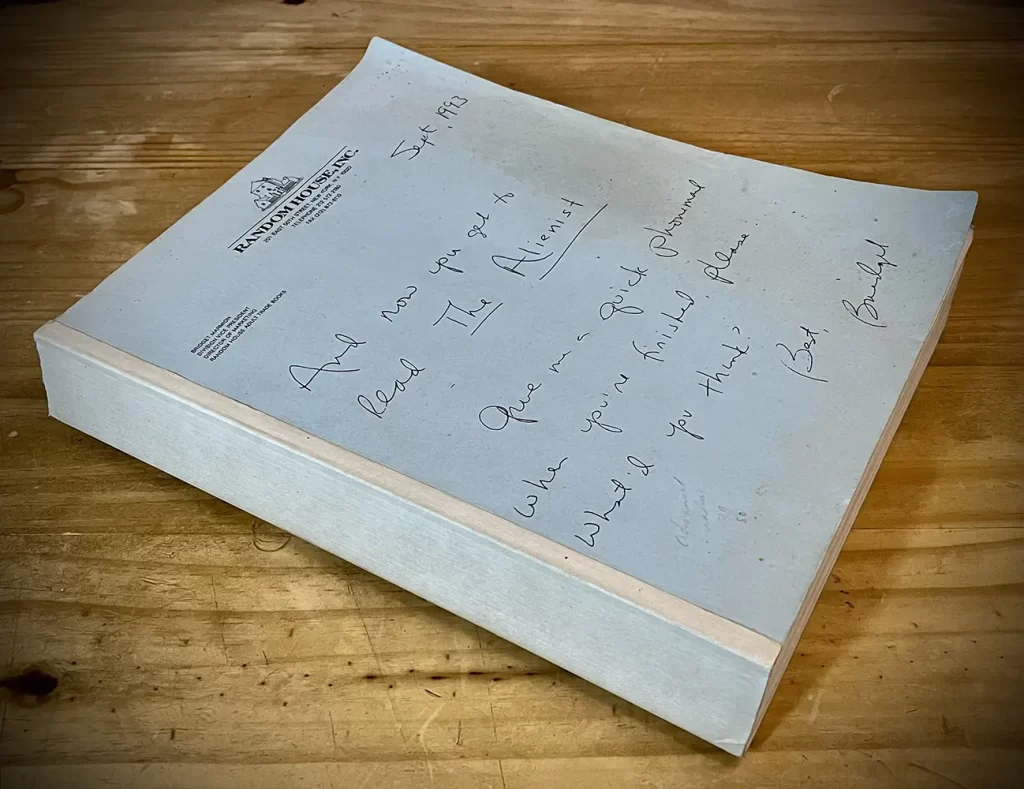

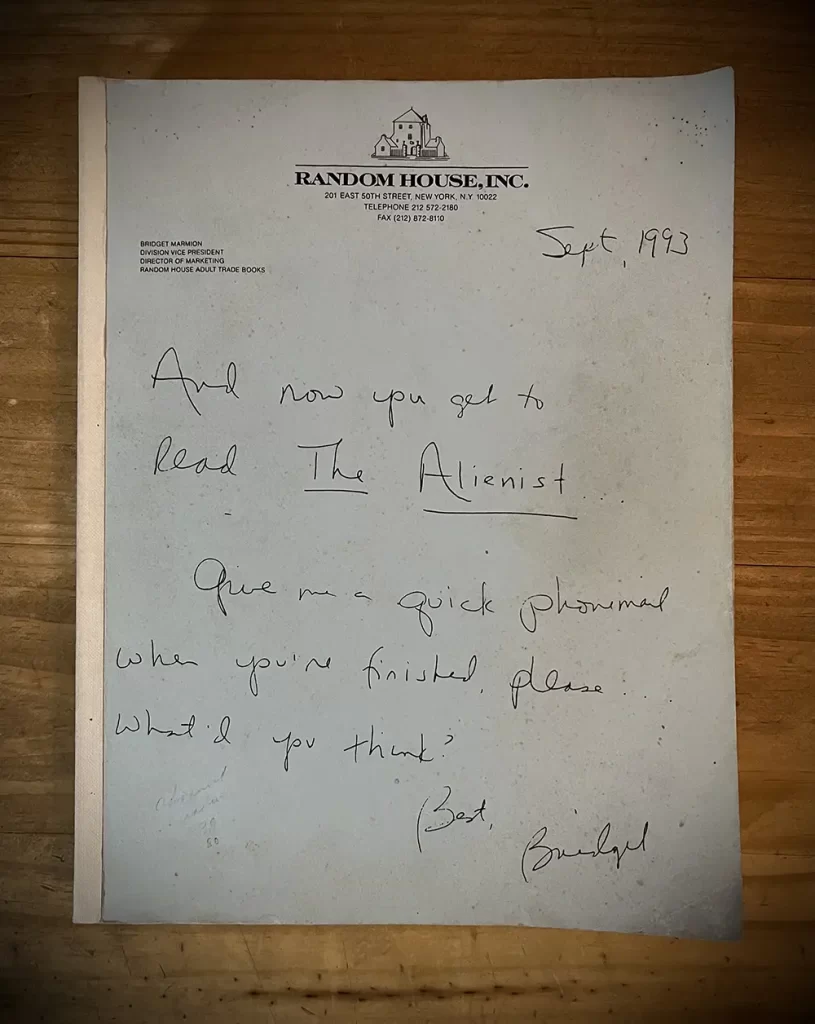

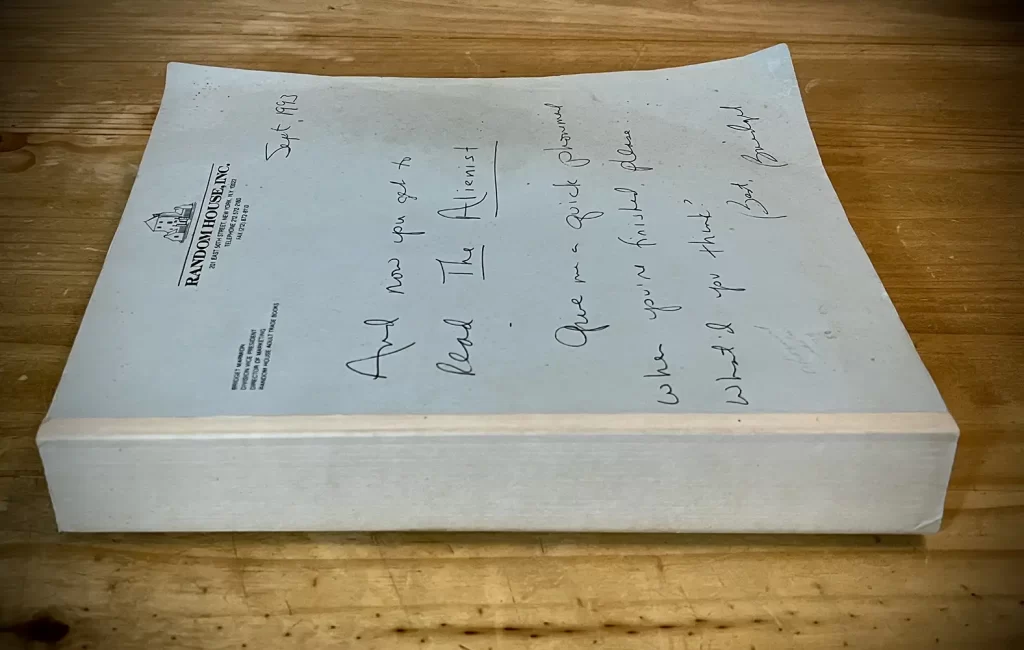

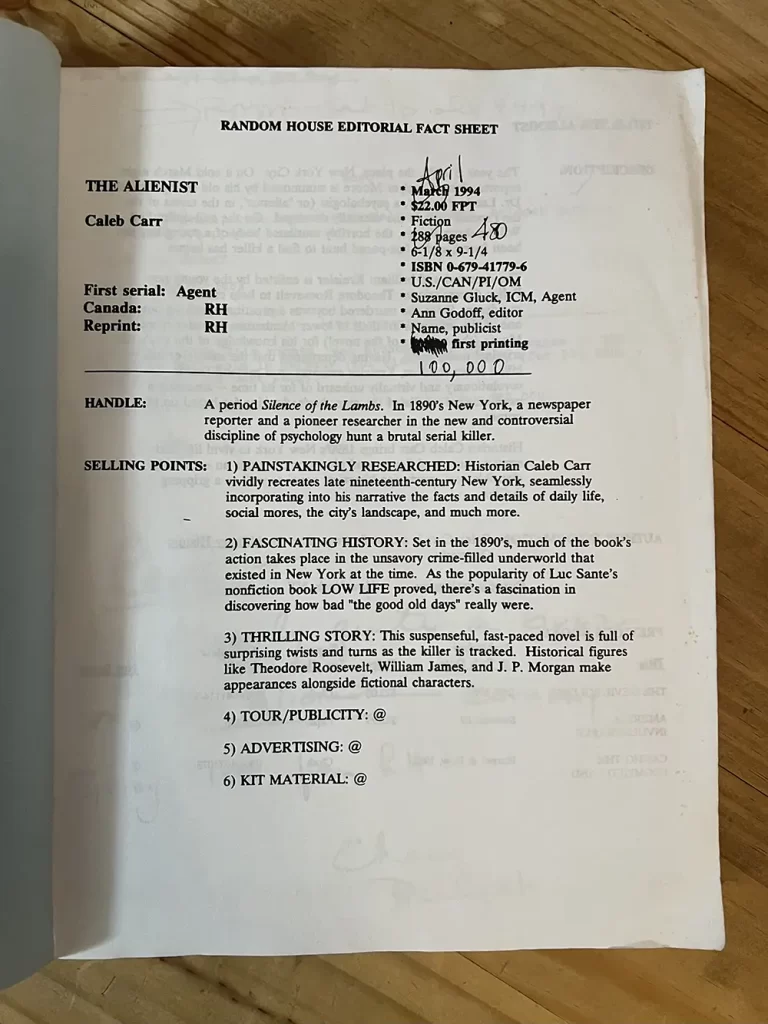

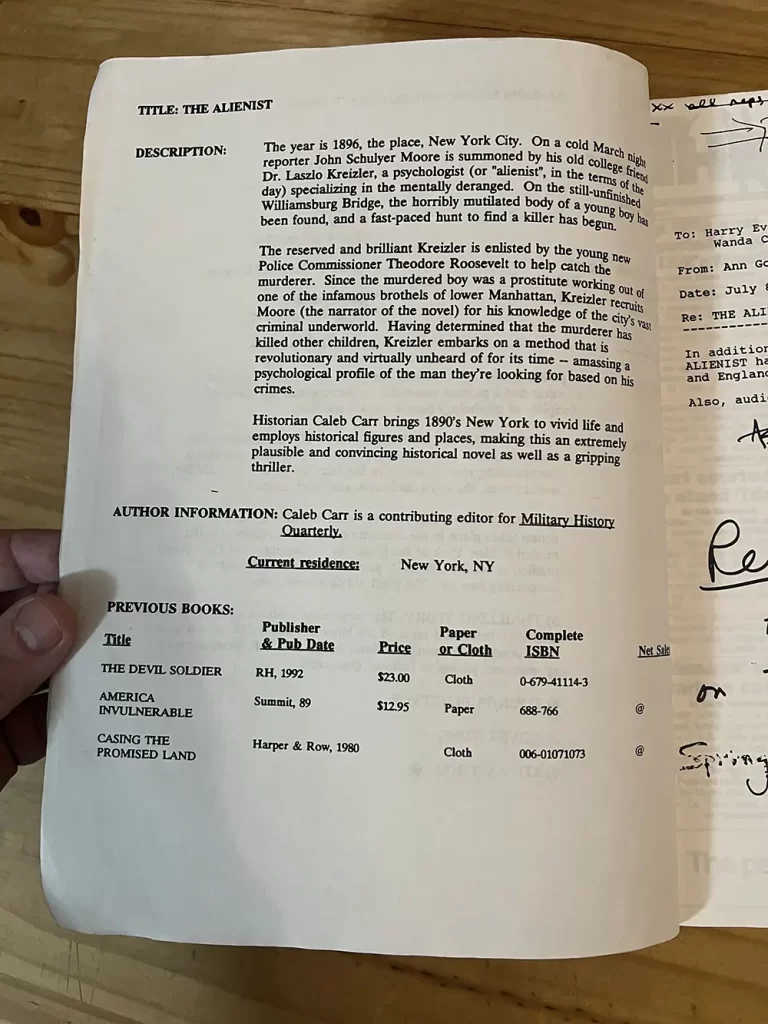

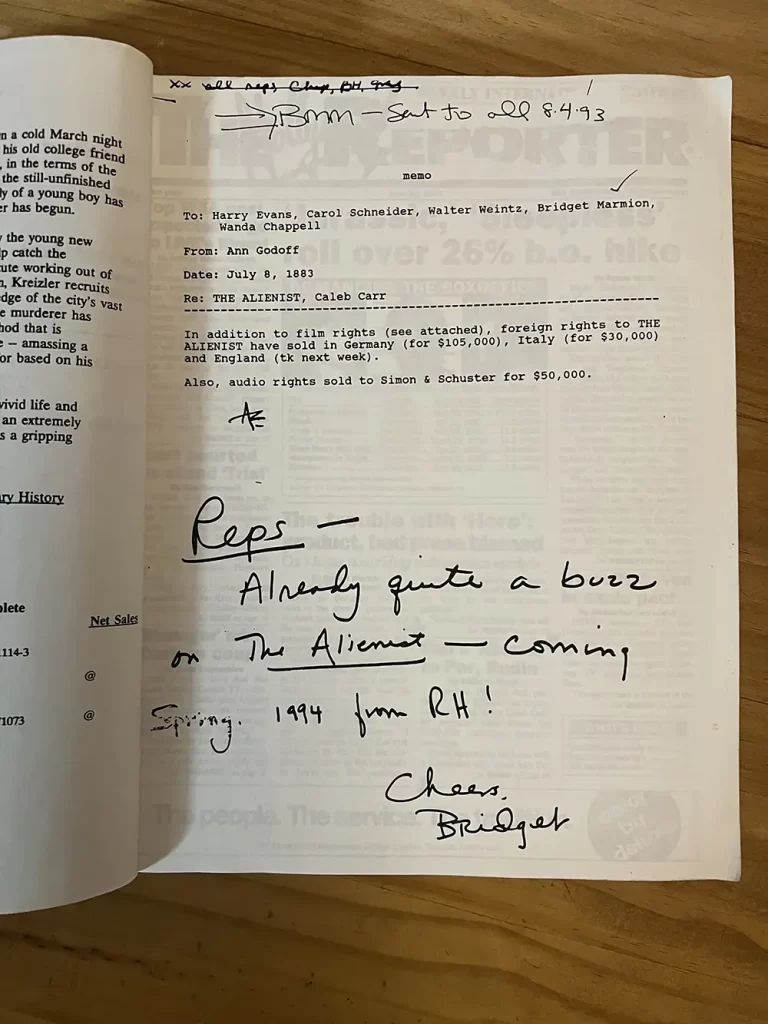

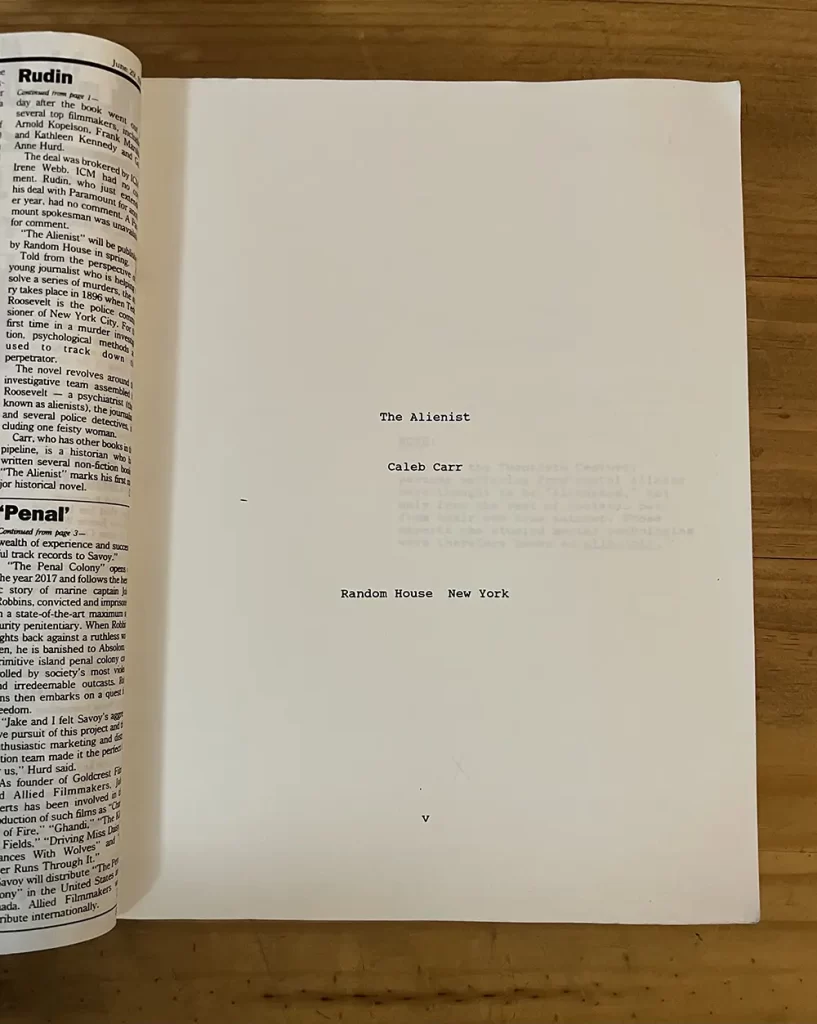

By September of 1993, photocopied typescripts of the novel were ready to be distributed to sales representatives. A kind visitor to 17th Street, Steve Rogers, sent through photographs of an extremely rare copy of one of these typescripts that he was recently able to acquire. Bound in plain blue stock paper and tape with a note from Bridget Marmion, the Random House Director of Marketing, on the cover, this fascinating typescript includes an editorial fact sheet (revealing a first printing of 100,000 copies), a copy of The Hollywood Reporter‘s article on Scott Rudin’s purchase of the film rights, and the manuscript itself.

To a collector, this is like finding gold. Other than Caleb Carr’s original manuscript, editorial copies, and whatever copies were distributed to sell the movie rights, this is likely the earliest copy that exists. But Steve had several other rare editions that he was kind enough to share photographs of for the website.

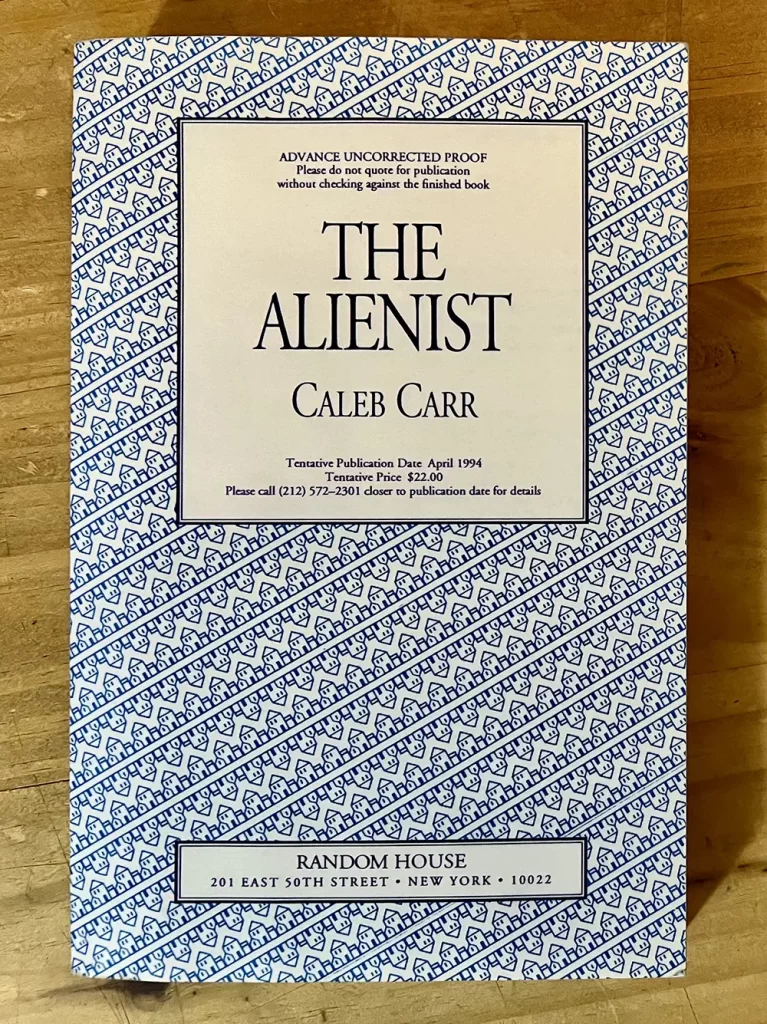

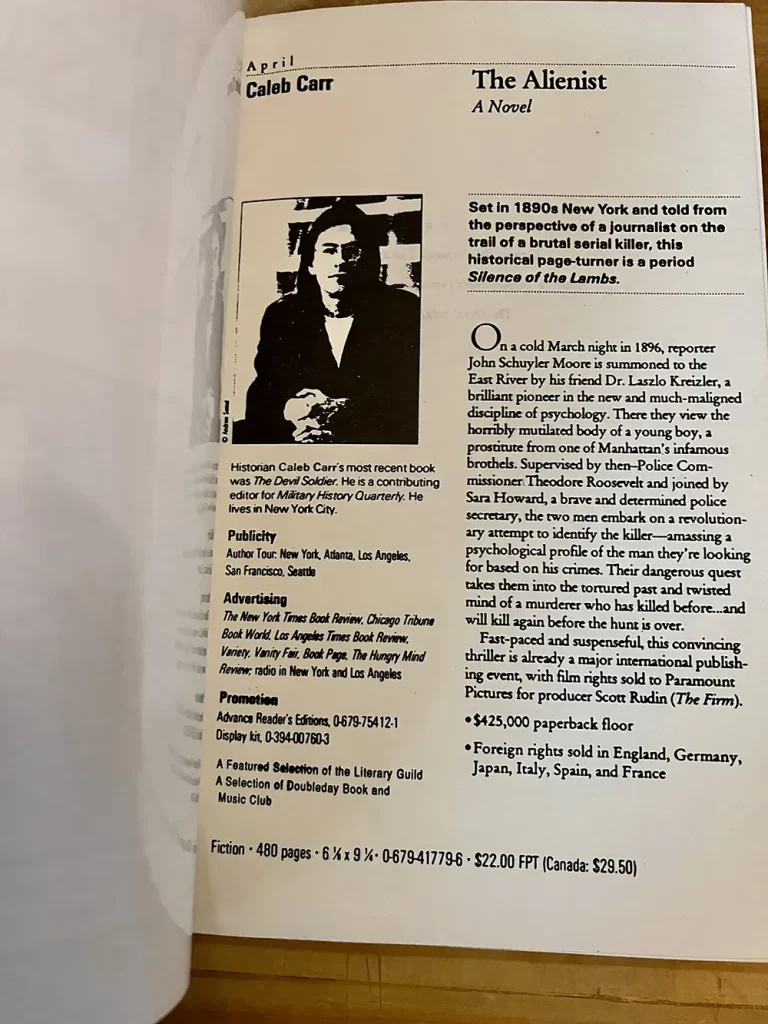

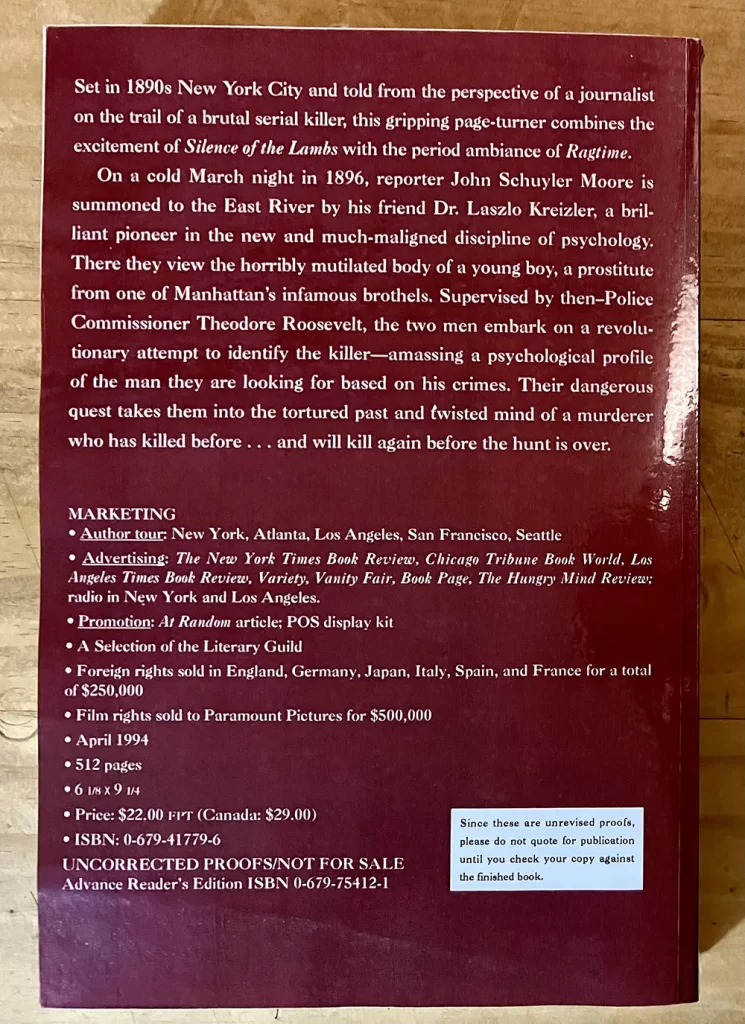

In the lead up to the novel’s release, uncorrected proofs were distributed to reviewers, critics, and industry professionals for early evaluation and feedback to generate interest. The Alienist‘s uncorrected proof edition had a standard blue and white Random House paperback binding, with promotional material on the flyleaf.

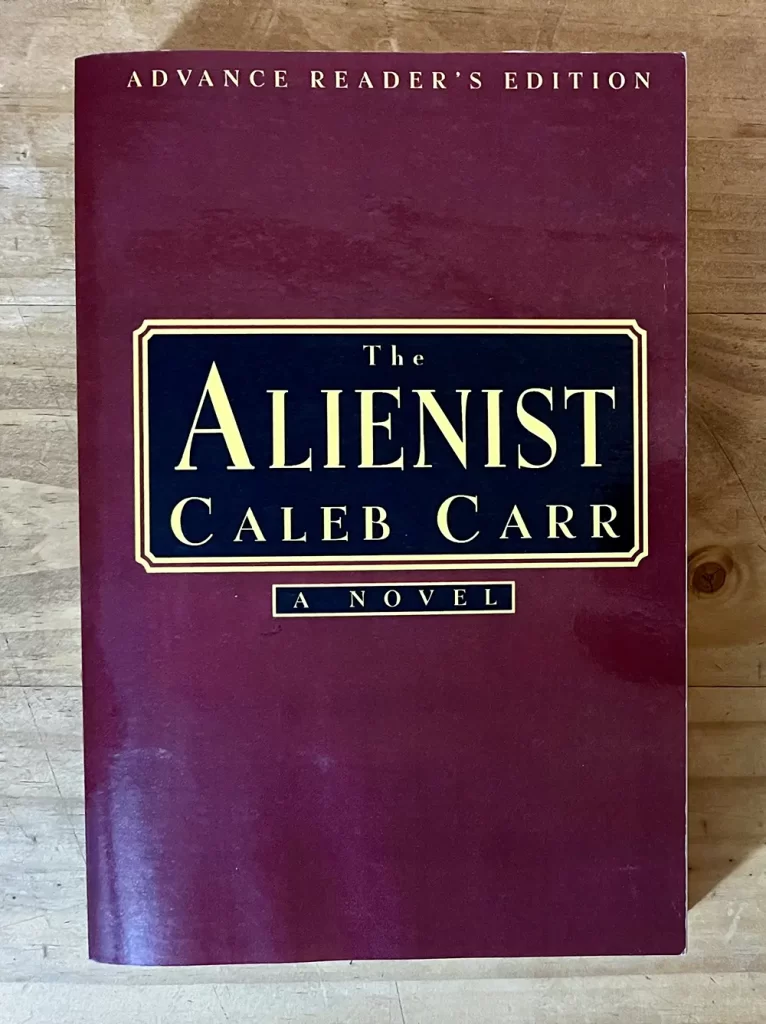

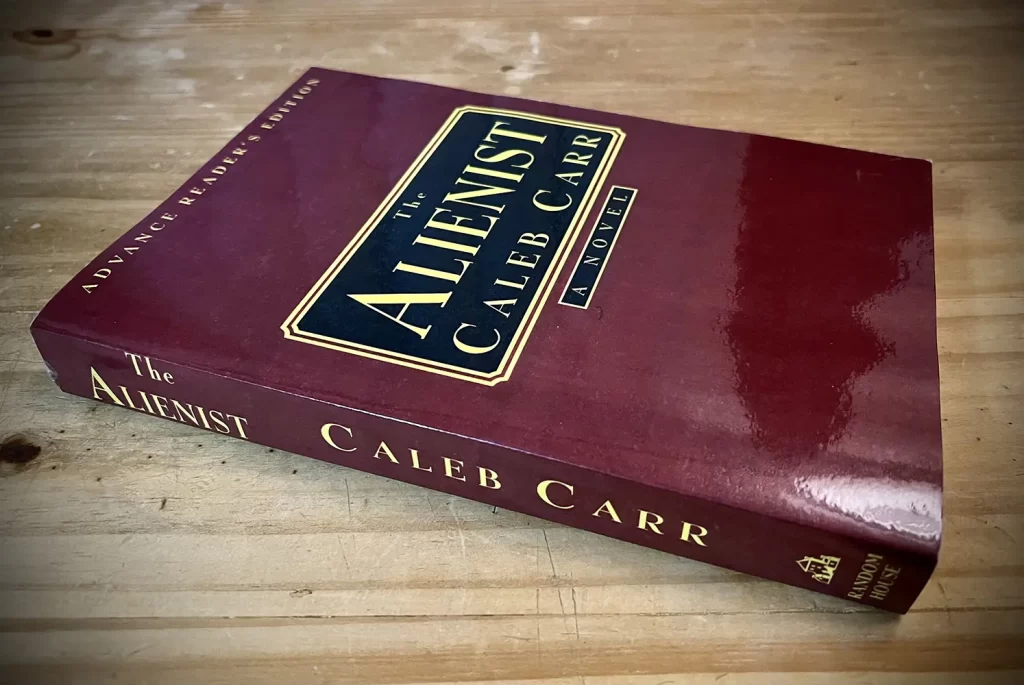

Finally, advance reader copy (or ARC) editions were also distributed for The Alienist to build buzz and anticipation for its impending release, an example of which can be seen below. Although the binding is still plain (this time maroon), the same typeface and title design that would come to be used on the first hardback edition has now appeared, and you can see the novel transitioning to its final finished form. On the back cover, the novel’s finalised blurb appears.

The publication would soon follow in March of 1994, but the whirlwind wasn’t over yet!

The next installment of this 30th anniversary series contains the story of the novel’s release and photographs of first and special editions of the novel. You can continue reading here. And, of course, if any visitors have further details about the editions shown here they would like to share, please feel free to leave a comment or get in touch.

Caleb passed away on May 24’Th, according to his publisher, from cancer. He was able to publish My Beloved Monster, a tribute to his cat Masha, who predeceased him. My wife Cynthia Schulte worked with him when he was a writer at Paramount Studios for Family Ties.

Lawrence J. Schulte

Thank you for posting, Lawrence. Yes, I was deeply saddened by Caleb’s loss last month. If you have a look at the blog, you will see our memorial post to him. I didn’t realize he been a writer for Family Ties! I appreciate you sharing, and I hope your wife has fond memories of that time.

I used to live in the lower east side. I followed every step in the alienist. I was very saddened to hear of Caleb Carr’s. A great mind gone too soon.

I am deep into the Alienist for the fourth time (my copy is falling apart from wear) and each time I am more amazed at the brilliance of Mr. Carr’s writing in capturing New York at the turn of the century. I grew up in New York (69th Street and Third Avenue) in the 1940’s and 50’s and his prose drew vivid pictures for me of places and structures that I recall seeing and/or visiting some 50 years later. What is disappointing is that I never got a chance to speak with my father and, more importantly his Irish cop brothers, about what is was like on the police force so corrupt as laid out by Mr. Carr.

Thanks for sharing, William. Yes, Caleb’s descriptions of New York are wonderfully evocative. I know how disillusioned he grew in recent years that the New York of today no longer embodies the city he knew so well — I’m so glad we at least have works like The Alienist to recapture some of the character it once had.