Last year I began the slow process of completing the supporting character profiles for the historical figures that appear in The Alienist. To do this, I have aimed to read at least one biography for each of these figures to aid me in completing their profile. While this proved to be a fascinating process for the first figure on my list, Police Superintendent Thomas Byrnes, it has resulted in my putting together a considerably longer profile than I had originally intended! As a result, I have only posted a summary of Byrnes’ role in the novel on the supporting characters list, and have decided to post his full character profile here instead as a history blog. So, if you are interested in learning more about this complex and interesting character, please read on. For any interested visitors, you can find the sources used in putting together this profile at the conclusion of the blog.

Early Life and Career

Although Thomas Byrnes, former Police Superintendent and Chief Inspector of the Detective Bureau, only appears in The Alienist on one occasion, he plays a prominent role in the novel behind the scenes and is mentioned a number of times throughout the text. Born in Ireland in 1842, Thomas arrived in New York City as a 10 year old when his family fled the Potato Famine, and grew up in the notorious Five Points district. When his father began drinking heavily and walked out on the family following the death of Thomas’ younger brother, Thomas and his mother were left to fend for themselves. To help them get by, Father Coogan of St. Patrick’s Cathedral managed to obtain a position for Thomas as helper in a firehouse, while his mother worked as a seamstress and his two sisters found employment as house maids. Even though Thomas had never been formally schooled, Father Coogan helped in this as well by providing his young charge with books for self-education.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, 19 year old Thomas joined Ellsworth’s Zouaves, the Eleventh New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment, and served during the Battle of Bull Run. He did not otherwise see much combat during his two years in the Union Army, and returned to New York following his discharge from the service in 1863. Shortly after this, he joined the New York City Police Department as a patrolman, and saw his first major action when the draft riots broke out. During the riots, in which a mob of Irish immigrants caused nearly $3 million of damage to the city and killed eighteen men during a week long spree following the first military draft, Thomas was recognised for his valiant efforts to protect the 233 children in the Orphan Asylum for Coloured Children, as well as assisting Police Superintendent John A. Kennedy who had been violently attacked and was lucky to escape with his life. Byrnes quickly rose through the ranks during the period that followed, becoming a Sergeant in 1869 and Captain of the Fifteenth Precinct in 1870 at only 28 years of age.

Byrnes’ posting in the Fifteenth Precinct undoubtedly helped his remarkable rise from Captain to Chief Inspector of the Detective Bureau during the ten years that followed. During his time as Captain, Byrnes investigated a myriad of cases ranging from petty theft to murder, and his name appeared in newspaper crime reports on an almost weekly basis. None of his cases, however, were was as well-publicised as the Manhattan Savings Institution heist of 1878. The robbery remains one of the greatest in New York’s history, with $3 million in bonds and cash (over $50 million in today’s dollars) stolen from the bank’s vault. During the long and complex investigation that followed, Byrnes successfully identified most of the culprits but there was a frustrating lack of convictions in the case due to the suspected bribery of jurors. Even so, the case helped to cement Byrnes’ reputation as an unrelenting crime fighter willing to go to any lengths to protect the interests of New York’s wealthiest citizens.

Inspector and Chief of Detectives

In 1880, Thomas Byrnes was promoted to Inspector and Chief of Detectives. Consistent with his reputation as a champion of the rich and powerful, one of his first acts was to open new detective offices in the New York Stock Exchange Building and 17 Wall Street, along with instituting a “dead line” at Fulton and Liberty Streets, whereby any known thieves found south of that line could be arrested on sight. At this time, detectives in New York City worked out of their assigned precinct houses as they did not yet have a central headquarters. It was not until New York State Legislature passed an act in 1882 to establish the Central Office of Detectives that the Detective Bureau was consolidated under one roof at 300 Mulberry Street. When this took place in 1883, all detectives in the city were placed under Byrnes’ direct command and the various methods he had developed over the prior ten years were standardised within the force.

Although the Isaacson brothers in the Alienist books lament Byrnes’ seemingly archaic methods of investigation, J. North Conway writes in The Big Policeman that only “hit-and-miss methods” of criminal investigation had been employed in the city’s police force prior to Byrnes. By comparison, his methods–which included keeping methodological records of photographs and detailed histories of all known criminals (the Rogues’ Gallery), random roundups of criminals to obtain information on past or future crimes, providing out-of-town professional criminals with immunity provided they committed no crimes in the city and registered with him in advance, and maintaining a vast network of petty criminals who informed on hardened criminals–were considered so successful that even President-elect Grover Cleveland placed Byrnes in charge of security during the 1885 inauguration ceremonies in Washington, D.C.

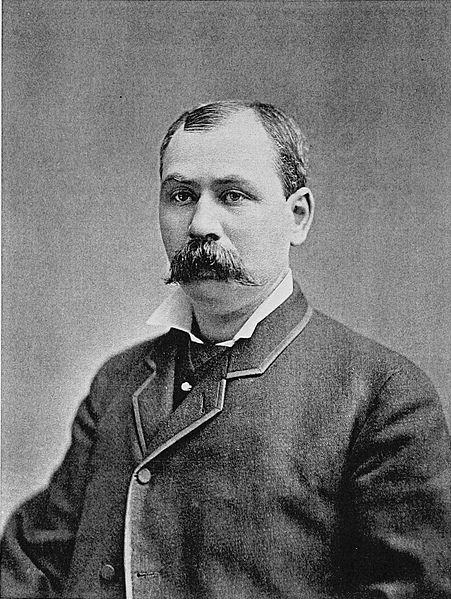

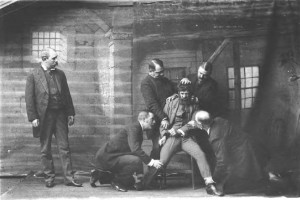

However, the imposing Chief Inspector, who stood over six feet tall, had a drooping handlebar moustache, and always had a cigar to hand, was most well-known for his controversial methods of interrogation, commonly referred to as “the third degree.” Even though he told a reporter that “the third degree should be a psychic rather than a physical process,” he ultimately had no scruples about using psychological or physical torture to obtain the information he wanted, whether that involved beating suspects in the stomach or genitals so there would be no physical bruises, or using paraphernalia such as thumb screws, sweat boxes, or solitary confinement. In his 1887 memoir, Police Commissioner Walling expressed concern that Byrnes’ methods, effective during cases such as the Manhattan Savings Institution heist, were not adequate in murder cases where evidence, not merely confession, was critical for conviction. This was certainly the case in Byrnes’ most notable failure when a Jack the Ripper copycat struck on the New York City waterfront in 1891, disembowelling prostitute Carrie Brown in the East River Hotel.

Having publicly stated that, “It would be impossible for crimes such as Jack the Ripper committed in London to occur in New York and the murderer not to be found,” Byrnes was under considerable pressure for a timely arrest; yet he, like Scotland Yard before him, hit nothing but dead ends. Finally, out of desperation to restore his reputation, he arrested Ameer Ben Ali, an immigrant Brown had been drinking with on the night she was murdered. Ben Ali, however, had no motive for the crime, and Jacob Riis, one of the first crime reporters on the scene, even filed an affidavit stating that he hadn’t seen any blood on the doorknob of the room in the hotel where Ben Ali spent the night. Even so, Ben Ali was convicted and served nearly eleven years in prison before he was finally released on the basis of evidence that had not been presented in the original trial: Brown’s room key and a bloody shirt had been found in a flophouse in New Jersey where it was impossible for Ben Ali to have deposited them.

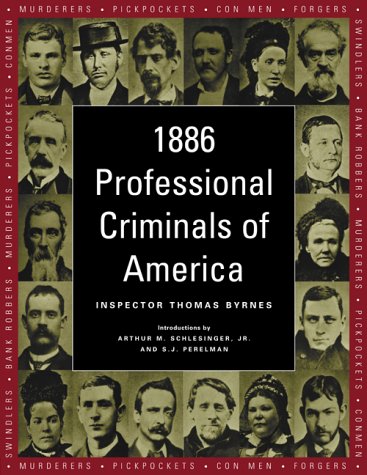

Nevertheless, Thomas Byrnes’ mastery of self-promotion helped him retain his reputation as New York’s premier detective through any rough patches. In 1886, he published Professional Criminals of America using information compiled as part of his Rogues’ Gallery, and reportedly sold 20,000 copies. He also preferred to work in secrecy, restricting other detectives’ access to the press, and holding back information about arrests until he had already obtained confessions. Even though he disdained “the detective of fiction,” stating that, “The detective of fact owes nothing to the detective of fiction … there is nothing like that in real detective work,” he even allowed himself to be featured as a central character in Julian Hawthorne’s series of mystery novels, including A Tragic Mystery (1887), The Great Bank Robbery (1887), An American Penman (1887), Section 558 (1888), and Another’s Crime (1888).

The End of a Celebrated Career

Byrnes was promoted to Police Superintendent in April of 1892 after his predecessor’s sudden departure following the Reverend Dr. Charles H. Parkhurst’s damning investigation into vice and police corruption in February and March of the same year. Even though Byrnes did put in place a limited number of conciliatory measures over the next two years to placate the reform groups, he ultimately defended his men against the charges laid at their door. Moreover, disgruntled that private organisations such as Parkhurst’s Society for the Prevention of Crime had started trying to execute arrest warrants, he went to some trouble to discredit the vocal Reverend, even arresting one of his investigators, Charlie Gardner, in a sophisticated sting involving exotic marked gifts and cash. Byrnes’ efforts were ultimately inadequate, however. The public had heard Parkhurst’s message, and they wanted reform.

During the Republican-led Lexow Committee investigation into crime and corruption in the city that followed, Byrnes was never personally tarred with the brush of corruption. However, New York’s most famous and popular detective still struggled to provide a reasonable explanation for how he had managed to amass a small fortune of $300-$350,000 (over $5 million in today’s dollars) on a Captain’s salary of $2,750 and Superintendent’s salary of $5,000, and his claims of careful investments following advice from his Wall Street friends such as Jay Gould were difficult to believe. Thus, when the Committee issued their scathing report into police corruption in early 1895, it was only a matter of time before Byrnes realised that he would have to admit defeat in order to spare his reputation. In May of the same year, he finally tendered his resignation, and the crusading Theodore Roosevelt, who had been placed on the board of police commissioners by the newly elected reform-minded Mayor William L. Strong, accepted it.

The Alienist, which is set in 1896, takes place approximately one year after the events that had led to Byrnes’ resignation. To read about his role in the novel, please see his profile on the supporting characters list. In real life, Thomas lived out his retirement years far from the taint of corruption at his Upper West Side home located at 318 West 77th Street with his wife, Ophelia, and five daughters, Adelaide, Isabelle, Jessie, Amy, and May. The family took his retirement as an opportunity make several crossings to Europe over the years that followed, and although he tried his hand at real estate investment, he ultimately found it impossible to stay away from the profession that had occupied so much of his life. He opened a successful private Wall Street detective agency, and even provided occasional law enforcement advice to New York’s mayors and police officials. On May 7, 1910, Thomas died of stomach cancer in his home at the age of 68.

Sources and Further Reading

Thanks for the post. Inspector Byrnes was the father of my Great Grandfather’s wife May O. Byrnes. I have been trying to find out more about the inspector’s parents (names, dates, place of origin in Ireland, etc.). If you have any information about his father James Byrnes and Mother Rose (Doyle?) I would appreciate it.

Thank you for the kind words. All the sources I used are listed at the bottom of the post, although J. North Conway’s The Big Policeman was my primary reference material. I’ve had another look at the early chapters of that book in which Thomas’ childhood and parents are discussed, but no dates (other than the year of their arrival in New York) are provided. However, the book has an extensive bibliography, so you might be able to find something helpful to your search there. Sorry I can’t be of more help!

Hope you see this.. my husband is retired NYPD, Det. Thomas Byrne’s, and I am trying to find out if he is related to the “original” Det. Byrnes…

Any help would be appreciated.

Thomas Byrnes was my Great Great Grandfather. His daughter, Jessie was my Great Grandmother. We called her Ganny. I knew her as a child. My daughter is named after her. My great Aunt Amy was also alive when I was a child. I believe those were the only 2 sisters still alive at that time. I have a set of Vases that were in the NY home of Jessie’s sisters in NYC where my mom would go visit as a child. I have an album of Newspaper clippings the family kept of Thomas. The lineage of my immediate family was Thomas, Jessie (married Harry Skillman Clark), Harry S Clark Jr (my grandfather), Harriet Clark Hulse ( my mother), then myself . Fascinating to find a distant relative.

Dear Kim:

As I read your fine page, I noticed you included something that, having read Conway’s error laden ‘The Big Policeman’, is incorrect.

Thomas Byrnes was not on the NYPD force during the Draft Riots of mid-1863. Byrnes joined the force on December 10th, 1863.

Howard

Sincere thanks for the correction, Howard. Do you have any recommendations for a more accurate biography of Thomas Byrnes? I’d be most appreciative of any suggestions.

Dear Kim,

Last March I was made aware of Thomas F. Byrnes existence while doing a Google Search. I was dismayed when I learned accusations that he was a corrupt policeman. I had an Uncle who was a sheriff department with the rank of Sergeant. So I have an infinity for law enforcement at the time where they are the most despised at this given moment. I watch a documentary clip on YouTube about Theodore Roosevelt cracking down on police corruption. Claiming Thomas F. Byrnes was absolutely corrupt, and he ran a crime syndicate of police officers taking bribes, by letting saloon owners stay open until 1 am. Brothers were free to flaunt their vice and making fortune. So I would like to know how deeply involved Byrnes was in this. Did he permit officers to take monetary enticements? Support the idea of prostitution to run freely while evangelical Christians tried to lead a movement to crush this sin? He saw dollar signs while ignoring the ill repute that dominated the City of New York. I read online that he admitted to receiving more than $300,000 in graft. Is this true? Byrnes was never directly implicated in any corrupt practices.

People then and now don’t believe that he received stock tips. “On a salary of $2,000 a year, he built a fortune of over $350,000, which he attributed to sound investment advice from his Wall Street patrons.”

So, I guess it was wrong for a policeman such Thomas Byrnes to play the stock market when it was supposed to live a meager salary. People considered to be an indication of honest man who does not live above his own means.

Byrnes is the sole reason why the NYPD was corrupt in the late 1800s? Overall, was he an amoral man who was not serious about respecting the law with dignity, but used it as a cover to benefit from it through the immoral environment that dominated the city and shielded the rich and powerful and the vices of the flesh? Did he condone prostitution?

Finally, if they were brought to trial on police corruption, there would be enough evidence to convict him? Do you admire or despise him?