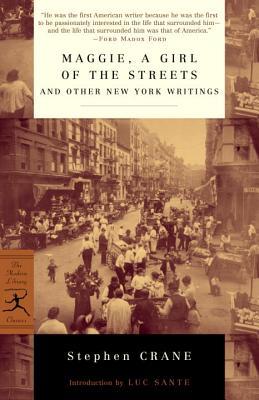

We return to the 17th Street book blogs this month by moving far away from the world of Fifth Avenue mansions and upper class society for a journey into the slums of old New York. Although Caleb Carr has not, to my knowledge, referenced the work of late nineteenth century journalist and novelist Stephen Crane as an influence for the Alienist books, readers of Crane’s atmospheric New York novellas will instantly recognise the same city that was so vividly portrayed in The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness. Given that I have utilised the 2001 Modern Library Classics edition of Crane’s New York writings for this blog, which contains the definitive versions of his novellas Maggie, A Girl of the Streets (1893) and George’s Mother (1896), along with a comprehensive selection of his other Bowery tales, we will be considering both of Crane’s New York novellas together in the following post, rather than just focusing on Maggie, the most famous of the pair.

What’s it about?

Maggie, A Girl of the Streets opens with a scene that would not be out of place if glimpsed in one of the Alienist books. Jimmie, “the little champion of Rum Alley,” is embroiled in a fight with a gang of street urchins from nearby Devil’s Row. Battered and bruised, with blood “bubbling over his chin and down upon his ragged shirt,” the fight only comes to a halt when Jimmie’s father arrives on the scene, obtaining his son’s obedience through violence of his own. As this opening scene suggests, life in the family home is no less frightening than life on the streets for Jimmie, his quiet older sister, Maggie, and his confused and neglected baby brother, Tommie. With a drunken father and an equally drunken, vicious mother who can match her husband blow for blow, Maggie, A Girl of the Streets chronicles the stories of Jimmie and Maggie as they grow up to find their own places in the poverty-stricken world that surrounds them, with one child embracing their fate while the other tries in vain to search for a way out.

In George’s Mother, the sequel to Maggie, A Girl of the Streets, we return once more to the tenement building of Jimmie’s family. Unlike Maggie, however, George’s Mother explores the inner struggles of George Kelcey, the hard-working son of a loving, patient, and temperance supporting mother who has only one fear for her sole surviving child: that he will succumb to the vice that lurks on every street corner in their neighbourhood, and turn to drink. Through these contrasting family portraits, Crane vividly demonstrates the powerful hold that alcohol maintained in the lives of the poor in late nineteenth century New York, and doesn’t shy away from chronicling its effects on the lives of children and adults alike, both inside and outside the family home.

My thoughts

My first impression upon reading the opening lines of Maggie, A Girl of the Streets, along with George’s Mother following it, was that I had once more been transported back into the world that John Moore and Stevie Taggert so vividly describe in The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness. Once again, the reader is there, looking down on the dusty streets from surrounding tenement buildings as we hear the howls arising from a gang of children hurling stones at a small boy who is standing atop a heap of gravel in a vain attempt to defend the honour of Rum Alley. Similarly, in George’s Mother we find ourselves “in the swirling rain that came at dusk” on a broad avenue glistening “with that deep bluish tint which is so widely condemned when it is put into pictures,” through which we witness,

George’s Mother, Chapter I

… the endless processions of people, mighty hosts, with umbrellas waving, banner-like, over them. Horse-cars, aglitter with new paint, rumbled in steady array between the pillars that supported the elevated railroad. The whole street resounded with the tinkle of bells, the roar of iron-shod wheels on the cobbles, the ceaseless trample of the hundreds of feet. Above all, too, could be heard the loud screams of the tiny newsboys, who scurried in all directions. Upon the corners, standing in from the dripping eaves, were many loungers, descended from the world that used to prostrate itself before pageantry.

Although Crane’s masterful portraits of the streets he knew so well are reason enough for any Alienist reader to pick up these stories, it is his examination of the role that alcohol played in the lives of the poor, and its contribution to other forms of vice ranging from violence to prostitution, that make these stories so compelling.

In Maggie, for instance, we see that despite the terror two alcoholic, violent parents could induce in the children of the family—in one scene, even Jimmie, a hell-raiser in his own right, huddles in a corner of their tiny family flat until dawn out of fear of waking his sleeping parents following a particularly vicious fight—the children find themselves either directly or indirectly drawn to a similar life in adulthood due to the high social position individuals such as bartenders held in the neighbourhood. Moreover, although we see a very different sort of parent in George’s Mother, the social power of the saloon comes into play in George Kelcey’s story as well.

George’s Mother, Chapter XII

Kelcey sometimes wondered whether he liked beer. He had been obliged to cultivate a talent for imbibing it. He was born with an abhorrence which he had steadily battled until it had come to pass that he could drink from ten to twenty glasses of beer without the act of swallowing causing him to shiver. He understood that drink was an essential to joy, to the coveted position of a man of the world and of the streets. The saloons contained the mystery of a street for him. When he knew its saloons he comprehended the street. Drink and its surroundings were the eyes of a superb green dragon to him. He followed a fascinating glitter, and the glitter required no explanation.

Thus, just as it does in the Alienist books, environment plays a prominent role in the shaping of character in Crane’s work. In addition, the limited choices available to women in the late nineteenth century, along with societal double standards, is another prominent theme in both novellas that is also shared with the Alienist books. For example, Maggie’s admiration of Pete, a local bartender of some social standing in the novella Maggie, strongly reminded me of Kat Devlin in The Angel of Darkness declaring that she needed “a man, Stevie, a man of my own” in order to “be somebody.” Unfortunately, we see a similar path to Kat’s unfold for Maggie when her character is called into question as a result of her attempts to get a man of her own, a problem the men in the story never have to contend with. In George’s Mother, on the other hand, we see Mrs. Kelcey, a homemaker, hold little power to influence the choices her son makes due to her dependence on his income.

Although I highly recommend Crane’s novellas to any Alienist reader interested in learning more about life in the slums during the 1890s—and I think they would go particularly well if they were read alongside Jacob Riis’ How The Other Half Lives which, if written in a less empathetic manner than Crane’s work, is just as important—I should warn readers that there are one or two elements that may cause some problems. First, while Crane’s uncompromising naturalism is part of the attraction of his work, it extends to his dialogue as well, with his incorporation of the local accents and dialects recorded faithfully. In Maggie, for example, our socially prosperous bartender Pete tells Maggie a story that he’s sure will impress:

Maggie, A Girl of the Streets, Chapter VI

“I met a chump deh odder day way up in deh city,” he said. “I was goin’ the see a frien’ of mine. When I was a-crossin’ deh street deh chump runned plump inteh me, an’ den he turns aroun’ an’ says, ‘Yer insolen’ ruffin,’ he says, like dat. ‘Oh, gee,’ I says, ‘oh, gee, go teh hell and git off deh eart’,’ I says, like dat. See? ‘Go teh hell and git off deh eart’,’ like dat. Den deh blokie he got wild. He says I was a contempt’ble scoun’el, er something like dat, an’ he says I was doom’ teh everlastin’ pe’dition an’ all like dat. ‘Gee,’ I says, ‘gee! Deh hell I am,’ I says. ‘Deh hell I am,’ like dat. An’ den I slugged ‘im. See?”

While it’s not hard to see how such an eloquent speech could win a girl over, and you do tend to adapt reasonably quickly after reading a several such passages, some of the longer blocks of dialogue can still be quite difficult to interpret (especially when alcohol is involved), and it can also become repetitive, just as several of the lines in Pete’s preceding story were repeated. A second element of Crane’s storytelling that has come under some criticism from reviewers is the lack of depth one or two of his characters appear to have. Even though this is normally an important consideration for me as I generally prefer character-driven novels, I didn’t notice this as a particular problem in Maggie or George’s Mother, so you may not have an issue either.

So, if you would like to return to the world of the streets you were introduced to in The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness, or if you would simply like to gain some greater insight into slum life in the 1890s as written by a novelist who lived in both the time and place, I do recommend picking up a copy of Maggie, George’s Mother, or better yet both together in a collection such as the Modern Library Classics edition. Just prepare yourself for a little—or a lot—of alcohol and Bowery slang.