Here we are again at the close of another year. New Year’s Eve in 2014, however, is a particularly noteworthy date for 17th Street. Not only does it mark the conclusion of the 20th anniversary year of The Alienist‘s publication, it also marks the 9th anniversary of the website. In consequence, I’m pleased to be presenting the final part of the special three part blog series overviewing The Alienist‘s central themes in honor of both milestones.

In the preceding two parts of the blog series, we have explored several of the novel’s central themes, ranging from corruption and hypocrisy to domestic violence and childhood trauma. As we conclude the series in Part Three, we will continue the discussion begun in Part Two that the role of the mother was one of the key differences between the early childhoods of Dr. Kreizler and John Beecham, leading us to explore themes in the novel relating to the role of women in society, the role that mothers can play in domestic violence and childhood trauma, trust and betrayal, regaining control, psychological determinism, and changing the way we think about mental health.

N.b. The following post contains major spoilers for The Alienist. To read a spoiler-free synopsis, please refer to the summary page.

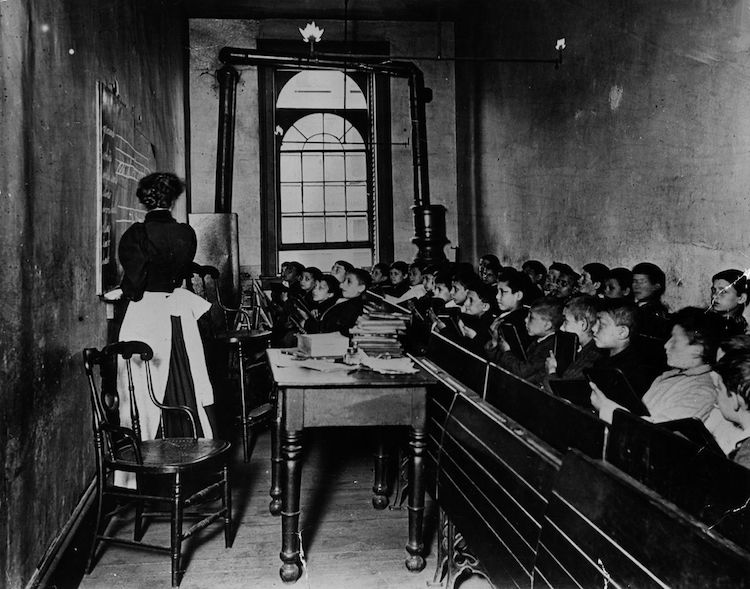

The Role of Women in Society

Although it may seem as though The Alienist‘s sequel, The Angel of Darkness, is the stronger of the two novels in terms of themes tied to the feminine—that is, in its examination of what drives women to kill—it would be a mistake not to acknowledge that the role of women in society, and the role that mothers can play in domestic violence and childhood trauma more specifically, are themes that are as prominently placed in the original novel as in its successor. As early as Chapter 5 in The Alienist when we are introduced to Sara Howard, a close childhood friend of John Moore and one of the first female police secretaries, the unique experiences—and frustrations—of women in New York society of 1896 are brought to our attention.

“Sara—with all the professions open to women these days, why do you insist on this one? Smart as you are, you could be a scientist, a doctor, even—”

“So could you, John,” she answered sharply. “Except that you don’t happen to want to. And, by way of coincidence, neither do I.”

The Alienist, Chapter 5

Sara’s inclusion in the novel as an intelligent, fiery, competent, and determinedly single-minded woman with the goal of becoming New York’s first female police officer is no accident. While her employment in the novel as police secretary is a clear nod to Theodore Roosevelt’s controversial decision to hire a female secretary upon becoming Police Commissioner (his real secretary, Minnie G. Kelly, was “young, small and comely, with raven black hair”; see 17th Street’s Island of Vice book blog for more information), she is also representative on a more general level of those women in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who had begun to push back against the prevailing view that the only proper role for women in society was as a doting wife and mother in the home; an ideology that had dominated American culture from the late eighteenth century onwards (see 17th Street’s Education of Sara Howard history blog series for more information). However, it is important to note that Sara’s purpose in the novel in terms of social commentary is not strictly historical, as Caleb Carr pointed out in an interview with Salon in 1997:

I wanted to write a book with a female character whose reasons for being in the story did not depend on her falling in love with somebody. Women are still being brought up to believe that they have to build their bodies and their minds toward relationships and not toward independent existences of their own choosing. And I wanted to show that women can do that.

I, for one, appreciate Mr. Carr’s stance on this topic. Only last month The New York Times ran a piece pointing out that despite the bleak statistics on marriage, a large number of young women still see the “fairy-tale wedding” as their crowning moment in life, with the wedding gown continuing to be viewed by many as “the most important dress in the life of a woman,” as Oscar de la Renta stated in a recent Vogue magazine spread. As the author of the NYT piece pointed out, “He probably wasn’t considering what a woman would wear, say, as she accepted a Nobel Peace Prize, or was being sworn in as the president of the United States.” Clinical psychologist Sue Johnson went on to explain this mentality in the NYT piece using language strongly reminiscent of the woman’s sphere ideology of the nineteenth century, “Hillary Clinton might be the first female president, but a woman still wants this badge of legitimacy that she is wanted and desired by a man.” Accordingly, the inclusion of an independent female who remains single by choice in a bestseller such as The Alienist is a breath of fresh air, even if, as Dr. Kreizler observes to John:

“Women of such temperament,” he said as we moved to the carriage, “do not seem fated for happiness in our society. But her capabilities are obvious.”

The Alienist, Chapter 9

“There is more than one type of violence, Doctor.”

Taking the role of women in society one step further, one of the less well-recognized themes in The Alienist is the role that women, specifically mothers, are capable of playing in domestic violence and childhood trauma. Although most readers would recognize this theme from The Angel of Darkness where the murderer was a woman who, lacking Sara’s financial freedom and family support, had been expected to fulfill the role of wife and mother—a role to which she was wholly unsuited, and was unable to come to terms with—the theme is, in fact, just as important in The Alienist.

As has already been discussed in Part Two, one of the key differences in the contextual backgrounds of The Alienist‘s protagonist, Dr. Kreizler, and antagonist, John Beecham (originally Japheth Dury), is the role their mothers played in their respective childhood homes. Where Dr. Kreizler’s mother is described as “passive,” failing to step in when the elder Kreizler was physically and psychologically abusing his son, Beecham’s mother played an “active” role in her son’s abuse and was ultimately the original perpetrator of the abuse. Interestingly, the origins of the maternal violence we witness in The Angel of Darkness is a reflection of the roots underlying the viciousness Beecham’s mother displays toward her son in The Alienist, with the character who first identifies these origins being the sole female representative on the investigative team, Sara.

Sara’s preferred theory was that the woman had not wished to bear children in the first place. She’d only done so, Sara speculated, because she’d either become pregnant or had been offered no other socially acceptable role to play by the particular world in which she lived. The end result of all this was that the woman had deeply resented the children she did bear, and for this reason Sara thought there was an excellent chance that the killer was either an only child or had very few siblings: childbearing was not an experience that the mother would have wanted to repeat many times.

The Alienist, Chapter 24

When John and Dr. Kreizler visit Beecham’s brother, Adam Dury, Sara’s theory is proven correct through the discovery that Beecham’s conception was the product of rape on the part of his father.

“In what way was he not [odd]? … I suppose you couldn’t expect much more, from a child born out of anger and unwanted by both his parents. To my mother he was a symbol of my father’s savagery and lust, and to my father—to my father, much as he wanted more children, Japheth was always a symbol of his degradation, of that terrible night when desire made an animal out of him.”

The Alienist, Chapter 34

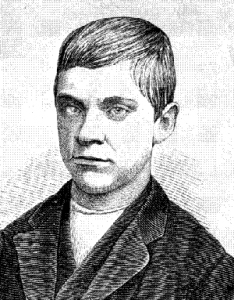

It is important to note, however, that it doesn’t appear as though Beecham’s mother employed the same kind of physical violence toward her son that his father did. As Sara points out to Dr. Kreizler during the team’s analysis of the letter Beecham sends Mrs. Santorelli, we see in Beecham’s writing the signs of a child who has been “harassed, embarrassed, blamed … a boy who’s been scrutinized and humiliated regularly, whose been made to feel that he himself is filth, without ever experiencing a place or person of refuge.” Although Dr. Kreizler is the primary character who finds it most difficult to come to terms with Beecham’s mother having played this kind of “active” role in his early trauma due to the nature of his own abusive childhood (see Part Two), he eventually comes around to Sara’s viewpoint once he is reminded of Jesse Pomeroy’s case. Pomeroy, too, had been scrutinized and humiliated by his mother, causing him to act out violently in search of human contact, behavior Dr. Kreizler tries to explain to a bewildered John.

“But isn’t there something—well, something inside him, inside of any person that would object to that kind of situation? I mean, wouldn’t there be sadness or despair, even about his own mother? The desire to be loved, at least? Isn’t every child born with—”

“Be careful, Moore,” Kreizler warned as he lit a cigarette of his own. “You’re about to suggest that we’re born with specific a priori concepts of need and desire—an understandable thought, perhaps, were there any evidence to support it. The organism knows one drive from the beginning—survival. And yes, for most of us, that drive is somehow intimately bound up with the notion of a mother. But were our experiences terribly different—if the concept of mother suggested frustration and finally danger, rather than sustenance and nurturing—the instinct for survival would cause us to structure our outlook differently.”

The Alienist, Chapter 24

Nevertheless, despite Dr. Kreizler’s insightful preceding analysis about the need to be careful not to make assumptions that we are born with a priori concepts of the mother in terms of survival, at no point in The Alienist does he follow his argument to its logical conclusion as it applies to “passive” mothers such as his own. Specifically, that a mother’s failure to step in to protect her child from abuse is bound to impact on that child’s view of the mother—and women, generally—as being representative of survival or safety. Not only that, it is likely that the concept of survival would become even more confusing for the child if at any stage the child took on the role of protector in the household for the mother.

Perhaps not surprisingly, we see just this type of complex relationship reflected in Dr. Kreizler’s adult relationships. That is, he takes on the function of protector in many of his most emotionally meaningful relationships, especially those involving vulnerable populations such as children (e.g., Stevie Taggert and the children at his Institute). He also goes out of his way to protect Mary Palmer, his love interest, throughout the course of the investigation, and when she is killed in a home invasion in Part III of the novel while he is away on a trip, he refuses to listen when John tries to tell him that he isn’t responsible for her death, going so far as to state, “We’ve been hunting a killer, John, but the killer isn’t the real danger—I am!” Notably, Mary died protecting Stevie in just such a way that Dr. Kreizler’s mother failed to do for him.

Unlike Dr. Kreizler whose relationship with his mother in all likelihood prompted him to pursue relationships in which he could take on the role of protector, Beecham’s bitter relationship with his mother eventually led him to “shun the company of women generally.” Indeed, John and Sara reason that, “if one of Japheth’s parents had been the ‘primary’ or ‘intended’ victim of his murderous rage, it was almost certainly his mother.” Consequently, the most likely reason he was targeting cross-dressing boy prostitutes instead of women was because:

The hateful relationship between Japheth Dury and his mother must, we reasoned, have spilled over into self-hatred, as well—for how could any boy despised by his mother fail to question his own worth? Thus Japheth’s anger had crossed sexual lines, becoming a sort of hybrid, or mongrel; and it had found its only release in destroying boys who embodied, in their behavior, similar ambiguity.

The Alienist, Chapter 37

As should hopefully be clear by now, the effect of domestic violence and childhood trauma is capable of extending far beyond physical abuse. Making reference to just this point, Sara astutely observes midway through the novel that, “There is more than one type of violence, Doctor.”

Revisiting Hypocrisy

As we saw in Part One, one of the most prominent themes within The Alienist is that of hypocrisy. Before moving on, it is therefore worth briefly revisiting the theme given that we can now see just how far into the novel it permeates, even underlying some of the killer’s behavior. Specifically, despite the violence employed by John Beecham’s parents within the walls of their family home, we discover during John and Dr. Kreizler’s visit to Beecham’s brother that his father, Victor Dury, was a Reformed Church minister with missionary ambitions. His mother was also extremely religious; indeed, despite the poor marital relations she maintained with her husband, she is described as having enjoying that part of his life, at least until he lost his post. Beecham, then, grew to loathe the type of hypocrisy his family embodied: abusive behind closed doors while fervently preaching the word of God.

Even so, Beecham goes on to embody such hypocrisy himself. For example, while he didn’t like the violence that had been inflicted upon him, he also “picked it up as a method of getting by.” Thus, although the murders he commits create a deep self-loathing, he is equally incapable of stopping himself from committing them, as Dr. Kreizler explains.

“…He has become what Professor [William] James calls a ‘mere walking bundle of habits,’ and to abandon those habits would, he fears, mean abandoning himself. You remember what we once said about Giorgio Santorelli—that he came to associate his psychic survival with the activities that caused his father to beat him? Our man is not so very different. He no doubt enjoys his murders as much or as little as Giorgio enjoyed his work. But for both of them those activities were, and are, vital, despite the deep self-loathing they may create…”

The Alienist, Chapter 21

Trust & Betrayal

Although John Beecham’s primary trauma originated in childhood with his mother and father—a significant betrayal in itself—the final straw for his psychological wellbeing was the severe betrayal he experienced outside the family home. His brother, Adam, reveals to John and Dr. Kreizler on their visit to his farm that his younger brother had been raped at the age of eleven by a farmhand known as George Beecham whom Adam had befriended and Japheth had come to trust. Not only does this incident explain Japheth’s later name change, it also explains why he selected the victims that he did.

Since the beginning of our investigation, it had been clear to all of us that we were dealing with a sadistic personality, one whose every action betrayed an obsessive desire to change his role in life from that of the victim to that of the tormentor. It was perversely logical that, as a way of initiating and symbolizing this transformation, he should alter his name to that of a man who had once betrayed and violated him; and it was just as logical that he should keep that name when he began to murder children who apparently trusted him in just the way that he had once trusted George Beecham. There was a clear sense that, careful as the killer doubtless was to cultivate that trust, he despised his victims for being foolish enough to give it. Again, he hoped to eradicate an intolerable element of his own personality by eradicating mirror reflections of the child he’d once been.

The Alienist, Chapter 37

However, as with most themes in the novel, the consequences of betrayal are not restricted to John Beecham’s character. The murder victims clearly had their trust betrayed as well, and as we saw in Part Two, Sara also appears to have suffered some kind of significant betrayal of trust, the details of which have not yet been explored in either Alienist novel. Dr. Kreizler, too, is another character who appears to have problems trusting given that he maintains a “peculiar quality of emotional distance,” even toward those characters he is closest to, including his oldest childhood friend, John, and his ward, Stevie.

Regaining Control

Closely related to the theme of trust and betrayal is the concept of needing to maintain control—or, more accurately, to regain control—a common trait in individuals who have, in childhood, been trapped in an abusive environment in which they had little or no control and from which they were unable to escape. Regaining control in adulthood, and then fearing what will happen if they relinquish any degree of that control—for example, by trusting another person—is therefore understandable, even if the consequences of such reluctance can ultimately be counterproductive or even dysfunctional.

Although we see hints of this trait in Dr. Kreizler during the investigation (e.g., when he decides that only he and John should face Beecham in the final confrontation without consulting the team), in no character is it as profound as in Beecham himself, ranging from his deviousness to his tendency to use rooftops as the settings for his murders, as Lucius Isaacson points out to the team at the conclusion of the investigation.

“What I’m saying is that the way to find out what he’s doing with his life now is to follow the trail of what makes him feel secure, instead of the trail of his nightmares. He’s hunting and killing on the rooftops, and his victims are children—all of which suggests that having control over situations is the most vital thing in his life.”

The Alienist, Chapter 38

Strengths, Not Weaknesses

Given the darkness inherent to many of the themes discussed thus far, you may find yourself wondering why someone such as myself has run a website dedicated to the book and its successor for such a long time. While part of the reason is that I, like Dr. Kreizler in the novel, think it is important to stare “ugly realities full in the face,” another part of the reason is that most of the central characters in the novel are not dark despite the darkness of their pasts. Indeed, if the novel and its sequel teach us anything, it is to recognize and appreciate our strengths, even if they are strengths born of adversity, rather than focusing on our weaknesses.

As Stevie describes in The Angel of Darkness, you would be “hard-pressed to name a fairer, more decent, or generally kinder man” than The Alienist‘s narrator, John, despite the sadness in his past. We see these traits throughout the novel, such as in his spontaneous decision to take Mary out for the day when she is feeling down, or when he takes a young boy under his wing to help him escape his current employment at a disorderly house. His loyalty is also irreproachable, with old friend Dr. Kreizler stating that he is “not a man to break [his] word.” Similarly, Stevie, whom nobody prior to Dr. Kreizler had “been able to get more than a bite or a punch out of,” shows himself to be both loyal and brave during the novel, being prepared to be beaten almost to his death rather than betray his guardian during the home invasion in Part III of the novel.

“They forced their way into the house, and shut Mary in the kitchen. Cyrus was in bed, which left Stevie. They asked him where you and Dr. Kreizler were, but—well, you know Stevie. He wouldn’t say.”

I nodded, and mumbled, “‘Go chase yourselves,'” softly.

The Alienist, Chapter 36

Dr. Kreizler’s housekeeper, Mary, whose traumatic past is nothing short of a nightmare, shows her bravery during the home invasion, too, when she dies trying to protect Stevie. The idiosyncratic Marcus and Lucius Isaacson, along with John, add much appreciated humor to the team as well as displaying a remarkable open-mindedness in pursuing unorthodox ideas in order to find answers to the questions that arise during the investigation, traits that presumably developed as a result of the struggles they faced as first-generation children of Jewish immigrants. Sara’s high principles and fiery determination, on the other hand, are the primary reason the investigation is able to continue at all following Dr. Kreizler’s withdrawal from the team toward the end of the novel.

Nobody in The Alienist, however, is more representative of strength arising from adversity than Dr. Kreizler himself. This is apparent as early as our first glimpse of the doctor when he is described as resembling “a hungry, restless hawk determined to wring satisfaction from the worrisome world around him.” While his early battles with his father may have caused him to “doubt his own judgment and abilities,” they also produced a man who never wavers in his resolve to fight similar injustices and to protect vulnerable populations such as abused children, a trait we have already touched upon that is perhaps best captured in a scene described by his ward, Stevie, in The Alienist‘s sequel.

At that point all eyes, including mine, turned to the back of the courtroom to get a glimpse of what was, for most of them, a familiar sight: the renowned alienist Dr. Laszlo Kreizler, one of the most hated yet respected men in the city, charging in, his long hair and cloak floating behind him and his eyes burning with coal-black fire. I had no way of knowing that I’d become accustomed to that sight, too; all I knew then was that he was the damndest person, with the damndest nerve, that I ever saw.

… At that he pointed in my direction and, for the first time, actually looked at me – and I’m not sure I’m up to describing all that was in the look:

His eyes sparkled with a message of hope, and the smallest, quickest smile told me to have courage. All in a rush and for the first time in my life, I felt like someone over the age of fifteen truly gave a goddamn about my existence.

The Angel of Darkness, Chapter 6

Although Dr. Kreizler’s fire and “mental belligerency” are the most prominent traits we witness in his dealings with adults, we also see softer traits emerge over the course of both Alienist novels as well, most commonly in his dealings with children: specifically, his patience, kindness, wisdom, and humor. However, perhaps it is Dr. Kreizler’s “ability to keep working through [his self-doubts] toward a better sort of life for our mostly miserable species,” as Stevie puts it at the conclusion of The Angel of Darkness, that is his most admirable quality of all.

Psychological Determinism & Changing The Way We Think About Mental Health

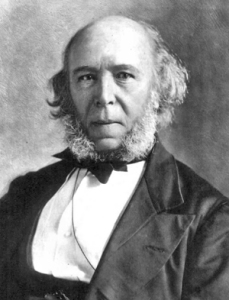

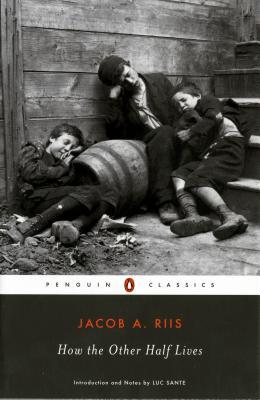

Beyond the characters, perhaps the most positive aspect of the novel is that as a result of its overarching theme of psychological determinism (once again embodied in the character of Dr. Kreizler through his theory of “context”), it actively helps to combat any stigmatic or dismissive views we might hold that are associated with mental health. As we have already discussed through the course of this blog series, all of the behaviors and personality traits we see in The Alienist‘s characters—both the good and the bad—arose out of their past experiences, even the killer’s. This concept, known as psychological determinism, is perhaps the most important in the entire novel, for almost every other theme that we have reviewed builds upon it. Importantly, determinism as presented in the novel found its roots, not only in philosophy, but also in the theories of evolutionists such as Charles Darwin and Herbert Spencer. As John explains:

While Spencer’s attempt to explain the origins and evolution of mental activity might have been wide of the mark, there was no arguing his belief that what most men consider their rationally selected actions are in fact idiosyncratic responses (again, established during the decisive experiences of childhood) that have grown strong enough, through repeated use, to overpower other urges and reactions—that have won, in other words, the mental battle for survival. Obviously, the person we sought had developed a profoundly violent set of such instincts; it was up to us to theorize what terrible series of experiences had confirmed such methods, in his mind, as the most reliable reaction to the challenges of life.

The Alienist, Chapter 13

Thanks to this approach we are capable of seeing that the symptoms of many psychological disorders are really coping mechanisms or adaptations that people have developed in order to cope with traumatic experiences, whether that trauma be overt (e.g., physical abuse) or covert (e.g., psychological abuse). Moreover, these coping mechanisms or adaptations are not only functional while the trauma is taking place—they are also necessary for survival, whether that survival be physical or psychological in nature. As John Briere, author of Principles of Trauma Therapy, states:

If we could somehow end child abuse and neglect, the eight hundred pages of DSM [the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders] (and the need for the easier explanations such as DSM-IV Made Easy: The Clinician’s Guide to Diagnosis) would be shrunk to a pamphlet in two generations.

Thus, if we take one thing away from The Alienist and its sequel, my hope is that they help to reaffirm that any stigmatic or dismissive attitudes associated with mental health that we might hold—whether they involve labeling someone (even ourselves) as “nuts” or “crazy,” attempting to argue that a depressed or anxious person can simply “choose” to be happy or carefree, or perceiving someone (again, including ourselves) only in terms of a diagnosis—are not only entirely unhelpful, they are also counterproductive. It is only once we start to view the symptoms of psychological disorders for what they really are that we can gain a more accurate understanding of why they developed and persist, as well as recognizing the importance of getting the necessary support to heal from whatever trauma was experienced in the first place so that the coping mechanisms or adaptations do not become maladaptive or dysfunctional in the future.

Conclusions

And with that, we reach the conclusion of this special three part book blog series. I hope you’ve found this blog series helpful for digging a little deeper into some of The Alienist‘s underlying themes, as well as gaining a better understanding of why I have taken the time to create 17th Street in the first place. There may, of course, be aspects of the novel that I haven’t covered here; however, as I stated in Part One, the preceding series is purely a personal interpretation of the novel and its themes. Happy reading!

Loved your blog!!! Loves The Alienator Show. Hopes for season 2.