As we fast approach the conclusion of the 20th anniversary year of The Alienist‘s publication, I am honoring the milestone for the second last time on 17th Street with Part Two of a special three part blog series examining the novel’s central themes. In addition to presenting The Alienist as a superb piece of historical fiction, Part One in the blog series explored two of the novel’s central themes—corruption and hypocrisy—to help to explain why the investigative team attracted so many “powerful enemies” as they pursued their killer. Specifically, it was their enemies’ fear of exposure of “all the hidden crimes that we commit when we close ranks to live among each other,” as Dr. Kreizler put it at the conclusion of The Alienist, that was so very dangerous to the city’s power brokers at the time. As we continue our discussion in Part Two, we will be examining these “hidden crimes” more directly as we explore some of the themes in the novel that relate to the hidden world of the family behind closed doors.

N.b. The following post contains major spoilers for The Alienist. To read a spoiler-free synopsis, please refer to the summary page.

Society’s Secret Sins

One of the more surprising twists in the final chapters of The Alienist was the assistance provided by Paul Kelly’s right-hand man, eat-’em-up Jack McManus, during John Moore and Dr. Kreizler’s final confrontation with the killer. Puzzled about why Kelly, a notorious gangster, might have decided to help the doctor in such an essential way given his efforts to cause mayhem and disruption earlier in the investigation (see Part One), one of the final scenes in the novel involves John visiting Kelly at the latter’s New Brighton Dance Hall. Although Kelly feigns ignorance about the part his henchman played in the crucial battle, he does provide John with one tantalizing hint regarding his motives.

“I’m not saying I know anything about it, of course. But ask yourself this when you get a free minute—of all the people who were up there tonight, who do you think is really the most dangerous to the boys uptown?”

The Alienist, Chapter 46

This view is reflected in the outrage we see the censor of the United States Post Office, Anthony Comstock, express during a meeting he and other prominent New York figures, including the famed financier J. P. Morgan, have with John and Dr. Kreizler early in Part III of the novel. Comstock claims during this meeting that he believes it is Dr. Kreizler’s intent to “spread unrest by discrediting the values of the American family and society” through the pursuit of an investigation that relies heavily on a theory founded in psychological determinism being found to have merit; specifically, Dr. Kreizler’s theory of “context” in which it is proposed that an individual’s personality and behavior in adulthood is determined by his or her experiences during infancy and childhood. Comstock is not alone in his concerns, with J. P. Morgan joining Comstock in expressing his misgivings about the implications of Dr. Kreizler’s theory as well.

“Mr. Comstock has the energy and brusqueness of the righteous, Dr. Kreizler. Yet I fear that your work does unsettle the spiritual repose of many of our city’s citizens, and undermines the strength of our societal fabric. After all, the sanctity and integrity of the family, along with each individual’s responsibility before God and the law for his own behaviour, are twin pillars of our civilization.”

The Alienist, Chapter 30

Although Dr. Kreizler successfully contends during the meeting that he has never “argued against the idea that every man is responsible before the law for his actions, save in cases involving the truly mentally diseased,” this is not the first time Dr. Kreizler has faced open opposition to his work or theories. Indeed, early in the novel we see John express his disbelief that Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt would so much as countenance the Doctor taking part in any police investigation given the general public’s opinion of his friend’s work.

“Take part in the investigation?” I said, dumbfounded. “Roosevelt, have you lost your Dutch mind? An alienist? A psychologist? … If word gets out that you’ve brought someone like Kreizler in—why, you’d be better off hiring an African witch doctor!”

Laszlo chuckled. “Which is approximately what most of our respectable citizens consider me.”

… Roosevelt braced himself against his desk and rocked quietly on his chair, watching Kreizler. “It would mean my job,” he said, without what might have been called appropriate concern, “if it were discovered. I wonder if you truly realize, Doctor, how very much your work frightens and angers the very people who run this city—both its politics and its business. Moore’s comment about the African witch doctor is really no joke.”

The Alienist, Chapter 6

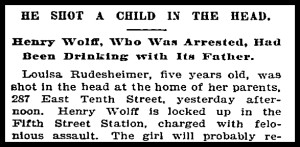

However, if you’re similar to me, you might wonder why such a sensible theory—that our experiences shape the person we become—should be considered remotely controversial, even taking into account the argument about personal responsibility before the law. My own view is that a hint towards the answer can be found even earlier in the novel following Dr. Kreizler’s assessment of Henry Wolff, a man who shot his neighbor’s five-year-old daughter in the head while she had been sitting on her father’s lap as the pair drank and argued. As Dr. Kreizler explains:

“They’ll want him to be mad, of course,” Laszlo mused, not hearing me. “The doctors here, the newspapers, the judges, they’d like to think that only a madman would shoot a five-year-old girl in the head. It creates certain… difficulties, if we are forced to accept that our society can produce sane men who commit such acts.”

The Alienist, Chapter 4

The irony, of course, is that through Dr. Kreizler’s theory of context, the definition of true mental instability—or insanity—becomes narrow indeed, and personal responsibility comes to the fore. But therein lies the problem for society: for, it is not just personal responsibility that comes to the fore—it is societal responsibility as well. As Dr. Kreizler explains to John at the conclusion of the novel, all of us, including individuals like John Beecham, the killer in The Alienist, are ultimately the products of the society in which we are raised.

“If the average person were to describe John Beecham in light of his murders, he’d say he were a social outcast, but nothing could be more superficial, or more untrue. Beecham could never have turned his back on human society, nor society on him, and why? Because he was—perversely, perhaps, but utterly—tied to that society. He was its offspring, its sick conscience—a living reminder of all the hidden crimes we commit when we close ranks to live among each other. He craved human society, craved the chance to show people what their ‘society’ had done to him. And the odd thing is, society craved him, too.”

“Craved him?” I said, as we passed along the quiet perimeter of Washington Square Park. “How do you mean? They’d have shot him through with electricity if they’d had the chance.”

“Yes, but not before holding him up to the world,” Kreizler answered. “We revel in men like Beecham, Moore—they are the easy repositories of all that is dark in our very social world. But the things that helped make Beecham what he was? Those, we tolerate. Those, we even enjoy…”

The Alienist, Chapter 46

Of course, there’s no denying that we have made progress since 1896. Psychology and psychiatry are no longer the controversial professions they once were, and journalists no longer risk dismissal or “forced internment at the Bloomingdale Asylum,” as John suggests, for reporting murders such as those described in the novel. However, in many areas of life we still prefer to deliberately ignore unpleasant truths because to do otherwise requires us to start asking difficult questions about both society and ourselves, and in this sense perhaps we really haven’t changed much since 1896, as Dr. Kreizler tries to explain to John in the opening of the novel, making The Alienist a piece of social commentary not just about society of 120 years ago, but about our society, too.

We’re all still running, according to Kreizler—in our private moments we Americans are running just as fast and fearfully as we were then, running away from the darkness we know to lie behind so many apparently tranquil household doors, away from the nightmares that continue to be injected into children’s skulls by people whom Nature tells them they should love and trust, running ever faster and in ever greater numbers toward those potions, powders, priests, and philosophies that promise to obliterate such fears, and ask in return only slavish devotion.

The Alienist, Chapter 1

“The darkness we know to lie behind so many apparently tranquil household doors.”

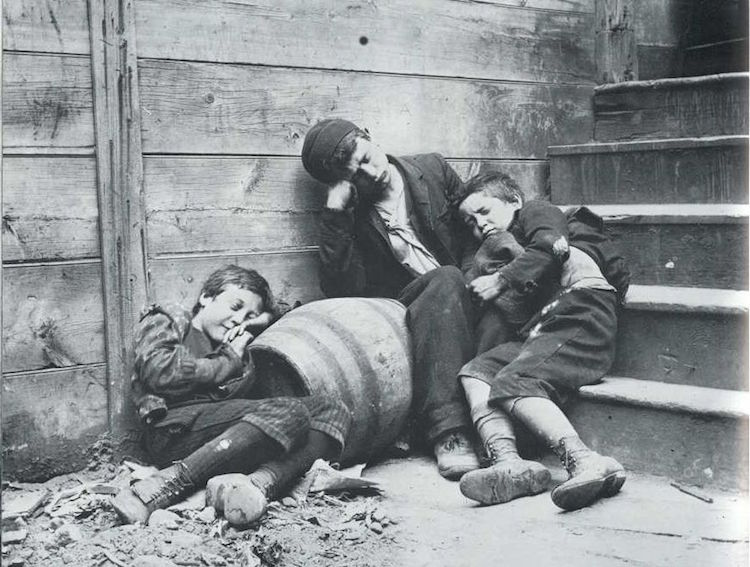

Taken in combination with psychological determinism, the themes that Dr. Kreizler alludes to in the preceding quote—domestic violence and childhood trauma—are perhaps the most important in the novel, underlying almost every element of plot and character development. Given that The Alienist is a novel about the hunt for a serial killer who targets child prostitutes, perhaps this shouldn’t take us by surprise. However, the breadth of these themes throughout the story goes beyond the obvious. From a range that spans not only the murderer and his victims, but also their families and even members of the investigative team, we witness the devastating and lasting impact that domestic violence and childhood trauma can produce, and it is an impact that can be felt as early as the first scene in the novel. In this scene, we meet Sergeant Flynn of the New York City Police Force who identifies the body of the first victim viewed by John and Dr. Kreizler, a young boy called Giorgio Santorelli, with a mixture of revulsion and amusement.

“…it was no child, this one, not if childhood be judged by behavior. Family name Santorelli. Must’ve been, oh, thirteen years old, or thereabouts. Giorgio, it was called originally, and since it began working out of Paresis Hall, it called itself Gloria.”

“‘It’?” I said, wiping cold sweat from my forehead with the cuff of my coat. “Why do you call him ‘it’?”

Flynn’s smile became a grin. “Sure, and what would you call it, Mr. Moore? It warn’t no male, not to judge by its antics—but God didn’t create it female, teither. They’re all its to me, that breed.”

The Alienist, Chapter 3

Although our narrator, John, finds Flynn’s comments repellant, Flynn’s view of Giorgio’s behavior was far from unusual for the period in which the novel is set. As John explains, children in the late nineteenth century were not yet viewed as a vulnerable population, but rather “as miniature adults, and according to the laws of 1896 if they wanted to abandon their lives to vice, that was their business—and their lookout.” However, as we are made aware through Dr. Kreizler’s considerably more enlightened attitude and methods, Giorgio lacked the freedom on a practical or psychological level to have made different choices in his life. Giorgio came from an immigrant tenement home stricken by poverty, and his father took to violently beating his son regularly from a young age for promiscuous behavior, an action that ultimately drove his son out of the home and onto the streets. The irony of this, as Dr. Kreizler points out, is that:

…if Santorelli had only been able to talk to his son and explore the roots of his peculiar behavior, he might have been able to change it. But by employing violence he turned the affair into a battle, one in which Giorgio’s very psychic survival became associated, in the boy’s mind, with the actions his father objected to.

The Alienist, Chapter 9

As we go on to discover, Giorgio’s dysfunctional home environment was typical for many of the children working in disorderly houses. For example, we see a similarly dysfunctional background for Joseph, another child prostitute John meets as a result of the investigation, who turned to prostitution as a means of survival. When John offers to find Joseph a place in Dr. Kreizler’s Institute for Children, the boy refuses his help despite his dislike of his current work. Although members of society such as Sergeant Flynn might see Joseph’s refusal as a sign that the boy wanted to abandon his life to vice, the true motivation for Joseph’s decision can once again be found in his early life.

But Joseph, orphaned since age three, had already had his fill of institutes, orphanages, and foster homes (not to mention alleyways and empty railroad cars), and nothing I said about Kreizler’s place being “different” had any effect on him. The Golden Rule had been the only home he’d ever known where he hadn’t been ill fed and beaten—repulsive as she may be, Scotch Ann had an interest in keeping her boys relatively healthy and scar-free. That fact counted for more with Joseph than anything I might say about the place’s evils and dangers.

The Alienist, Chapter 18

Perhaps the most tragic proof that the views of people like Sergeant Flynn are misguided at best is the fact that child prostitutes become victims of the serial killer in the first place. Again, it is Joseph who provides us with this insight, telling John that one of the victims, Ali ibn-Ghazi, who had originally been sold to Scotch Ann by his father, “had been saying for I guess about two weeks that she’d [he’d] found a saint. Not like a patron saint, in church, not like that—just a person who was kind, and was going to take her [him] away from Scotch Ann to live with him.” Thinking about how much Joseph reminded him of his own troubled brother who had battled alcohol, drugs, and depression before finally drowning after falling off a boat, John displays some insight into why the killer was able to convince these “fairly suspicious and skeptical children” to trust him. As he explains to Sara Howard, these children are only suspicious and skeptical “on the outside … inside, they’re praying for a real friend.”

As evidenced by the reference to John’s brother, the themes of domestic violence and childhood trauma are not limited to the victims of the killer. First, there are Dr. Kreizler’s household employees, all of whom found protection under his roof as a result of crimes that arose out of their early traumatic experiences. Cyrus Montrose, for example, had witnessed his parents being tortured and killed in the draft riots of 1863, leading him to murder a police officer during his adult years after witnessing the officer raping, beating, and verbally abusing a black prostitute. Dr. Kreizler came to his defense in court, arguing that Cyrus had “responded to the situation in the only way possible for a man with his background.” That is, he had suffered from “explosive association” (presumably Dr. Kreizler’s terminology for a symptom of what we now call PTSD) due to his early traumatic experiences that caused him to return to the moment of his parents’ death upon discovering the police officer. Similarly, Mary Palmer had murdered her father following years of sexual abuse, and Stevie Taggert had joined a violent street gang after spending his early years supporting his alcohol-dependent, opium-addicted mother.

However, when we look beyond the killer’s victims and Dr. Kreizler’s household employees, we see that “the darkness we know to lie behind so many apparently tranquil household doors” is not restricted to crime or poverty-ridden neighborhoods. Indeed, throughout the course of the novel, we come to learn that most members of the investigative team appear to have first-hand experience with some form of early trauma. Although he prefers not to discuss his childhood, referring to his family home only as emotionally repressed, John, the son of a wealthy investment banker, clearly experienced troubled relationships within his family as well, evidenced not only by his brother’s depression, drug and alcohol addiction, and subsequent death, but also by his own gambling habits, drinking habits, and emotionally-detached relationships with women. Sara, too, appears to have experienced some form of trauma or betrayal, hinted at when the team views the body of Ali ibn-Ghazi atop the roof of Castle Garden.

“But I can tell you, John—that’s a man’s work, back there. Any woman who would have killed the boy wouldn’t have…” She groped for words. “All that stabbing, binding, and poking… I’ll never understand it. But there’s no mistaking it, once you’ve… had the experience.” She chuckled once grimly. “And it always seems to begin with trust…”

The Alienist, Chapter 14

Nobody on the investigative team, however, appears to have had as much first-hand experience with early trauma than the man at the head of the team, Dr. Kreizler—a crucial point that brings us to the crux of the novel’s structure and purpose. Caleb Carr explained his motivation behind Dr. Kreizler’s creation in the afterword of the 2006 edition of the novel.

I’m not sure just when the idea of focusing on two men—both from abusive backgrounds, one of whom becomes a murderer, the other a hunter of such murderers—came to me. Perhaps it had always been there; perhaps it had been my original method of reconciling the furiously different sides of what had once been my bright but violently angry young self. Whatever the case, the most pressing need was to know why people of such seemingly similar backgrounds could turn out so differently.

The Alienist, Afterword to the 2006 Edition

Midway through the novel, we see Dr. Kreizler strongly resist a suggestion made by Sara that a woman may have played an active role in the killer’s early life. To the surprise of the investigative team, a tired and irritable Kreizler loses his temper during the meeting in which the suggestion is made, going so far as to state, “Had a woman been actively involved in this man’s life, at any point, we would not even be here—the crimes would never have happened!” Aside from producing temporary tension within the team, this outburst prompts future Private Investigator, Sara, to try to understand why the normally calm and rational Kreizler should have responded to her suggestion with such a shocking outburst. Eventually, she comes to John with the result.

“I’ve been trying all week to understand why he was sticking so stubbornly to the idea that a violent father and a passive mother raised our killer. I developed a theory, and went through the records of the Fifteenth Precinct to test it. This is what I found.”

The document was a report filed by one Roundsman O’Bannion, who, on a September night in 1862—when Laszlo was a boy of only six—had investigated a domestic disturbance at the Kreizler home. The yellowing report contained just a few details: it spoke of Laszlo’s father, apparently drunk, spending the night in the precinct house under a charge of assault (the charge was later dropped), and then of a local surgeon being brought to the Kreizler home to treat a young boy whose left arm had been badly shattered.

The Alienist, Chapter 24

It is at this point that we, along with John and Sara, realize that Dr. Kreizler has fallen prey to “the psychologist’s fallacy,” a phenomenon described by William James in his Principles of Psychology in which a psychologist gets “his own point of view mixed up with his subject’s.” Although this hurdle is overcome, the wounds from Dr. Kreizler’s traumatic childhood are exposed yet again when his housekeeper and love interest, Mary Palmer, is killed in a home invasion further on in the novel, prompting him to abandon the investigation (although, as it turns out, not fully).

“Do you know what my—father always said to me, when I was—a boy?”

“No. What?”

“That—” The voice was still scraping terribly, as if it were a labor to produce it, but the words began to come faster: “That I didn’t know as much as I thought I did. That I thought I knew how people should behave, that I thought I was a better person than he was. But one day—one day, he said, I would know that I wasn’t. Until then, I’d be nothing more than an—imposter…”

The Alienist, Chapter 36

Through these revelations, John comes to realize that his old friend is tortured by “doubts about his own judgment and abilities” as a result of his physically and psychologically abusive relationship with his father. Interestingly, we discover in the following chapter that Theodore Roosevelt was already aware of Dr. Kreizler’s past, having seen a glimpse of it during their shared Harvard days; a glimpse that prompted him, as a young man lucky enough to have had an excellent relationship with his own father, to find himself wondering at times, “How does the world look … to a young man whose father is his enemy?”

Critically, the only other man in the novel who knows what it is to have a father for an enemy is the serial killer himself, John Beecham (born Japheth Dury). As the team develop their psychological profile of Beecham, they reason that he most probably endured beatings throughout this childhood at the hand of his father as well, with—as in Kreizler’s childhood home—the violence being concealed by a façade of respectability and going unacknowledged both inside and outside the family unit. Importantly, however, it is Dr. Kreizler’s falling victim to the psychologist’s fallacy that provides one of the most important clues about why Beecham went down a dysfunctional path where Kreizler did not. When John and Dr. Kreizler visit Beecham’s brother, Adam Dury, they discover that he had been on the receiving end of abuse from both mother and father—importantly, with his mother playing the central role.

“I suppose, in a way, that I was luckier than Japheth, only because my mother’s feelings toward me had always taken the form of thorough indifference. But Japheth—it didn’t seem enough for her to merely deprive him of love. She took issue with his every action, his every move, however insignificant. Even when he was an infant, even before he had any awareness or control over himself—she’d badger him about everything he did.”

Kreizler leaned forward, offering a match that Dury took only reluctantly. “What do you mean by ‘everything,’ Mr. Dury?” Laszlo asked.

“You’re a medical man, Doctor,” Dury answered. “I think you can guess.” Smoking for a few seconds to get a good coal going in his pipe, Dury finally shook his head and grunted angrily. “The cruel bitch! Hard words, I know, for a man to assign to his own dead mother. But if you could have seen her, gentlemen—at him, always at him. And when he complained, or cried, or went into a rage over it, she’d say things so despicable that I would’ve thought them beyond even her.”

The Alienist, Chapter 34

This discovery leads us to the final collection of themes to be discussed in Part Three of the blog series: the role that mothers can play in domestic violence and childhood trauma, and the role of women in society more generally. Although these themes are typically associated with The Alienist‘s sequel, The Angel of Darkness, more frequently than they are associated with The Alienist, it would be a mistake to overlook their significance in the original novel for, as Sara pointed out to Dr. Kreizler in The Alienist, “There is more than one kind of violence, Doctor.” In addition, we will also be tackling the most important overarching theme in the novel: psychological determinism.