In recognition of our author’s birthday today, I’m taking a short break from the Alienist books for a fun diversion (for me, and hopefully for our author, too): an investigative history blog about the legendary panthers found roaming the forests of Northern Germany in his 2012 novel, The Legend of Broken. For those visitors of 17th Street who haven’t read the book, you may be wondering why a big cat is featured on the cover. If this is the case, prepare to be enlightened! For those of you who have read the book, while you will already be familiar with the legendary panthers of Davon Wood, perhaps you are less clear on what species the great cats are most likely to correspond to: Mr. Carr presented the European (or Eurasian) jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis) and the European (or Eurasian) cave lion (Panthera spelaea spelaea1) as candidate species2, but refrained from providing an argument in favour of one over the other. In the following post, we will review the evidence before us from the latest research into these ancient big cat species–including two studies published earlier this year–to put forward such an argument, and hopefully illuminate a little more of the true history of these great predators of ancient Europe.

Happy Birthday, Mr. Carr!

Who were the legendary panthers of Davon Wood?

Within The Legend of Broken we are transported back in time to the year 750 A.D., to the heart of the time period we know today as the Dark Ages that spanned the fourth or fifth century A.D. to the eleventh century A.D. The walled city of Broken, located on the peak of the Harz Mountain Range in Northern Germany, is surrounded by rugged terrain, with the Thuringian Forest (known in the novel as “Davon Wood”) bordering the region to the south. It is here that the exiles of Broken, known as the Bane, have learned to live in harmony with a variety of predators, including the most fearsome of them all–the rarely seen, solitary big cats known as “Davon panthers”.

The Legend of Broken, Chapter I:{ii:}

“What is it, Keera?” [Heldo-Bah] whispers urgently. “Wolves? I thought I heard one.”

Wolves in Davon Wood grow to extraordinary sizes, and are more than a match for any three Bane—even these three. Keera, however, shakes her head slowly, and answers: “A panther.” Veloc’s face, too, fills with apprehension, while Heldo-Bah’s shows childlike panic. The solitary, silent Davon panthers–which can reach lengths of twelve feet, and weights of many hundreds of pounds–are the largest and most efficient killers known, each as lethal as a pack of wolves and, like all cats, nearly impossible to detect before they strike. They are particularly fond of the caves and rocks near the Cat’s Paw.

When we finally do meet one of these legendary panthers, we can understand the awe with which the Bane regard these magnificent creatures. Described as reaching proportions of over nine feet from nose to tail base–twelve feet with tail included–with coat colours ranging from darkest gold to the palest gold/sand adorned with rich dark spots and stripes, presumably on the underside of the body and legs, it is not difficult to imagine why the cats achieved legendary status with their human cohabitants. Solitary hunters, they seem to have learned to survive on the deer, boar, and wild horses that roam the forest, or even to venture close to human habitation to poach shag cattle when times are tough.

However, instead of simply accepting the existence of the impressive “Davon panthers” as the Bane do, we twenty-first century readers are compelled to ask a very twenty-first century question upon meeting these remarkable creatures (or at least, this twenty-first century woman is): What are these great cats? Our author tells us in the endnotes of the novel that, “The Legendary ‘European panther’ is far more than a myth,” and goes on to cite two potential candidate species: the smaller European jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis), and the larger European cave lion (Panthera spelaea spelaea), both of which could be found over an enormous geographical range that included Northern Germany during the Pleistocene, an epoch that ended approximately 11,000 years ago. See the map below for a overview of the known geographic range of the European cave lion in and around Northern Germany (two key locations for The Legend of Broken–the city of Broken itself and Davon Wood–are also marked), including radiocarbon dates of known cave lion finds. Perhaps the reason our author refrained from providing an argument for one species over the other was due to the the fact that both the jaguar and the cave lion had their strengths and weaknesses as candidate species. Nevertheless, on the basis of very recent research, I propose that the strengths of one candidate species now outweighs the strengths of the other. So, let’s revisit the mystery and review the evidence as it currently stands.

In the case of the Davon panther, size matters.

The first and most important evidence to review in order to solve the mystery of the Davon panther relates to the sizes of the candidate species under consideration. After all, repeated descriptions of Davon panthers as having nine foot bodies from nose to tail base with weights of over 500lbs (226kg) simply can’t be disregarded, and as the European jaguar and cave lion were in entirely different size brackets, the proportions of the cats must be considered the first and most important differentiator between the two species. Perhaps the most compelling evidence in relation to size comes from a recent paper by Marciszak (2014) who conducted a comprehensive overview of size variability among European jaguars in the late Middle Pleistocene in relation to contemporary European Panthera species including the European cave lion and the European leopard on the basis of remains found for all three species collected from Biśnik Cave, Poland, in 2010.

On the basis of tooth size, previous research has established approximate body mass ranges for European jaguars of 330lbs to 418lbs (150-190kg) for males, and 220lbs to 286lbs (100-130kg) for females. Despite the fact that the jaguar from layer 19d of Biśnik Cave was evaluated to be a large, male specimen at the top of the size spectrum with an estimated body mass of 396lbs (180kg), the specimen was still strikingly smaller than contemporary cave lions found in layers 19b-d of Biśnik Cave (see the figure drawn to scale from Marciszak, 2014, below). Importantly, after reviewing specimens from almost all sites where fossil material for the European jaguar has been found, no size increase was observed for the species over its evolution, indicating that there is no reason to suppose the European jaguar would have almost doubled its maximum body mass by the period in which The Legend of Broken was set, assuming they had not died out by that period. On the other hand, the estimated weights for European cave lions do fall well within the range proposed for Davon panthers with a maximum estimated weight of up to 793lbs (360kg) for Panthera spelaea fossilis and 617lbs (280kg) for Panthera spelaea spelaea (Guzvica, 1998), although changes in size for the species throughout its evolution have recently been shown to be more complex than previously theorised.

Left to Right: European cave lion (Panthera spelaea), European jaguar (Panthera gombaszoegensis), European leopard (Panthera pardus spelaea)

Source: Marciszak (2014)

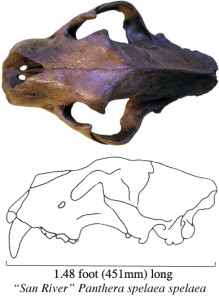

It is now generally accepted that the earliest cave lions in Europe (Panthera spelaea fossilis), which first appeared during the Middle Pleistocene, were gradually replaced by the more evolutionarily advanced Panthera spelaea spelaea during the Late Pleistocene. By once again performing comparative analyses of specimens from the palaeontologically important Biśnik Cave in Poland, Marciszak and Stefaniak (2010) observed a clear evolutionary progression from fossilis in the Middle Pleistocene, through intermediate forms that shared features with both fossilis and spelaea in the late Middle Pleistocene, to the cave lion’s final spelaea form in the Late Pleistocene. Although this evolutionary progression involved changes to cranial and dental morphology, as well as an overall decrease in body size, a more recent review of the evolution of Panthera spelaea from the fossilis to spelaea subspecies by Marciszak, Schouwenburg, and Darga (2014) includes data from a new specimen found in the San River in Poland which has shown that the evolutionary decrease in size may not have been as definitive as the 2010 study suggested.

First, one would presume that over the several thousand years between the Late Pleistocene when Panthera spelaea spelaea appears to have died out and the time period in which The Legend of Broken is set, the size of any remaining cave lions (assuming it was possible for any to have survived) would have continued to decrease, not maintain their former megafauna proportions. Indeed, by the end of the cave lion reign in Europe in the first part of the last glacial, “dwarf” cave lions with dimensions similar to medium-sized modern African lions were appearing among the European cave lion population. The finding of a fossilis-sized cave lion from a much later time period than had previously been thought possible for the Late Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea therefore helps the argument that separate lineages of cave lions may have continued to exist in Europe (see also Guzvica, 1998, for further evidence of separated lineages in European cave lion populations), which further helps the case that Davon panthers may have retained their impressive megafauna dimensions over several thousand years.

Second, it is also important to note that, like the European jaguar, the European cave lion was strongly sexually dimorphic with male skulls typically exceeding female skulls by an average of 3.93 inches (10cm) in length. Given the fact that it was a female Davon panther that was said to exceed 500lbs (226kg) in The Legend of Broken, in order for the immature male panther we meet early in the novel to grow to the correspondingly large size the female’s weight would indicate, the only possible way this could have happened is if the original megafauna proportions had been retained. Incidentally, this point also rules out the possibility that Davon panthers were relatives of the ancestors of modern African lions. Although isolated finds indicate that modern lions colonised areas of South-Western Europe as late as the Iron Age (Stuart & Lister, 2011), there is no evidence that they would have reached the proportions required for a Davon panther, nor that any separate line of modern lion would have evolved to increase in size rather than decrease in size.

To Be Continued

Although the size requirements for Davon panthers have now ruled out the possibility of the great cats having evolved from European jaguars or the ancestors of modern African lions, we are faced with the question of the panthers’ hunting and living habits. Within The Legend of Broken we are told that Davon panthers were solitary hunters rather than hunting collaboratively in prides. Does this correspond to the hypothesised hunting pattern of European cave lions? Perhaps surprisingly, recent mitochondrial DNA and bone collagen isotopic signature findings suggest that it does! We will overview this fascinating research, as well as investigating possible extinction hypotheses and the implications these have for the likelihood of Davon panther existence, in Part Two of The Legendary Panthers of Davon Wood series over the coming weeks.

Footnotes

1. Although all authors agree that the European (or Eurasian) cave lion belongs to the genus Panthera, there is less agreement about the correct species and subspecies designation in the literature. Despite DNA research showing that the cave lion was a separate species to the modern lion (see Part Two for more), many authors continue to use the leo species designation, differentiating the various cave lion types on the basis of subspecies instead (i.e., Panthera leo fossilis or Panthera leo spelaea). However, given recent DNA evidence, along with the apparent lack of cross-breeding between the various lion species during the Pleistocene, I have chosen to use the species classification preferred by Marciszak and colleagues instead. That is, Panthera spelaea fossilis and Panthera spelaea spelaea.

2. Hereafter, both species will be referred to as “European” jaguars or cave lions. The “(or Eurasian)” is implied.

References

- Barnett, R., Shapiro, B., Barnes, I., Ho, S. Y. W., Burger, J., Yamaguchi, N., Higham, T. F. G., Wheeler, H. T., Rosendahl, W., Sher, A. V., Sotnikova, M., Kuznetsova, T., Baryshnikov, G. F., Martin, L. D., Harington, C. R., Burns, J. A., & Cooper, A. (2009). Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity. Molecular Ecology, 18, 1668-1677.

- Burger, J., Rosendahl, W., Loreille, O., Hemmer, H., Eriksson, T., Gotherstrom, A., Hiller, J., Collins, M. J., Wess, T., & Alt, K. W. (2004). Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 30, 841-849.

- Guzvica, G. (1998). Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss 1810) from North-Western Croatia. Geologia Croatica, 51, 7-14.

- Marciszak, A. (2014). Presence of Panthera gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938) in the late Middle Pleistocene of Biśnik Cave, Poland, with an overview of Eurasian jaguar size variability. Quaternary International, 326-327, 105-113.

- Marciszak, A., Schouwenburg, C., & Darga, R. (2014). Decreasing size process in the cave (Pleistocene) lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) evolution — A review. Quaternary International, 339-340, 245-257.

- Marciszak, A., & Stefaniak, K. (2010). Two forms of cave lion: Middle Pleistocene Panthera spelaea fossils Reichenau, 1906 and Upper Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 from the Biśnik Cave, Poland. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, 258, 339-351.

- Stuart, A. J., & Lister, A. M. (2011). Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea. Quaternary Science Reviews, 30, 2329-2340.