Today’s final installment in the Education of Sara Howard series moves beyond our hypothetical Sara’s college years to focus on the career choices a young woman of Sara’s social class in New York had available to her in the 1880s and 1890s. As indicated at the conclusion of Part Two, the life choices female college graduates faced in the years immediately following college during the late 19th century could be stressful, with many young women forced to make difficult choices between the family claim and the social claim, the choice between marriage and a career, and the limited number of professions open to women if they did decide to pursue a career. However, a determined minority — of which Sara was one — pushed beyond societal expectations and made choices women earlier in the century would never have dared dream about. These college graduates were known collectively, in America and abroad, as “the new women”, and this is their story.

The Post-College Years

In 1896, a manual for young women was published that discussed common problems faced by female college graduates in America. Entitled “After College, What?“, the manual explained that most young women faced a “blank nothingness” at the conclusion of their college degree that left them feeling a “deep and perplexing unhappiness” until they either got married or were able to find “something [useful] to do”. Having spent four years immersed in an environment that fostered the development of independence and autonomy that was not encouraged in the typical patriarchal family home, these young women completed their college degree with a yearning to go out into the world at large and fulfill their “social claim” — a calling to use their advanced education in the same way that their brothers could; as an independent citizen with a role beyond that of wife and mother. However, upon returning to the family home following graduation, the majority of women found their parents in direct opposition, asserting the “family claim”.

However, not all parents during this period were unsupportive or asserted the family claim. As a result of her daughter’s negative experiences, Marion Talbot’s mother founded the Association of Collegiate Alumnae in 1882 for graduates from Oberlin, Vassar, Smith, and Wellesley Colleges, and Michigan, Wisconsin, Cornell, and Boston Universities to provide support that young women often lacked following graduation, and to help them through the anxiety and depression that frequently resulted from their feelings of isolation. In another example, Hilda Worthington Smith’s mother encouraged her daughter to volunteer for mission work following her graduation from Bryn Mawr College in 1910 as she felt that life as a homemaker was “too much to ask” of Hilda, and she went on to encourage her daughter to find a paying position a few years later. On the subject of her mother’s atypically supportive attitude toward entering the workforce, Hilda commented:

This I knew was a great concession, as several of her friends had warned her against letting me venture into the untried world of women’s work. Those women who did it were still thought very “advanced.” Any such excursions from home might lead to a daughter wanting her own apartment and becoming alienated from her family.

Mrs. Smith’s “advanced” views served her daughter well. Hilda went on to become Acting Dean and Dean of Bryn Mawr College from 1919 until 1922, and then Director of Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers from 1921 until 1933. Fortunately for the clever and independent Sara, it appears as though her parents views were as similarly “advanced” as Hilda’s mother’s, which we get a glimpse of in The Alienist, 78, when John Moore relates one of her post-college activities:

…right after Sara’s graduation from college, her family had gotten the idea that her education might be fully balanced by some firsthand experience of life in places other than Rhinebeck (where the Howards’ country estate was located) and Gramercy Park. So she put on a starched white blouse, a dreary black skirt, and a rather ridiculous boater and spent the summer assisting a visiting nurse in the Tenth Ward.

However, perhaps the most important thing to note, regardless of how supportive or unsupportive families were, is that for almost all of the young women who belonged to the pioneering generation of female college graduates in the late 19th century, parental attitudes and family ties were the key factor in the decisions they made about what to do following graduation. Although there were rare college graduates who decided to find a means of supporting themselves in order to live completely independently immediately following graduating in order to avoid the need to consider the family claim at all, these women were the exception rather than the rule — and given her supportive family and the influence they had on her decision to gain firsthand experience as a visiting nurse in the Tenth Ward, it seems safe to say that Sara would not have been one of them.

The Marriage versus Career Dilemma

Nevertheless, Sara would have still faced societal pressure to marry in the years following her college graduation despite her family’s supportive attitude. Even though women’s colleges in the Northeast were established to provide young women with intellectual training equivalent to what was offered at nearby prestigious institutions such as Harvard and Yale, most women’s colleges and almost all of the coeducational Universities had never aimed to steer women away from what was traditionally seen as women’s proper sphere (see Part One). As described in Part Two, the majority of these institutions aimed to provide young women with either advanced training in teaching or to produce “educated wives and mothers”. The girls who attended the colleges, however, seem to have had other ideas. One 1897 graduate from Wellesley commented that “happy domesticity” was “a state often looked upon with scorn in our ambitious college days”.

If the notion that women only had the option to choose marriage or a career following graduation, with no third option for marriage and a career, seems too rigid or implausible to the modern reader, it must be remembered that for the whole of the 19th century — almost without exception — married women could not pursue a career. Even teaching, a profession long considered acceptable for women who had to work for financial reasons, could only be pursued by single women or widows; upon a woman’s marriage, her position at a school had to be vacated. This was true of institutions that the modern reader might think would have been sympathetic to the an ambitious woman who wanted to “have it all” as well. Wellesley College, for example, was a women’s college with an all-female faculty, but they also required their academic staff to step down from their positions on the occasion of their marriage. Unless a woman was lucky enough to have a supportive husband who she could work alongside of, it truly was a case of making a choice between one or the other for the majority of women. Only 10% of graduates from Smith College between 1879 and 1888 had any form of paid employment following marriage.

Although these women were perceived relatively positively in the press at the time, largely due to a corresponding decline in perceptions of traditional Victorian notions of “duty” and marriage — one 1888 commentator stated, “The words ‘old maid’ have recently been shorn of their terrifying power; they have been revered in contrast with the words ‘unhappy wives’.” — fear that the social classes they belonged to would dive into an irreversible decline was sparked at the turn of the century as birth rates had, in fact, dropped sharply. Reflecting this fear, and understanding that education had been the tool that enabled the spinsters of the 1890s to choose their newly independent lifestyles, G. Stanley Hall, a notable psychologist and President of Clark University, published a work on education in 1904 in which he claimed that intellectual women were “functionally castrated” and that biological psychology “dreams of a new philosophy of sex which places the wife and mother at the heart of a new world and makes her the object of a new religion and almost of a new worship, that will give her reverent exemption from sex-competition and reconsecrate her to the higher responsibilities of the human race…” Hall’s ultimate thesis was that education should only be used to train women to regard matrimony as her “one legitimate province”. Views such as these, which were by no means isolated, highlight just how accurate Sara’s comments to Stevie in The Angel of Darkness, 368, really were:

“…all we do know is that the message girls get when they’re growing up — especially in corners of the world like this one — is that if you want to do something with your life other than raise children, not only will your road be difficult, but you’ll never really be a woman. You’ll just be a female, of some indefinite and not very appealing type. A harlot, maybe. Or perhaps a servant. Or, if you join a profession, a detached functionary. Whatever the case, underneath it all you’ll be a cold, unfeeling aberration.” With an angry flick of her finger, Miss Howard showered the road below us with sparks from the burning tip of her cigarette. “Unless you want to be a nun, of course — and even they don’t always get away with it… A man can be a bachelor, and still be a man — because of his mind, his character, his work. But a woman without children? She’s a spinster, Stevie — and a spinster is always something less than a woman.”

Female college graduates, it would seem, agreed with Kate. In a review of occupations and lifestyle choices of Wellesley College’s class of 1897, 46% of graduates classified as “working daughters” who never married and instead remained living at home with family while pursuing a career, 19% classified as “experimenters” who pursued a career following college graduation before eventually marrying, and 6% classified as “independents” who pursued a career while living independently away from the family home. A minority — only 14% — married without having tried their hand at any from of career first. Similarly, in a review of marriage statistics for graduates from Vassar College, only 16.3% of graduates from the classes of 1892 to 1896 married within five and a half years of graduation, although approximately 50% did eventually marry at some stage in their life (with the majority of these marriages — 63.2% — taking place between the relatively high ages of 27 to 37 years, presumably following time spent pursuing a career).

Careers for College Educated Women in the Late 19th Century

Even though their education provided them with the skills to enter almost any professional field open to men, many of the careers college educated women pursued remained those that had traditionally been seen as women’s professions, with teaching the most common choice: 38% of Smith College students who graduated between 1879 and 1888 had taught in schools at some point in their life. The rate of teaching was even higher for the less well-to-do students from Mount Holyoke College who graduated between 1890 and 1909: between 75% and 82% of students who entered some kind of occupation following graduation (82% of the total graduate pool) pursued teaching as a career. A considerably smaller percentage of Smith graduates between 1879 and 1888—11.5%—went into “professional” fields such as medicine, academia (professors or college deans), and architecture.

Perhaps the traditionally male-dominated fields that made the greatest gains for women in the late 19th century were in academia. Due to the limited choices of profession for more intellectually-inclined young women during this period, a number who had supportive families decided to pursue graduate study and complete their PhD. Many of the established “hard sciences” were not welcoming to female graduate students, but emerging fields such as psychology were more open to the idea. Nevertheless, many young women who chose this path delayed their entry into doctoral study. First, a number encountered difficulties finding large research Universities that would accept female graduate students without placing unreasonable restrictions on their study (e.g., being unable to attend classes with male students). Second, it was not clear in the early days what women could do with a doctoral degree and families feared it would make their daughters less marriageable. Most women who stayed in academia following the conferral of their PhD ended up having to accept less prestigious positions at women’s colleges as tenure track positions at large research Universities frequently excluded women or confined them to lower ranks. Third, if the field they wished to study fell into a science such as psychology, the personality traits required to succeed such as “toughness, rigor, competitiveness, dominance, and rationality” were thought unbecoming in women: “women scientists were … caught between two almost mutually exclusive stereotypes; as scientists they were atypical women; as women they were atypical scientists”. However, not all women wished to confine themselves to the sciences, or an academic or teaching position, as Sara tried to explain to John in The Alienist, 44:

I could only laugh. “Sara — with all the professions open to women these days, why do you insist on this one? Smart as you are, you could be a scientist, a doctor, even –”

“So could you, John,” she answered sharply. “Except that you don’t happen to want to. And, by way of coincidence, neither do I.”

Conclusions

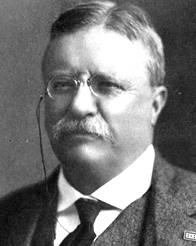

Now that we have reached the conclusion of the Education of Sara Howard series, it should be clear that ambitious females in the late 19th century had a lot to contend with if they wanted to break away from the women’s sphere of the early-to-mid-19th century. Although events such as the Civil War had allowed women to make the first moves into the male sphere outside the home, the key to realising their ambitions had ultimately lain with the improved educational opportunities that became available from the late 1860s onwards. Advanced education allowed many young women to experience autonomy and independence for the first time in their life, and opened the doors to the possibility of pursing a true career. Even though career options post-college in the late 19th century were still limited, the generation of “new” spinsters who were prepared to defy societal expectations and choose a career over marriage, along with a growing number of forward-thinking men such as TR, helped to improve women’s options in the workplace further. As Dr. Kreizler assured Sara in The Angel of Darkness, “Change is coming, however, Sara — though I grant you, it approaches with glacial speed. But it will come. You shan’t be idealised for ever.”

Sources

- Amneus, C. (2003). A Separate Sphere: Dressmakers in Cincinnati’s Golden Age, 1877-1922 ; with essays by Anne Bissonnette, Marla R. Miller, and Shirley Teresa Wajda. Texas, United States: Texas Tech University Press.

- Antler, J. (1980). “After college, what?”: New graduates and the family claim. American Quarterly, 32(4), 409-434.

- Freeman, R., & Klaus, P. (1984). Blessed or not? The new spinster in England and the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Journal of Family History, 9(4), 394-414.

- Gordon, K. (1905). Wherein should the education of a woman differ from that of a man? The School Review, 13(10), 789-794.

- Gordon, S. H. (1975). Smith college students: The first ten classes, 1879-1888. History of Education Quarterly, 15(2), 147-167.

- Hewes, A. (1911). Marital and occupational statistics of graduates of Mount Holyoke College. American Statistical Association, 12(96), 771-796.

- Newcomer, M., & Gibson, E. S. (1924). Vital statistics from Vassar College. American Journal of Sociology, 29(4), 430-442.

- Scarborough, E., & Furumoto, L. (1989). Untold Lives: The First Generation of American Women Psychologists. New York, NY, United States: Columbia University Press.

- Schwager, S. (1987). Educating women in America. Signs, 12(2), 333-372.

- Zacks, Richard. (2012). Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York. New York, NY, United State: Anchor Press.