Welcome to the fourth and final part of the “Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street?” series. Over the course of this series, we’ve overviewed the origins of Stuyvesant Square from its earliest days through to the 1840s (Part One), read about the district’s most active period of development in the 1850s through to the early 1880s (Part Two), and learnt more about the enormous influence one reforming rector at St. George’s Church had on the district in the late 1880s and 1890s (Part Three). In this final blog of the series, we will be discussing why Caleb Carr might have selected the location as the home for his protagonist before briefly touching on how the district continued to develop in the early 20th century.

Why might Caleb Carr have chosen 283 East 17th Street as Dr. Kreizler’s residence?

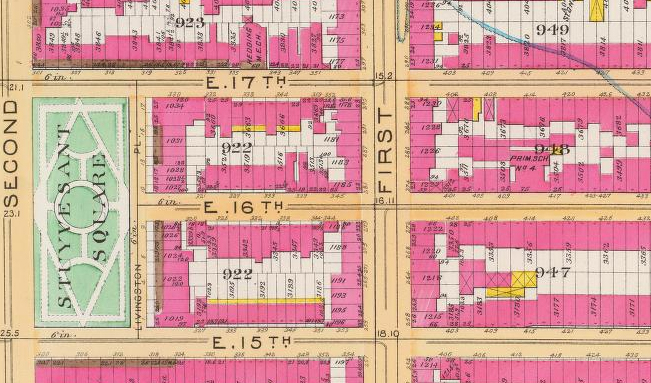

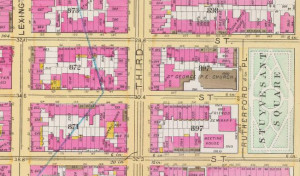

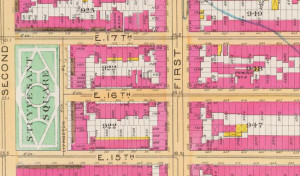

I feel it’s important to start this blog by stating the obvious: as I am not the author, I can only hypothesize as to why he may have chosen the fictional address of 283 East 17th Street as the home for his protagonist–and, yes, it is a fictional address. As can be seen in the 1891 maps of the district to the right and below, the section of 17th Street overlooking the park that was described as the location for Doctor’s home is bisected by Second Avenue. On the western side of Second Avenue, lot numbers ended at No. 251 (originally the Hamilton Fish mansion, later turned New York Lying-In Hospital; see below), while on the eastern side of Second Avenue, lot numbers started again at No. 301. Nevertheless, by examining the district’s composition in the 1890s, as well as overviewing the proximity of the neighborhood to other locations of importance in the Alienist books, we can start to theorize about why Caleb Carr might have selected the location. In addition, as Mr. Carr had his own connections to the district in his youth, it seems likely that this may have also played a role in his choice of Stuyvesant Square as the Doctor’s home.

The proximity of Stuyvesant Square to medical establishments

Medical establishments have played a key role in Stuyvesant Square’s development from the neighborhood’s earliest days. One of the first institutions to be established in the district was the New York Infirmary on Livingstone Place in 1864. Founded in 1853 by Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to receive a medical degree in the United States, the Infirmary was originally located near Tompkins Square before it moved to Stuyvesant Square eleven years later. The Infirmary offered a variety of health services for women including a dispensary, nursing courses, and even a women’s medical school. It was also one of the first institutions that conducted investigations into patients’ living conditions.

St. Andrew’s Convalescent Hospital, opened in 1890, was the second medical institution to be established in the Square and also provided health services for women. Run by the Sisters of St. John the Baptist Foundation who had already established a mission in the neighborhood (see Part Two), the hospital operated out of two of the Anglo-Italianate row houses located at Nos. 211 and 213 East 17th Street, and offered free health services for up to 35 women at a time. In the early 20th century, St. Andrew’s was visited by Theodore Roosevelt’s cousin, Kate Shippen Roosevelt, who was a New York matron. She reported that the hospital accepted “women, children and girls of good character who need care, nursing and rest or who are recovering from acute illnesses, but are not ill enough to be admitted to a regular hospital,” and went on to report that, “All suitable cases [were] received promptly with or without payment.”

The third medical institution to be established in the district also catered for women and was featured in The Angel of Darkness as one of Libby Hatch’s places of employment. The New York Lying-In Hospital moved to No. 251 East 17th Street in 1894 after John Pierpont Morgan, whose activities at St. George’s Church (overviewed in Part Three) had already established him as a man of important philanthropic influence in the neighborhood, purchased the former Hamilton Fish mansion which stood at the location. The hospital functioned out of the original mansion for three years until Morgan generously donated $1,000,000 in 1897 to demolish the house and construct a purpose-built maternity hospital in its place. The original mansion had previously been able to provide care for up to 32 patients at a time, and although it had incorporated operating and delivery rooms, the purpose-built hospital that opened in 1902 was far superior. Still standing today (although no longer a hospital), the new building provided care for up to 186 patients and contained a number of operating theaters, an amphitheater, lecture rooms, and even a museum. Although Stuyvesant Square was still a reasonably affluent neighborhood in the 1890s, the district was bordered by tenements (see Part Three) and the hospital therefore accepted both paying and charity cases. The hospital’s large intake of charity cases eventually resulted in financial hardship, forcing the hospital to move to another location in 1932.

Although establishments such as the Lying-In Hospital played an important role in both the district and the Alienist books, Stuyvesant Square’s close proximity to Bellevue Hospital would have been of greater importance for the character of Dr. Kreizler given his area of specialty. Founded in 1736, the hospital moved to its current location bordered by the East River, First Avenue, East 26th Street, and East 28th Street in 1794. In Stuyvesant Square’s earliest days, its close proximity to Bellevue was the primary reason why the stretch of Third Avenue passing through the neighborhood was lined with lamps in the early 19th century, even though it was technically not part of the “lamp district”. Given that Bellevue doubled as a penitentiary and almshouse in its early years, the hospital’s close proximity to what would later become a genteel residential district was considered a threat to public safety, and the lamps provided a measure of security. The penitentiary and almshouse continued to be run alongside the hospital until mismanagement and high mortality rates prompted reorganization in the 1840s. During this time, Bellevue’s male prisoners were sent to the new penitentiary on Blackwell’s Island, female prisoners were sent to the Tombs, and psychiatric patients were sent to the new asylum on Blackwell’s Island.

As a result of Bellevue’s reorganization, the hospital’s mortality rate decreased significantly in the years that followed, and its facilities were further expanded mid-century to include an outpatient dispensary, reception hospital on Canal Street, auxiliary hospital uptown, as well as a number of medical schools, making it the largest hospital in New York until the late 20th century. It was also the first hospital in the United States to develop an ambulance service in 1861. Even though the hospital no longer held psychiatric patients in a long-term capacity (the Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital wouldn’t be established until 1931), an Insane Pavilion located near First Avenue and East 26th Street was constructed for the hospital in 1879 so that individuals who committed violent acts could be held for observation until they were able to be assessed and sent to a more appropriate institution. Given the Doctor’s profession as a psychiatrist and expert witness, close proximity to Bellevue would therefore have been very convenient. Indeed, the first scene in which we meet Dr. Kreizler during The Alienist is at the Insane Pavilion of Bellevue.

Stuyvesant Square’s proximity to the courts of law

Also related to the Doctor’s work as an expert witness, Stuyvesant Square’s close proximity to the city’s various courts of law would have also proved to be a convenience. One such court of law that features in The Angel of Darkness is Jefferson Market Courthouse, located on the corner of West 10th Street and Sixth Avenue (now Avenue of the Americas) in nearby Greenwich Village. Established in 1877, the large complex of High Victorian Gothic style red brick buildings that the courthouse occupied also included a market (the original Jefferson Market had been razed to make way for the new structure), a firehouse, and a small jail. The third district civil court occupied the second level of the building, while the second district police court occupied the first level. Other courts of law that the Doctor would likely have attended through his work include the Tweed Courthouse on Chambers Street and the Essex Street Courthouse on the corner of Ludlow Street, both of which are located only a relatively short distance from the Doctor’s home.

Cultural influences in and around Stuyvesant Square

Throughout the novels we are made aware that in addition to Dr. Kreizler’s medical and scientific colleagues, he appears to have moved in a variety of creative circles as well, and counted artist Albert Pinkham Ryder and architect Richard Morris Hunt among his friends. Although the poor cousin of nearby Greenwich Village in terms the number of creative personalities who called the Square home, the district was located well within walking distance of The Players at Gramercy Park, a club established in 1888 for men active in literary and artistic circles, and attracted the residence of a number of writers, theater people, artists, and musicians in the 1890s which may have held appeal to a character like the Doctor. Between 1892 and 1895, the Square was also home to noted composer Antonin Dvorak who wrote the New World Symphony and his famous Cello Concerto while living at No. 327 East 17th Street. Today a memorial statue of Dvorak can be found in the eastern half the park.

In addition to the district’s creative influences, Stuyvesant Square was also located very close to Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) that was home to a large population of German immigrants throughout the 19th century and spanned 400 blocks around Tompkins Square. Although Kleindeutschland was largely composed of poor immigrant families by the 1890s with prosperous German-Americans moving to more affluent neighborhoods further north, Stuyvesant Square’s close proximity to the area resulted in a number of German families moving into the district in the late 19th century, presumably to retain their ties with the German cultural center of the city. Although it doesn’t appear within the books that the Doctor was desirous to involve himself in any of the politically active German-American clubs around the neighborhood, he may have enjoyed visiting some of the district’s local restaurants and beer gardens such as Scheffel Hall. Indeed, one of the team’s meeting places within The Alienist is Brübacher’s Wine Garden, located within walking distance of the Doctor’s home.

The author’s previous experience with the district

Perhaps more important than any of the preceding points, however, is the fact that Caleb Carr had considerable experience with the neighborhood during his youth. As mentioned in Part Two, Mr. Carr attended high school at Friends Seminary on East 16th Street which would have afforded him a fairly intimate knowledge of the neighborhood. Two interviews from 1994 also indicate that Mr. Carr lived at Stuyvesant Square for a number of years when he was in his 20’s, further cementing his familiarity with the district and the surrounding area. This latter point is consistent with Mr. Carr’s chosen residence for The Alienist’s narrator, John Moore. Like John, Mr. Carr lived with his paternal grandmother on Washington Square for a number of years as well.

Related to this, given that Stuyvesant Square’s close proximity to other key locations in the Alienist books would have also played a role in making the neighborhood an appropriate choice for the Doctor, it’s worth noting that many of these locations appear to have been chosen on the basis of the author’s prior experience living in lower Manhattan as well. Take, for example, Mr. Carr’s selection of 808 Broadway as the team’s headquarters, a choice he explained during January’s New York Times book club chat:

I wish I had ever lived in that building! I was there only in my mind, from childhood through college: the loft they are meant to use is the one on the top floor facing the Church. It always seemed to me, as a boy, the most wonderful and serene place imaginable, so of course, given my perverse nature, it was the perfect place in the book to discuss the grimmest subjects imaginable!

Conclusions

And with that, we’ve finally reached the end of the “Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street?” series. Although we’ve really only scratched the surface on some of the more interesting residents and properties around Stuyvesant Square, if you have read this entire series hopefully you will have concluded that this is a small district with an interesting history, both during the period in which the Alienist books are set as well as during earlier decades, and it’s easy to see why Caleb Carr might have selected the location for Dr. Kreizler’s home.

For anybody who may be wondering what happened around Stuyvesant Square during the years immediately following the 1890s, with the New York Lying-In Hospital and the New York Infirmary already occupying large areas around the Square in the early 20th century, the arrival of the Beth Israel Medical Center in 1921 firmly cemented the neighborhood as a hospital district, a reputation it maintains to the present day. The religious institutions around the district also remained active over the years, although not quite at the levels reached in the late 19th century, and additional schools were established in the area over the years as well. Despite the changes these various medical, religious, and educational institutions made within the district over the years, the neighborhood remained residentially conservative as it entered the 20th century, as the following quote from a New York Times article in 1899 indicates:

Even among those who know their New York pretty well, there are some persons to whom the neighborhood of Stuyvesant Square is not at all familiar ground. Yet here, for those who prefer the old to the new, is one of the most attractive sections of the city. The past quarter of a century has touched it very lightly, and in this general vicinity there are not a few landmarks still existing of the New York of fifty years ago. The commodious and dignified residences on Second Avenue from Tenth to Twentieth Street would seem more properly placed in a homelike, provincial town than in modern New York. Many of them belong to substantial German residents. On the corner of Fourteenth Street is the house of ex-Senator William M. Evarts; not far away in the square the families of Fish and Rutherford, Stuyvesant and De Voe, still live.

Although Stuyvesant Square went through ups and downs over subsequent decades as different groups ranging from Tammany Hall politicians to immigrant populations moved in and out of the neighborhood over the course of the 20th century, many of the families that still live in the area go back multiple generations, and the district has retained its reputation as a serene and close-knit community up to the present day.

Selected Sources

- Authors At Home: Richard Henry Stoddard and Elizabeth Drew Barstow Stoddard in East Fifteenth Street. (1899, Jun 24). The New York Times, p. BR412.

- Capuzzo, Mike. (1994, Aug 25). Author Feeds His Romantic, Sinister Image. Philadelphia Inquirer.

- City of New York Landmarks Preservation Commission. (1975). Stuyvesant Square Historic District Designation Report.

- Dr. W. S. Rainsford Dies in 84th Year. (1933, Dec 18). The New York Times, p. 19.

- Dunning, Jennifer. (1982, Mar 12). Exploring the Historic Stuyvesant Square Area. The New York Times, p. C1.

- Garner, Craig G. (2010, Nov 24). Lost Hospital – The Lying-In Hospital of New York at Second Avenue. Hospital Stay: Health Care Made Simple.

- Goncharoff, Katya. (1985, Apr 21). If you’re thinking of living in: Stuyvesant Square. The New York Times, p. R9.

- Guilds’ Committee for Federal Writers’ Publications, Inc. (1939). New York City Guide. United States: Best Books.

- Hazard, Sharon. (2013, Jan 14). Kate Roosevelt visited St. Andrew’s Convalescent Hospital on Stuyvesant Square. The Gang From West End.

- Homberger, Eric. (2005). The Historical Atlas of New York City. New York, NY: Holt Paperbacks.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. NY: Yale University Press.

- Knights, Edwin M. (Issue 2). Bellevue Hospital. History Magazine.

- Miller, Tom. (2010). The 1860 Friends Meeting House – Stuyvesant Square. Daytonian In Manhattan.

- Mr. Morgan’s Gift. (1897, Jan 15). The New York Times, p. 6.

- New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. (2011). Hedding Methodist Episcopal Church – New York City. NYC Organs List.

- Purdy, Matthew. (1994, May 19). On the Lower East Side with: Caleb Carr; Writing to Flee the Past. The New York Times.

- Rainsford, William S. (1922). The Story of a Varied Life; An Autobiography. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Company.