Welcome to the second post in the “Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street?” series. In Part One, we started to outline the historical context of the square, starting with the park as a gift from the Stuyvesant family before moving onto the development of the district in the 1840s with the arrival of the neighborhood’s first residents and religious institutions. In Part Two, we continue to track the development of the district from the 1850s through to the 1880s, before we reach the critical period for the books, the 1890s.

A district under construction in the 1850s and ‘60s

Although building in the district had begun in the 1840s with a number of unpretentious Greek Revival style residences, store-residences, and churches constructed around Peter Gerard Stuyvesant’s generously donated tract of parkland, the steady migration northward of New York’s middle and upper classes during the mid-19th century meant that the 1850s and ‘60s represented the greatest period of growth for the district. While the wealthiest members of the upper classes were building newly fashionable Italianate brownstone mansions and French chateaux in Fifth Avenue, districts such as Stuyvesant Square were attracting a burgeoning successful merchant class who also wanted to make their mark on the city with still fashionable but less extravagant late Greek Revival, Italianate, Anglo-Italianate, and transitional style row houses.

Unlike the previous decade in which most of the properties built in the Stuyvesant Square district were modest three-story brick dwellings, the 1850s and ‘60s saw the construction of predominantly four-story brick and brownstone homes. Most lots were purchased or leased during this period by a small number of builders on the condition that a suitable residential property would be erected on the land before being sold on to their first owner-occupants. As an example, Robert Voorhies, a prominent builder in the district, purchased eight lots on East 16th Street for $16,800 in January of 1852, developed all eight lots by November of the same year, and sold the completed homes for $11,000 each by the end of the year, providing him with a healthy profit and the district with eight new residents.

One notable owner-occupant of a property in the 1852 row that Voorhies built on East 16th Street was the author and publisher George Palmer Putnam (not to be confused for his grandson and namesake who was also a notable author and publisher), who had been a partner in the New York publishing house, Wiley & Putnam, before establishing his own publishing house, G. Putnam Broadway, in 1848. Although Putnam maintained a minor literary career of his own, writing a number of volumes including Chronology; or, an Introduction and Index to Universal History, Biography, and Useful Knowledge and Manners and Customs of the United States, With Portraits, he was most well-known as one of the leading American publishers in the 19th century. By 1868, he had published upwards of 300 original volumes by classic American authors and poets including Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Edgar Allan Poe, and William Cullen Bryant, and the year following his house purchase on East 16th Street, he was named the official publisher for the New York World’s Fair. In addition to publishing, he was also editor of a monthly periodical, The Booksellers’ Advertiser, founder of Putnam’s Magazine (which later merged with Scribner’s Monthly), and in later years was also a founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In addition to Putnam, other original owner-occupants of the same row of houses on East 16th Street included importer Walter W. Webb, “gentleman” Antonio Franchi di Alfaro, and coal merchant Franklin Randolf, vividly demonstrating the diversity of the neighborhood during this period. Further evidence for the Stuyvesant Square district’s diversity can be observed in the professions of other owner-occupants in neighboring streets during the early 1850s. East 15th Street contained the home of bookseller Mahlon Day, shipchandler Lewis L. Squires, lime merchant David B. Keeler, and tea merchant Theodore Crane, while East 17th Street was home to grocer Nelson Sherwood, grocer Samuel Schiffer, merchant William H. Smith, coppersmith Rufus Brooks, broker James McKibbon, importer Juste Lanchantin, tailor Samuel Joyce, and a relative of the Stuyvesant family, Margaret Nielson.

Although the childless Peter Gerard Stuyvesant had drowned at Niagara Falls in 1847 with no direct descendants to inherit his remaining property, he had left the bulk of his estate to his nephews Gerard Stuyvesant and Governor Hamilton Fish (son of Nicholas Fish and Elizabeth Stuyvesant), along with his 5 year old grand-nephew Stuyvesant Rutherford on the condition that his name be changed to Rutherford Stuyvesant. In consequence of this, various members of the extended Stuyvesant family retained property in the neighborhood throughout the 1850s and ‘60s, although this was primarily for investment and rental purposes. Nos. 228 to 234 East 18th Street, for example, were built by Lewis Rutherford, acting on behalf of his son, Rutherford Stuyvesant, and were originally rented out. Upon coming of age in the late 1860s, Rutherford Stuyvesant leased his remaining undeveloped lots, which were also the last empty lots in the district, on the condition that within one year “a substantial brick or stone dwelling three or more stories high … but not a tenement house … equal in height and quality and style to the adjacent houses” would be erected. Consistent with his stipulations, a row of elegant late Italianate four-story brick houses, Nos. 220 to 226 East 18th Street, were completed by September 1869.

Also constructed in 1869 by Rutherford Stuyvesant was a building that came to be known as “Stuyvesant’s Folly” by a cynical public, the district’s first apartment house at No. 142 East 18th Street between Third Avenue and Irving Place. According to The New York Times, it was thought that “no family … would want to share its home with another family”. Once erected, however, the brownstone apartment house was an immediate success, and it was almost always filled to capacity for the 88 years that it stood in the location. The first inhabitants of the apartments ranged widely and included a number of writers and theatre people along with the first stenographer of the Stock Exchange, George Riker Bishop, and the widow of General George Armstrong Custer. In later years, notable short-term visitors to the building apparently included Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Theodore Dreiser, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, and a son of Czar Alexander II of Russia.

Other religious influences arrive at Stuyvesant Square in the 1860s and ‘70s

Although St. George’s Episcopal Church and the Hedding Methodist Episcopal Church, both discussed in Part One, helped to shape the character of Stuyvesant Square in the neighborhood’s early years, they were not to be the only religious influences in the district during the mid-19th century.

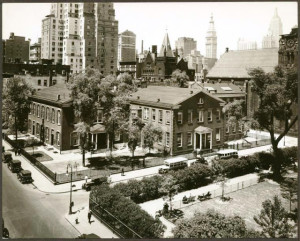

It is somewhat ironic that two of the most well-known buildings in Stuyvesant Square, the Friends Meeting House and Friends Seminary on Rutherford Place located between 15th and 16th Streets, are prominent Quaker sites. The original owner of the land, Governor Peter Stuyvesant, openly condemned the newly arrived Religious Society of Friends, known as Quakers, in 17th century New Amsterdam, and in 1656 forbid citizens to “admit, lodge, or entertain … any one of the heretical and abominable sect called the Quakers.” Although Stuyvesant also prohibited “conventicles”–secret meetings for religious worship–in order to prevent the Quakers from meeting underground, and fined, arrested, or banished any individuals who were found at such meetings, the Friends community continued to grow in the late 17th century and were worshipping in the open by 1681. Although prejudice against the group continued during subsequent years, they were eventually granted equal civil rights as other British subjects by 1734.

Friends Seminary was founded in 1786 on Pearl Street as Friends’ Institute through the $10,000 bequest of Robert Murray, a wealthy merchant in New York, in order to provide Quaker children with a “guarded education”. When the school’s attendance grew, it moved to a larger site on Elizabeth Street in 1826 where it stayed for the next 34 years until its final move to Stuyvesant Square in 1860. The Quakers involved with the Seminary had been part of the breakaway Hicksite Friends movement that favored traditional Quaker values, and placed emphasis on the “Inner Light” as a source of direct inspiration. The Hicksite breakaway took place largely as a result of Orthodox Quakers developing a revived interest in the Bible thanks to the Evangelical movement that had swept through a number of different Christian denominations in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The schism between the two branches had grown so significantly by 1827 that the Hicksites voluntarily withdrew from the Friends Yearly Meetings, and started holding their own meetings at the Hester Street Meeting House until 1861 when they moved to the newly completed Friends Meeting House in Stuyvesant Square. The builder and designer of both Friends Seminary and the Meeting House on Rutherford Place was Charles Bunting, a member of the society, and the emphasis on the simple and traditional Hicksite values can be seen in the conservative style of the buildings through their combination of Federal and Greek Revival elements, both styles that had achieved their height in popularity more than 20 years before the buildings were constructed in 1860 and ’61. Although neither building is mentioned in the Alienist books, the school’s notable alumni includes a prominent historical figure in the books, Theodore Roosevelt, along with the Alienist books’ author, Caleb Carr, and will therefore be discussed again briefly in the final blog of this series.

In addition to Friends Meeting House and Friends Seminary, the land for a fourth religious institution in the district was purchased by Helen Folsom from Rutherford Stuyvesant in the late 1870s for a token ten dollars on behalf of a German Mission of the Holy Cross, the St. John the Baptist Foundation. The Foundation built their mission in two sections at No. 231-235 East 17th Street. The first and larger section was built in 1877 by architect E. T. Littell in Victorian Gothic style, and the second section was built in a complementary style in 1883 by an architect who had trained in Littell’s office, Charles Coolidge Haight. The Foundation’s mission was to provide spiritual, educational, and charitable relief for the German immigrant population that lived in tenements located near the Stuyvesant Square district. The Sisters of the Foundation ran a private girls’ school, offered Bible classes and related spiritual activities, and organized donations of living essentials for any individuals they perceived as the “deserving poor”. Although not the first religious organization in the district, the St. John the Baptist Foundation was one of the earliest to engage in such wide-ranging charitable activities, an element that would come to define the district’s character in later years.

Stuyvesant Square gets its second apartment house and first architect-designed private residence in 1883

Not long after the St. John the Baptist Foundation was established, the district gained its second apartment house which was also located on East 17th Street (No. 223-225), a seven-story French Renaissance style building with an elaborately carved stone ornament facade known as the St. George Residence. Constructed in 1883, the St. George had two spacious apartments located on each of its seven floors, with an elevator installed to transport residents to the upper floors. This apartment block format was popular during this period, and a similar block of bachelor flats located at No. 34 Gramercy Park was included as a location in The Angel of Darkness to provide John Moore with a residence following his grandmother’s death. Coincidentally, No. 34 was also built in 1883 however unlike the St. George, it was a larger brownstone building and consisted of 27 apartments in all, each containing between 7 and 11 rooms. No. 223-225 East 17th Street still stands today, although its apartments have been split into single rooms in order to operate as the current Hotel Seventeen. (Fun fact: Hotel Seventeen was also used in Woody Allen’s Manhattan Murder Mystery as the facade for the fictitious ‘Hotel Waldron’.)

In addition to the St. George Residence, the first architect-designed private residence was also constructed in Stuyvesant Square in 1883. The four-story brick and brownstone townhouse at No. 245 East 17th Street was designed for Sidney Webster by famed architect Richard Morris Hunt (who received a brief cameo in The Angel of Darkness as a friend of Dr. Kreizler’s) in modified French Renaissance style and is currently the only New York City residence designed by Hunt that is still standing. Sidney Webster came to acquire the land for the property through his marriage in 1860 to Hamilton Fish’s eldest daughter, Sarah, who he met while working as private secretary to President Franklin Pierce; at the time that Sidney Webster was introduced to Sarah, Hamilton Fish (one of Peter Gerard Stuyvesant’s aforementioned nephews who had inherited much of his estate) had been elected United States Senator from New York, having left his position as 16th Governor of New York in 1850. Following his position as private secretary to President Pierce, Webster went on to a successful law career in New York City before becoming a director of the Illinois Central Railroad. In addition to their townhouse in Stuyvesant Square, the Websters also maintained a country home in Newport, Rhode Island.

To Be Continued

With construction in Stuyvesant Square largely completed by the mid-1880s, in Part Three of the blog series, we will learn about some of the big personalities that came to shape the character of the district in the critical decade for the Alienist books, the 1890s.