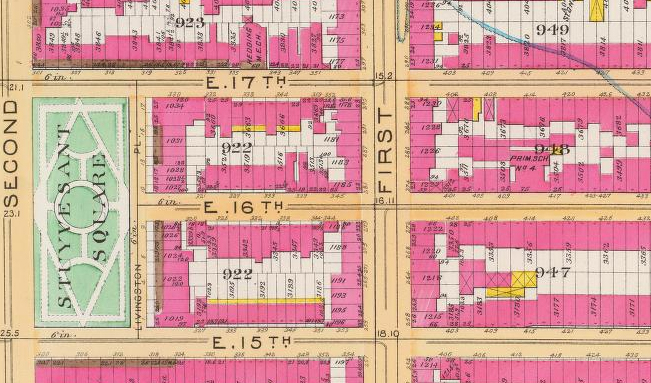

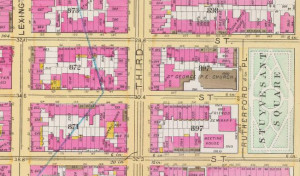

View Part One, Part Two, Part Three, and Part Four of the Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street? series.

Welcome to Part Three of the “Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street?” series. In Part One, we overviewed the early development of Stuyvesant Square from its rural origins to the start of construction in the district in the 1840s. In Part Two, we overviewed the greatest periods of growth in the district, the 1850s to early 1880s, and learnt about the first owner-occupants of the houses in the neighborhood, many of whom were successful merchants, along with the tenants of the district’s first apartment houses who were predominantly writers and theater people. In Part Three, we will learn more about Stuyvesant Square as it was during the critical periods for Alienist books, the 1880s and 1890s, and will focus our attention on some of the most prominent characters that contributed to the shaping of the district’s character during this period.

Stuyvesant Square’s fall from grace in the early 1880s

Even though the architectural charm of Stuyvesant Square had been established thirty years earlier with the building of handsome residential and religious buildings around the district’s attractively landscaped public park, by the early 1880s the district was becoming a shadow of its former self. Tenement populations were now encroaching on the neighborhood, and the district’s wealthier residents had begun to move further uptown in response. Although the park itself was still frequented by neighborhood children, the neglected park’s grass was no longer receiving any maintenance, its flowers had all but disappeared, and its two large fountains were filled with rubbish from the streets rather than water. One contemporary even recalled seeing “dead cats and empty tomato cans” piled in the fountain basins.

At the same time, the district’s iconic St. George’s Episcopal Church that had once drawn some of the largest congregation numbers of any religious institution in New York was also in the process of an equally sharp decline. Congregation numbers had started to fall while under the pastorship of the aging Rev. Dr. Tying in the early 1870s, and numbers had dropped still further following his death. During this period, St. George’s was funded by pew holders, of which there were few remaining due to the wealthy parishioners migrating uptown, and had accumulated $35,000 in floating debt. The financial situation had reached such a precarious point by the late 1870s that there were even reports that the Roman Catholic Church had been approached by members of the vestry to take the church over as a mission. Although members of St. George’s had tried on several occasions to build their numbers up through outreach to the poor, all attempts had been unsuccessful and were eventually abandoned.

When St. George’s attendance numbers reached their bleakest point in the early 1880s, the extremely conservative wardens and vestrymen of the church made a radical decision to approach the passionate reformer, the Rev. Dr. William S. Rainsford, to take over pastorship of the church. Although a surprising choice for an old-fashioned church, this decision would prove to not only turn around the fortune of the failing church but would help to shape the character of the district as a whole in the years to come.

| Continue reading →