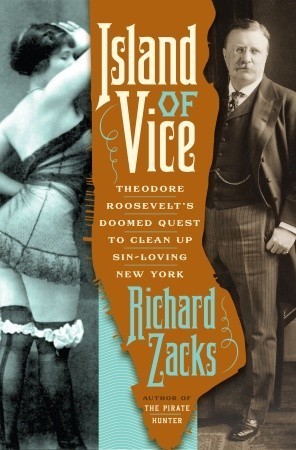

I had originally intended to spend the first few months of “book blogs” on 17th Street overviewing the works Caleb Carr has cited as inspirations for his novels. However, this month I would like to deviate from Carr’s inspirations to feature Island of Vice: Theodore Roosevelt’s Quest to Clean Up Sin-Loving New York, a nonfiction work by Richard Zacks that details Theodore Roosevelt’s tenure as police commissioner of New York from 1895 to early 1897. Island of Vice is the closest to a “companion book” for The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness I have read to date, offering a no-holds-barred, humorous, and fastidiously researched behind-the-scenes look at old New York, Theodore Roosevelt, and the New York City police department during the period in which the Alienist books were set.

What’s it about?

In February of 1892, Reverend Charles H. Parkhurst, president of the Society for the Prevention of Crime, shocked the 800 parishioners of Madison Square Presbyterian Church by delivering a sermon that accused the Tammany-dominated New York City police force, district attorney, and even the mayor of “licensing crime”. Claiming that disorderly houses, illegal casinos, and vendors of illegal liquor had their “immunity secured to [them] by a scale of police taxation”, he went on to tell his law-abiding parishioners that “your average police captain is not going to disturb a criminal if the criminal has means”. Tammany Hall officials responded to these accusations with outrage, and Parkhurst was called before a grand jury on charges of libel. He was found guilty, with the grand jury concluding that he had “no evidence” for his accusations; however, the reforming minister would not be deterred. In March of 1892, he hired a young private detective to “take him on the ultimate sin tour of New York City”. The sights he witnessed on their multi-night tour of saloons, dives, and disorderly houses resulted in Parkhurst providing the district attorney with 284 addresses of illegal gaming houses, disorderly houses, and after-hours saloons, and charges being laid against four brothel madams. This time, Parkhurst won. This series of events marked the beginning of a fight that would go on to last for the whole of the 1890s between New York reformers and the corrupt sectors of society; a fight that an up-and-coming Theodore Roosevelt would find himself headlining.

Island of Vice documents the period between 1892 and 1898 when New York’s reform movement tried in vain to “clean up” the corrupt American capital of finance, manufacturing, entertainment, and sin. This was a period when it would be difficult for any of New York’s two million residents to find themselves far from one of the city’s 8,000 saloons, hundreds of hotels, dives, and illegal casinos, or the hundreds of brothels that proffered an estimated 40,000 prostitutes to the men of the city. It was a hard-drinking city, with an estimated 460,000 eight gallon quarter-kegs of beer served each week, amounting to approximately “twenty pints per week for every man and woman over the age of sixteen in the city” — and that didn’t count the wine, whiskey, or other forms of liquor available at the time. When reform-minded Republican, William L. Strong, was elected mayor in 1895, he swore in a new four-man Police Board of Commissioners, of which young, energetic, and headstrong Theodore Roosevelt would go on to become President. The first order of business for the new reform police commissioners was to remove the corrupt old guard of the New York police force, starting at the top with Chief of Police Thomas Byrnes, and then to get to work enforcing laws the police force had been turning a blind eye to for years.

The City of New York, however, had other ideas.

My thoughts

Published in 2012, Island of Vice is Richard Zacks’ fifth book, and was met with well-deserved critical acclaim upon its publication. A native New Yorker, Zacks paints a vivid picture of the people and places that made up New York at the turn of the 20th century. Taking his readers on a colourful tour of old New York’s saloons, dives, and disorderly houses, Zacks describes what life as a New York cop was like in the 1890s, and introduces readers to both the well-to-do and seedier elements of society. Fastidiously researched, Zacks lets these characters speak for themselves through direct quotes from trial transcripts, letters, memoirs, interviews, and newspaper reports.

Throughout the book, we meet a number of historical figures familiar to any Alienist reader including (of course) Theodore Roosevelt himself, Thomas Byrnes, Anthony Comstock, Lincoln Steffens, and Jacob Riis, along with one or two other figures who may have served as inspiration to Caleb Carr when creating the original characters that appear in the Alienist books. Minnie G. Kelly, for example, was the first female police secretary who had been controversially hired by TR upon becoming police commissioner. Described as “young, small and comely, with raven black hair”, the bespectacled Kelly was hired by TR at $1,700 a year to replace two male secretaries who had cost the department a combined $2,900 a year. Although her hiring saved the department $1,200 a year, her presence in male-dominated Police Headquarters at 300 Mulberry Street was not well received. TR, on the other hand, reported himself happy with her performance during his time as commissioner, although he did concede that “she made her share of mistakes”, as described in the following humorous excerpt from the book, pg. 74:

He recalled dictating a letter about an overly aggressive officer. “I was obliged to restrain the virtuous ardor of Sergeant Murphy, who, in his efforts to bring about a state of quiet on the street, would frequently commit some assaults himself.” That’s what he said aloud; when Miss Kelly handed him the sheet, he read on the page: “I was obliged to restrain the virtuous ardor of Sergeant Murphy, who, in his efforts to bring about a state of quiet on the street, would frequently commit somersaults himself.” TR later wrote his sister that he couldn’t stop laughing long enough to reprimand her as he couldn’t banish the mental image of the rotund sergeant rolling down the street.

We also meet a number of other figures in Island of Vice who were not featured in The Alienist or The Angel of Darkness, but whose importance to the world of 1890s New York was unquestionable. One such figure who features prominently in Island of Vice is William “Big Bill” Devery, a Police Captain with strong ties to Tammany Hall who was taken to trial over allegations of corruption several times during the course of his career. “Big Bill” is presented as a nemesis of TR during his tenure on the Police Board, with the latter — working alongside his fellow police commissioners and Reverend Parkhurst — attempting to stop “Big Bill” from returning to the force in May of 1896 after he was acquitted of his charges of extorting a bribe during his most recent corruption trial. Unfortunately for TR and the rest of the Police Board, history did not go their way. “Big Bill” not only returned to the force, but only fourteen months after TR left the Police Board and New York itself, “Big Bill” was promoted to Chief of Police by the new Tammany-dominated Police Board; a fact that should give you a hint as to how long-lasting the 1890s attempts at reform lasted in the city.

As for the central character — TR himself — Zacks clearly attempted to paint a balanced portrait of the future President, hiding neither his faults nor his virtues. At the outset of Island of Vice, we meet a young Roosevelt who had spent the preceding six years holding a relatively obscure post on the Civil Service Commission in Washington D.C. He returned to New York with a desire to make a difference, and the energy to do so. He went on innumerable “midnight rambles” through the streets of the city with Jacob Riis and various other friends or colleages at his side to witness the city’s corruption and dissolution first-hand, earning him the newspaper nickname “Haroun el-Roosevelt” after the Thousand and One Nights’ caliph who explored Baghdad in disguise after dark. TR would describe these rambles as “great fun”, and they proved to be a highlight of both his tenure as police commissioner and of Zacks’ Island of Vice itself, with some of the amusing incidents that took place when he ventured out on the streets sounding more like vaudeville comedy acts than serious police work (pg. 268):

Roosevelt and his party alighted from the carriage just as the [saloon side door] cracked open and an arm suddenly emerged holding an oversized schooner of amber liquid. The policeman took the tankard, lifted it to his lips, and began drinking. Roosevelt, in a kind of racing tiptoe, sped across the street, reached the policeman, and tapped him roughly on the shoulder, sternly saying, “Officer, give me that beer.” The startled bluecoat, in mid-gulp, spritzed a geyser of foam and looked at the squat bespectacled man accosting him. Just then, a hand emerged from inside the bar, yanked the glass, and slammed the door shut. The patrolman took one look at Roosevelt, teeth and spectacles glinting in the moonlight, as one paper put it, and the man sprinted off without saying a word. [Police Commissioner] Andrews by now had reached the scene and the two commissioners raced after the bluecoat. “Stop running, you fool!” shouted Roosevelt. About fifty yards away, near the corner, they caught him. Roosevelt demanded his name. “Ginger ale,” he replied, gasping for air. “Ginger ale.”

TR threw himself enthusiastically into all aspects of his new post at Police Headquarters, and made some important strides forward during his two year tenure including overseeing fairer political elections. However, even though the President of the Police Board’s reforming zeal was initially well-received, when he set his sights on the city’s hard-drinking culture and began enforcing old excise laws that forbade liquor from being sold or consumed in saloons and other public watering holes between midnight on Saturday until early Monday morning, thereby banning alcohol on the one day per week working class men had off — in the middle of a long, hot summer, to boot — the tide of public opinion took a sharp turn. (It didn’t help that with a loophole allowing hotel restaurants to sell drinks to guests with meals, and exclusive private clubs not being mentioned in the law, affluent New Yorkers were effectively exempt.) Later, when cracks in the bipartisan Police Board began to show as a result of disagreements over hirings and promotions, things went from bad to worse for the crusading reformer. Within Island of Vice, we see a TR “with a reputation for absolute integrity” who publicly pursued his reform agenda in terms of black and white — good and evil — even while privately acknowledging to family members that some of the laws he was insisting be enforced were too harsh (pg. 122):

“I have now run up against an ugly snag, the Sunday Excise Law. It is altogether too strict but I have no honorable alternative save to enforce it and I am enforcing it to the furious rage of the saloon keepers and of many good people too; for which I am sorry.”

Even though Island of Vice’s focus was on TR’s tenure as police commissioner, Zacks devotes as much of the text to describing New York’s saloons, dives, disorderly houses, and court rooms, and I came away from the book feeling that the City of New York was, in fact, the most colourful character of all. Zacks clearly admires his city’s spirit of rebellion and survival despite the odds, as he demonstrates in his concluding statement in the epilogue of the book (pg. 365): “As in ancient Rome, the vitality of New York City sometimes seems to come more from the crooks than the do-gooders.” Although Island of Vice’s no-holds-barred approach results in an uneven read at times, with perhaps too much detail provided for a few seemingly irrelevant or repetitive episodes, it is ultimately a worthy addition to the library of any Caleb Carr reader interested in getting a behind-the-scenes glimpse of life in the city during the years in which The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness were set.