Welcome to the fourth and final part of the “Did Dr. Kreizler really live at 283 East 17th Street?” series. Over the course of this series, we’ve overviewed the origins of Stuyvesant Square from its earliest days through to the 1840s (Part One), read about the district’s most active period of development in the 1850s through to the early 1880s (Part Two), and learnt more about the enormous influence one reforming rector at St. George’s Church had on the district in the late 1880s and 1890s (Part Three). In this final blog of the series, we will be discussing why Caleb Carr might have selected the location as the home for his protagonist before briefly touching on how the district continued to develop in the early 20th century.

Why might Caleb Carr have chosen 283 East 17th Street as Dr. Kreizler’s residence?

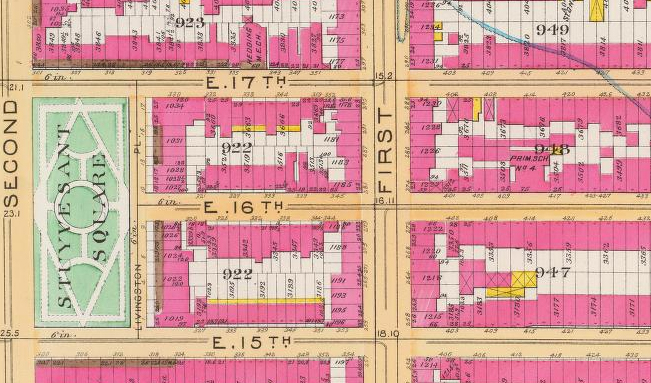

I feel it’s important to start this blog by stating the obvious: as I am not the author, I can only hypothesize as to why he may have chosen the fictional address of 283 East 17th Street as the home for his protagonist–and, yes, it is a fictional address. As can be seen in the 1891 maps of the district to the right and below, the section of 17th Street overlooking the park that was described as the location for Doctor’s home is bisected by Second Avenue. On the western side of Second Avenue, lot numbers ended at No. 251 (originally the Hamilton Fish mansion, later turned New York Lying-In Hospital; see below), while on the eastern side of Second Avenue, lot numbers started again at No. 301. Nevertheless, by examining the district’s composition in the 1890s, as well as overviewing the proximity of the neighborhood to other locations of importance in the Alienist books, we can start to theorize about why Caleb Carr might have selected the location. In addition, as Mr. Carr had his own connections to the district in his youth, it seems likely that this may have also played a role in his choice of Stuyvesant Square as the Doctor’s home.

| Continue reading →