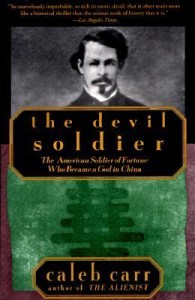

Included below is a summary of Caleb Carr’s second non-fiction work, The Devil Soldier: The American Soldier of Fortune Who Became a God in China, which was published by Random House in 1991. Selected critical reception has also been included. For summaries and selected critical reception of Caleb Carr’s other fiction and non-fiction works, please use the menu.

The Devil Soldier Summary

17th Street’s Blurb

Within The Devil Soldier, Caleb Carr presents the fascinating story of American soldier of fortune, Frederick Townsend Ward, who commanded an army for the imperial Chinese government during an incredibly savage civil war known as the Taiping rebellion. Ward’s tale is both thrilling and inspiring; the odds that he faced were astounding, and his achievements were remarkable. It would be difficult not to like the portrait of Ward that Carr paints throughout this action-packed biography, and the reader is bound to develop some degree of affection for “the small man in the blue coat.”

Due to the lack of primary research material relating to Ward’s life, The Devil Soldier is as much a work examining the social, political, and military history of China in the mid-19th century as it is a biography of the man himself. Although this work may be best appreciated by those who have some prior knowledge of military history, even readers without any useful background in this field of study will find this well-written and meticulously researched biography an interesting and enjoyable read.

The Devil Soldier Critical Reception

In this book Caleb Carr, a novelist and a contributing editor of Military History Quarterly, argues that Ward was more than just the foreign “devil soldier” he was dubbed by the Taipings, and more than just an opportunistic mercenary exploited by a brutally corrupt dynasty in the bloodiest civil war in history … Despite the handicap of hardly any firsthand evidence (in a long tradition of unhelpful relatives, Ward’s sister-in-law burned all his papers), Mr. Carr in “The Devil Soldier” builds up a picture of a bright-eyed, courageous loner, the ultimate freelance, “answering to a set of values of his own devising” — values that, Mr. Carr suggests, were essentially right-minded — and, along the way, living “one of the great adventures in the history of Chinese-Western relations.” … By marshaling his scholarship well and setting it out as an adventure story, Mr. Carr gives a good picture of the buccaneering milieu of the time, and makes a plausible case for the devil soldier being on the side of the angels.

Imagine an American version of Lawrence of Arabia at large in 19th-Century China, add the devil-may-care exploits of Indiana Jones and the high moral purpose of Robin Hood, and you’ll have a rough idea of what the adventurer Frederick Townsend Ward was really like. His story, recounted by Caleb Carr in “The Devil Soldier” with authority and high spirits, is so marvelously improbable, so rich in exotic detail, that it often reads more like an historical thriller than the serious work of history that it is.

If ever a book of history were made for the movies, Caleb Carr’s “The Devil Soldier” is it. Frederick Townsend Ward, who led an imperial Chinese army against the Taiping rebels in the mid-19th Century, was a larger-than-life figure. Yet so little is known about Ward that no filmmaker need worry about being accused of taking liberties … Making a full-length biography out of the fragments of Ward’s life is not easy. Carr’s strategy is to spend considerable time speculating about the missing pieces and to describe at length the foreign and domestic politics swirling around Ward. “The Devil Soldier” is as much a history of the Chinese civil war as a biography of one of its leading generals.

Publisher’s Weekly:

With Yankee self-reliance, penniless soldier-of-fortune Frederick Townsend Ward (1831-1862) from Salem, Mass., made himself indispensable to China’s Manchu dynasty in its bloody crushing of the Taiping rebellion of 1859. Assembling and commanding a highly disciplined army of native Chinese soldiers in Shanghai, Ward was officially made a mandarin by China’s rulers. “In every sense a free-lance'”–a questioner of authority, military doctrine and even of national loyalty–he became a Chinese citizen and in 1862 married Yang Chang-mei, daughter of his most loyal backer. He died in battle the same year; his wife survived him by just one year, apparently dying of “extreme grief.” In this sympathetic, solid biography, Carr focuses on political and diplomatic history, portraying the adaptable mercenary as a harbinger of later efforts to open China to Western assistance.