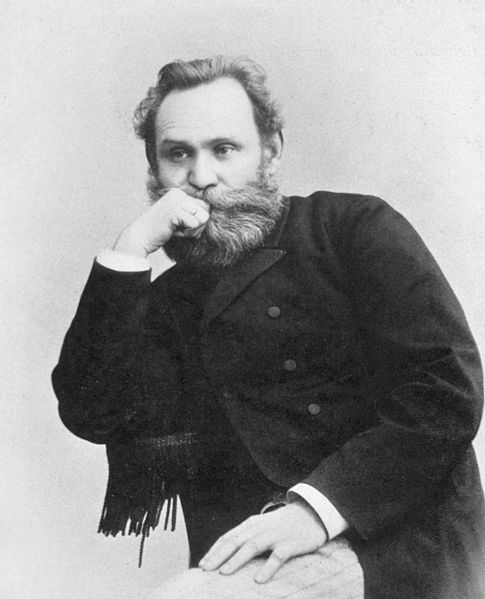

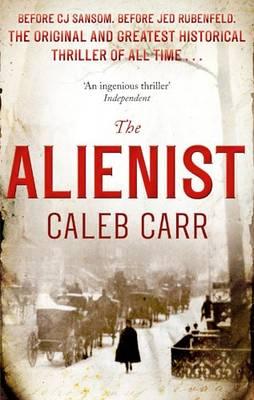

Within The Angel of Darkness we meet one of Stevie Taggert’s friends, the endearing orphan and petty criminal Hickie the Hun, who allows Stevie to borrow one of his many animals to assist the team during their investigation. Hickie had originally trained the animal, a ferret named Mike, to locate specific scents in order help him commit his robberies. When Hickie drops Mike off to Dr. Kreizler’s house, the Doctor is impressed by Hickie’s “homegrown methods of animal training” and jokingly suggests that the famous Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov, would benefit from talking to Hickie about his training methods. In Part One of the Hickie the Hun’s Homespun Behaviorism series, we examined how Pavlov’s research into animal learning in the 1890s related to Hickie’s training methods, and established that although Pavlov would indeed have been fascinated to learn about Hickie’s methods just as Dr. Kreizler suggested, the learning Hickie was employing was ultimately of a different form to what Pavlov investigated with his conditioning research. As a result, the second half of this two-part blog series will feature another researcher, this time a young American psychologist, who would go on to become famous just one year following the events of The Angel of Darkness when he published the first formal research into the same type of learning Hickie had been employing. However, before we go into more detail, let’s take another look back at Stevie’s description of Hickie’s training methodology:

Within The Angel of Darkness we meet one of Stevie Taggert’s friends, the endearing orphan and petty criminal Hickie the Hun, who allows Stevie to borrow one of his many animals to assist the team during their investigation. Hickie had originally trained the animal, a ferret named Mike, to locate specific scents in order help him commit his robberies. When Hickie drops Mike off to Dr. Kreizler’s house, the Doctor is impressed by Hickie’s “homegrown methods of animal training” and jokingly suggests that the famous Russian physiologist, Ivan Pavlov, would benefit from talking to Hickie about his training methods. In Part One of the Hickie the Hun’s Homespun Behaviorism series, we examined how Pavlov’s research into animal learning in the 1890s related to Hickie’s training methods, and established that although Pavlov would indeed have been fascinated to learn about Hickie’s methods just as Dr. Kreizler suggested, the learning Hickie was employing was ultimately of a different form to what Pavlov investigated with his conditioning research. As a result, the second half of this two-part blog series will feature another researcher, this time a young American psychologist, who would go on to become famous just one year following the events of The Angel of Darkness when he published the first formal research into the same type of learning Hickie had been employing. However, before we go into more detail, let’s take another look back at Stevie’s description of Hickie’s training methodology:

The Angel of Darkness, 210:

Would Mike be able to detect if the person was in fact in the house, and find the right room? Indeed he would, Hickie said; in fact, it would be a breeze, compared to some of the jobs Mike’d handled in the past. Then I asked about the training, and was surprised to learn how simple it would be: all I’d need would be a piece of clothing from the person I was looking for, the more intimate the better, as it would be that much more steeped in the person’s scent. Mike was already so well trained that when he began to connect a particular object or smell with his feeding, he quickly got the idea that he was supposed to find something that looked or smelled the same; only a couple of days would be needed to get him ready.

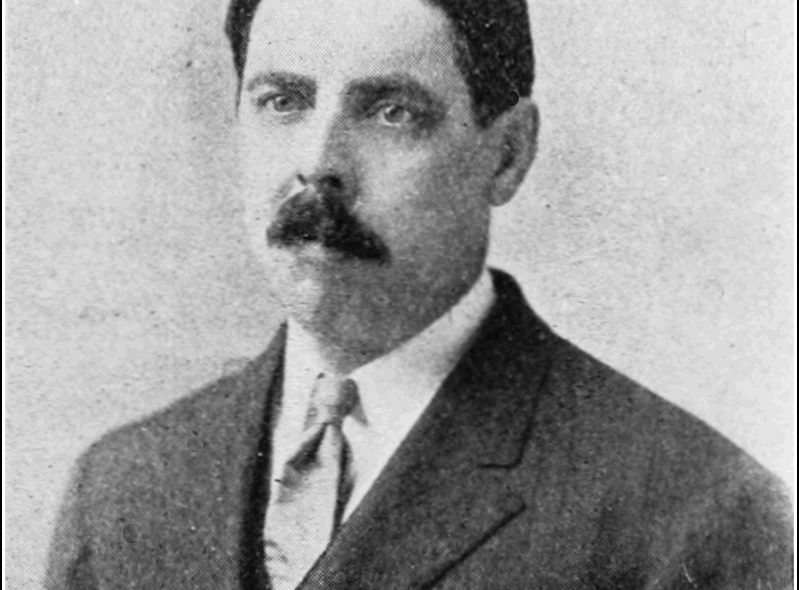

As we discussed in Part One, we can see from this extract that Hickie was using meat as a means of rewarding Mike for performing a desired behaviour, a technique that would come to be known as positive reinforcement from the 1930s onwards when another renowned American psychologist, Burrhus F. Skinner, established operant conditioning as the other half of ‘behaviourism’, a field of psychology John B. Watson had popularised in the 1910s on the basis of Pavlov’s classical (or Pavlovian) conditioning. However, three decades prior to Skinner, another American psychologist, Edward Lee Thorndike, was conducting the research that would form the foundation of Skinner’s work. Thanks to Thorndike’s innovative methods, his research would take the world of psychology by storm when it was first published in 1898, and within the year he would have publications in the prestigious generalist journal Science and the equally prestigious specialist journal Psychological Review, and would be invited to present his work at both the New York Academy of Sciences and the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association. Little did Hickie the Hun know that he had anticipated what would become one of the most important and revolutionary ideas in animal and human learning — no wonder Dr. Kreizler was impressed! | Continue reading →