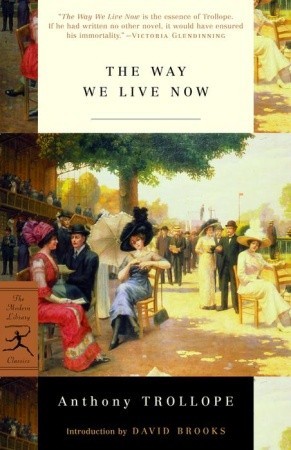

In order to provide a short break from posting news on the blog, I’ve decided to feature a book blog this month about a novel I recently read for the first time: The Way We Live Now by Anthony Trollope. Although I hadn’t intended to discuss this hefty classic (it ranges in page length, depending on edition, from 800 to over 1000 pages) on 17th Street, by the time I reached the three-quarter mark in my reading, I came to feel that I would be doing this masterpiece of literature a disservice if I did not feature it here. Aside from sharing several themes with the Alienist novels, it also introduces a cast of some of the strongest female characters in all of literature. As a result, it has quickly become one of my favourites; and who knows — if you give it a chance, it might become one of yours, too.

What’s it about?

Written in 1875 after Anthony Trollope returned to England following a two-year trip to Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, The Way We Live Now is a powerful satire of English politics, speculative finance, and society. Originally intended to be a novel about the Carbury family before it morphed into something far grander, The Way We Live Now opens by introducing the reader to the enterprising Lady Carbury who is single-handedly attempting to support her two adult children, Sir Felix and Hetta, through the publication and self-promotion of her first book, a facetiously titled work called Criminal Queens. Throughout the pages that follow, the lives of Lady Carbury and her children, along with those they are connected with, become intertwined with the towering figure of the novel, Augustus Melmotte: financier, aspiring politician, — and swindler.

As we watch as Melmotte’s rise and fall, we gain a new perspective on themes that range from corruption to the role of women in society and the secret world of the family behind closed doors. While it may have been written over one hundred and forty years ago, its masterly presentation of timeless themes and characters makes The Way We Live Now a novel of our own age as much as it is a novel of English society in the early 1870s.

My thoughts

I went into The Way We Live Now with high expectations; however, it would seem that my expectations were not high enough! I’ve read many novels history holds up as “great,” but I can count on one hand the novels that I personally consider to be “masterpieces.” This, I am pleased to say, is one of them. Having previously seen the excellent 2001 miniseries starring David Suchet as Augustus Melmotte, I was already aware of the plot and knew that I would appreciate most of the themes Trollope explores. Although the first hundred pages is somewhat slow while the large cast of characters is introduced (we follow the stories of over ten main characters, in addition to numerous lesser characters), by the half-way point it became so gripping — even though I already knew the plot! — that it would be best described as a “page turner.”

More surprising than this, I hadn’t been expecting to feel quite so emotionally connected to several of the main characters. Trollope deals with difficult subject matter, including emotional and physical abuse, and there were times when I felt so drained that I needed to give myself a break before continuing. Related to this, it’s rare that I come out of a book naming one of the females as my favourite character. It is rarer still that I find a “strong” female character so realistically formed that I am willing to consider her one of my favourite female characters of all time. So you can imagine my delight when I found just such a character in The Way We Live Now.

In order to discuss these subjects in more detail, unfortunately I need to verge into spoiler territory. As a result, this will be a somewhat unusual book blog as I will be ending the spoiler-free section of my thoughts here, and then continuing my discussion (spoilers included) under the link, which also includes a discussion of the themes I feel the novel shares with the Alienist books. If you have not read the book but are interested enough at this point to give it a try, I encourage you to do so and come back to read the rest of my thoughts later to see if you agree with me. However, if you have already read the novel, or don’t care about being spoiled, then by all means read on!

The first of the themes that I feel are shared with the Alienist books — namely, the role of women in society and the secret world of the family behind closed doors (this includes abuse) — are connected to my strong feelings toward the female characters in the novel. Although I’ve previously stated that I have one particular favourite, it is important to mention that the entire cast of female characters in the novel is one of the strongest I’ve found in a single volume. None are one- or two-dimensional. All have strengths along with weaknesses and failings. All have rich inner lives. Many are strong enough to want to build a life for themselves independently of the men who surround them. For a male novelist writing in 1875 to have produced such a cast is astonishing.

So, let us start with the woman who opens the novel, Lady Carbury. The title of the book she is in the process of self-promoting is Criminal Queens, which amusingly enough is an apt description of its writer. However, in spite of her faults, Trollope takes great pains to encourage his readers to empathise with Lady Carbury. She might have no scruples in how she becomes successful, but she is determined to single-handedly provide for her children without resorting to finding another husband (even if at least one of those children, Sir Felix, doesn’t deserve it), and early in the novel we find out why: Lady Carbury’s former husband was abusive. She therefore values her freedom above all things. As Trollope explains,

Chapter XXXI: Mr. Broune Has Made Up His Mind

And then her liberty! Even though Felix should bring her to utter ruin, nevertheless she would be and might remain a free woman. Should the worse come to the worst she thought that she could endure a Bohemian life in which, should all her means have been taken from her, she could live on what she earned. Though Felix was a tyrant after a kind, he was not a tyrant who could bid her to do this or that. A repetition of marriage vows did not in itself recommend itself to her.

Thus, when she receives an unexpected offer of marriage from her friend and ally, Mr. Broune, it does not take long for her to resolve on turning him down, even though marriage would save her financially. In a moving letter to Mr. Broune she writes,

Chapter XXXVI: Mr. Broune’s Perils

I cannot but be proud that such a one as you should have asked me to be his wife. But, my friend, life is subject to wounds which are incurable, and my life has been so wounded. I have not strength left me to make my heart whole enough to be worthy of your acceptance. I have been so cut and scotched and lopped by the sufferings which I have endured that I am best alone … I should bring showers instead of sunshine, melancholy in lieu of mirth.

I will, however, be bold enough to assure you that could I bring myself to be the wife of any man I would now become your wife. But I shall never marry again.

Even so, the friendship continues to grow between Mr. Broune and Lady Carbury, and eventually it comes to pass that she sees their relationship in a different light. Although Lady Carbury is not my favourite of people — I doubt very much that I would get on with her in real life! — the gradual evolution of this relationship is one of my favourites in the novel, and I am so pleased that it ended the way it did. However, Lady Carbury earned my respect, just as she earned Mr. Broune’s respect, when she put her financial interests second to her independence. I fear there are few, especially in those days, who would have had the fortitude to do the same. This can be seen most clearly in the character of Georgiana Longstaffe, who at nearly thirty years old is desperate to find a husband so that she can leave the family home. Although Georgiana is one of the least sympathetic females in the novel, Trollope still encourages us to see things from her perspective and to realise how hard it could be for a woman who desired independence or freedom in those days.

Chapter LXXVIII: Miss Longstaffe Again at Caversham

“I’ve done with you all,” said Georgey rushing out of the room. “I’ll have nothing more to do with any one of you.”

But it is very difficult for a young lady to have done with her family! A young man may go anywhere, and may be lost at sea; or come and claim his property after twenty years. A young man may demand an allowance, and has almost a right to live alone. The young male bird is supposed to fly away from the paternal nest. But the daughter of a house is compelled to adhere to her father till she shall get a husband.

Two other female characters, Hetta Carbury and Ruby Ruggles, also face similar problems when their families pressure them to marry men they do not desire. While Hetta’s mother merely tells her daughter off for her refusal to marry her wealthy cousin (do not suppose my respect for Lady Carbury’s decision not to marry again extends to, or excuses, her hypocrisy on this point), Ruby’s grandfather becomes physically violent when his granddaughter turns down the suitor of his choice. Ruby, holding unrealistic hopes for marriage to a man of a very different sort, resolves to take refuge in the home of a distant relative and runs away. Again, the limited choices females of his period had are driven home strongly in the characters of both these women; but both show fortitude in fighting for their rights, whether it be through passive (Hetta) or active (Ruby) means.

And with this, we move on to one of the most remarkable characters in the novel who shares a great deal of similarity — at least in one respect — with Sara Howard. Mrs Hurtle, considered by Trollope to be one of the most interesting characters in the novel, is an American divorcee with a dark past that includes, among other things, shooting a man who had mistreated her. This causes no end of worry to one of the men in the novel, Paul Montague, who engaged himself to the attractive divorcee during his travels in the United States; determined after consultation with his mentor back in England that the marriage would be inadvisable; and then found that Mrs Hurtle had followed him to London. Although Mrs Hurtle does not revert to such methods to avenge herself in Paul’s case, she does force the reader to question the double standards that apply to women when it comes to fighting for one’s own skin. This is particularly driven home when she shows Paul a letter, written in passionate rage, in which she threatened him with a horsewhip for his poor treatment of her.

Chapter LI: Which Shall It Be?

“I do not think that under any provocation a woman should use a horsewhip.”

“It is certainly more comfortable for gentlemen, — who amuse themselves, — that women should have that opinion. But, upon my word, I don’t know what to say about that. As long as there are men to fight for women, it may be well to leave the fighting to the men. But when a woman has no one to help her, is she to bear everything without turning upon those who ill-use her? Shall a woman be flayed alive because it is unfeminine in her to fight for her own skin? What is the good of being — feminine, as you call it? Have you asked yourself that? That men may be attracted I should say. But if a woman finds that men only take advantage of her assumed weakness, shall she not throw it off? If she be treated as prey, shall she not fight as a beast of prey? Oh no; — it is so unfeminine!”

However, Mrs Hurtle is far from a one-dimensional character. Although many in the story do tend to see her purely as a “wild cat,” she ultimately wins several friends who see her for the complex — and indeed, kind — character that she really is. And this, finally, brings us to my favourite of the characters. In my three-part series discussing The Alienist’s themes, I mentioned my admiration for characters whose strength arises from adversity. While this can certainly be seen in characters such as Lady Carbury and Mrs Hurtle, in my view nobody better embodies this in The Way We Live Now than Marie Melmotte, the daughter of Augustus Melmotte.

Consistently underestimated by her father, Marie Melmotte ultimately proves to be his downfall. Indeed, the men who become entangled with Marie throughout the various marriage plots within the novel typically see her more clearly than her own parent does. Lord Niddlerdale, for example, who becomes engaged to Marie through a deal struck between his father and Melmotte, explicitly tells the latter, “To tell you the truth, sir, I think Miss Melmotte has got a will of her own stronger than you give her credit for.” Even Sir Felix, more interested in himself than anybody else, came to feel some admiration for Marie when she chose to engage herself to him despite her father’s violent opposition to the match, and then proposed to run away with him using money her father had hidden in a bank account under her name.

Chapter XXIX: Miss Melmotte’s Courage

Sir Felix as he read this could not but think that he had become engaged to a very enterprising young lady. It was evident that she did not care to what extent she braved her father on behalf of her lover, and now she coolly proposed to rob him … He had looked upon the lady of his choice as a poor weak thing, without any special character of her own, who was made worthy of consideration only by the fact that she was a rich man’s daughter; but now she began to loom before his eyes as something bigger than that. She had had a will of her own when the mother had none. She had not been afraid of her brutal father when he, Sir Felix, had trembled before him.

Nonetheless, there is real tragedy in Marie’s character. Sir Felix’s description of the father as “brutal” in the preceding quote is accurate. Later in the novel Marie reveals to Felix’s sister, Hetta, that her father beats her. However, she goes on to say that she “never will yield a bit for that. When he boxes and thumps me I always turn and gnash my teeth at him.” Unfortunately, despite Marie’s courage, her father’s abusive behaviour and emotional neglect has left her vulnerable to the unscrupulous behaviour of a man like Sir Felix who is willing to say anything in order to lay his hands on her fortune. She has never been loved, and longs for someone to show her genuine affection. In many ways, Marie’s falling for Sir Felix is reminiscent of the relationship between Beecham and his victims in The Alienist. As John explains to Sara, the boys Beecham targets are only suspicious and skeptical “on the outside … inside, they’re praying for a real friend.” Similarly, Marie asks Hetta: “Can you wonder that I want to have a friend?”

Even so, the novel takes its most interesting turn, both in terms of plot and character development for Marie, when Melmotte’s underhanded financial dealings bring him close to destruction. It is only when he decides that he needs to claim the fortune he has hidden in Marie’s name to save himself that he discovers Lord Nidderdale had better understood his daughter’s intelligence and strength of character than he did.

Chapter LXXIII: Marie’s Fortune

And indeed, there was another complication which had arisen within the last few days and which had startled Mr. Melmotte very much indeed. On a certain morning he had sent for Marie to the study and had told her that he should require her signature in reference to a deed … Then Marie astounded him, not merely by showing him that she understood a great deal more of the transaction than he had thought, — but also by a positive refusal to sign anything at all … He did not know whether to approach her with threats, with entreaties, or with blows. Before the interview was over he had tried all three. He had told her that he could and would put her in prison for conduct so fraudulent. He besought her not to ruin her parent by such monstrous perversity. And at last he took her by both arms and shook her violently. But Marie was quite firm. He might cut her to pieces; but she would sign nothing.

Much as these scenes, along with other scenes like it, were distressing to read, my admiration for Marie’s fighting spirit and courage only grew over the course of the novel. Her character shows such significant development by the end of the novel that, after she has been betrayed by more than just her father, she comes to the conclusion that “go where she might, she would now be her own mistress.” Even some of her father’s associates return to her service after his fall when it seems that she will end up becoming a business woman in her own right. However, as one such individual observes, she has a stronger character than her father and will not make the same mistakes as him. She also “had opinions of women’s rights, — especially in regard to money.”

Nonetheless, for all Augustus Melmotte’s terrible behaviour toward his daughter and others, Trollope takes pains to help the reader understand that the financier’s character has its origins in his early life as well. Even though Melmotte forges and robs over the course of the novel, Trollope explains to the reader: “That, indeed, was nothing, for he had been cheating and forging and stealing all his life.” And what was that life? We eventually discover that he had been “brought into the world in a gutter, without father or mother, with no good thing ever done for him.” We therefore learn that these are things Melmotte learned to do in order to survive; yet another theme that the novel shares with The Alienist. This can be observed in the other characters of the novel as well, ranging from the women already mentioned through to the unscrupulous Sir Felix and even the entertaining (if dreadfully lazy and ignorant) Dolly Longstaffe.

The Way We Live Now also explores one other theme that was touched on in The Alienist: anti-semitism. Madame Melmotte, a suspected Jewess, is thought of poorly by those in society throughout the novel. Later we also meet Ezekiel Breghert, a Jewish banker, who becomes engaged to Georgiana Longstaffe. Mr. Breghert is initially described through the eyes of the Longstaffes in a less than flattering light, and when Georgiana’s mother finds out about the engagement she feels that, “such an occurrence in the family would … be to her as though the end of all things had come.” Nonetheless, his portrayal becomes more sympathetic as the novel progresses. Trollope shows him to be a good man — far better, in fact, than the Longstaffes.

There are, of course, numerous other aspects of the novel that I could discuss here, but these are the aspects I feel are most pertinent for readers of the Alienist books. If part of the reason you love The Alienist is for its social commentary and strong characters, then perhaps you should consider picking up The Way We Live Now if you haven’t done so already. If you enjoy it half as much as me, it will be worth the effort.

Thank you. I enjoyed your commentary a great deal.