Late last month, we began an examination of Sara Howard’s historical context in an effort to understand the kind of upbringing, education, and career choices a young woman born in a similar decade and socioeconomic group to Sara would have had available to her in the late 19th century. I termed this woman a “hypothetical” Sara, and today’s post will build upon on last month’s to discuss the pre-college and college educational opportunities our hypothetical Sara would have had during the 1870s and 1880s in New York.

The Pre-College Years

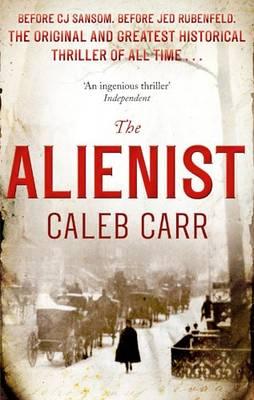

The Alienist, 90-1:

“… My father was an expert marksman. My mother, however, was an invalid, and I had no siblings. I therefore became my father’s hunting and trap-shooting partner.” All of which was perfectly true. Stephen Hamilton Howard had lived the life of a true country squire on his estate near Rhinebeck, and had trained his only child to ride, shoot, gamble, and drink with any Hudson Valley gentleman – which meant that Sara could do all those things well, and in volume.

As described in Part One, our hypothetical Sara was an only child born to an upper-class New York family in the mid-to-late-1860s. Given her father’s ownership of a Hudson Valley estate as well as a city home on Gramercy Park, it seems reasonable to assume that he would have shared some of the values common among old New York gentility such as the importance of “good looks, health, grace, and cleverness” in women. However, as the quote above describes, this particular father seemed to be determined to provide his only daughter with the same advantages he would have offered a son. Although this would have resulted in our hypothetical Sara receiving an education superior to that received by many girls during the same period who were frequently educated in “practical” subjects at home for most of their youth, statistically Sara’s was not an unusual upbringing for girls raised by educated parents in middle- and upper-class families in the Northeast—provided, of course, that their daughters were only children or had few brothers. Even though most of these parents still ultimately desired their daughter enter the respectable sphere of domesticity once she reached her early-to-mid-20s, a good education during her formative years reflected the family’s belief in the value of self-improvement and personal advancement (also see Part One).

Early Education

In her earliest years, our hypothetical Sara would have learned rudimentary reading and writing at home from her caregivers. However, given that Sara’s father desired her to receive the same educational opportunities as a son, she would have been expected to begin some kind of formal education—most likely at a private graded school—from approximately the age of seven. As schooling was unstandardised in the 19th century, the education she received at school would have been wholly dependent on the competence of her teachers, who, given their student’s young age and the fact that she lived in an urban area, would most likely have been female. Teaching had been a socially acceptable occupation for females throughout the 19th century, but women found their greatest opportunities for employment in urban schools where they were hired to teach the lower grades while male teachers held higher grade positions and positions of authority (principals and superintendents).1

In her earliest years, our hypothetical Sara would have learned rudimentary reading and writing at home from her caregivers. However, given that Sara’s father desired her to receive the same educational opportunities as a son, she would have been expected to begin some kind of formal education—most likely at a private graded school—from approximately the age of seven. As schooling was unstandardised in the 19th century, the education she received at school would have been wholly dependent on the competence of her teachers, who, given their student’s young age and the fact that she lived in an urban area, would most likely have been female. Teaching had been a socially acceptable occupation for females throughout the 19th century, but women found their greatest opportunities for employment in urban schools where they were hired to teach the lower grades while male teachers held higher grade positions and positions of authority (principals and superintendents).1

Nevertheless, the training female teachers received in the early decades of the 19th century was generally poor. The majority of female teachers in the Northeast were young (aged between 16 and 25), had only received a common school education, and regarded teaching as a temporary career while awaiting marriage (the average tenure was 2.1 years). Although training for Northeastern women improved significantly with the opening of academies such as the Troy Female Seminary and Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, a large number of graduates from these more advanced teaching academies chose to take their skills to the West or South in lieu of missionary work following the Civil War (unmarried women were denied missionary scholarships) rather than remaining in the Northeast. Despite this, women in the Northeast continued to dominate the profession, largely for financial reasons: they were only paid 40% of the salary of male teachers, making their hire attractive to school principals and superintendents, and it also offered an opportunity for girls from lower income families, particularly those from smaller towns, to help supplement their family’s income prior to marriage.

Returning to our hypothetical Sara’s early schooling, we can get some idea of the kind of education she may have received by reviewing the recollections of Margaret Floy Washburn, a notable scientist who was also an only child born to a New York family during a similar decade to Sara. Although Margaret’s family belonged to a slightly lower social class than Sara’s, they particularly valued education and gave their daughter every advantage available to girls at the time. Of her own first school located near her home in upper Manhattan, Margaret recalled:

The first school was a private one kept by the Misses Smuller, the three accomplished daughters of a retired Presbyterian minister who lived in the next house. It would be hard to find better teaching anywhere at the present time. In my year and a half there I gained, besides the rudiments of arithmetic, a foundation in French and German that saved me several years in later life, and the ability to read music and play all the major and minor scales from memory…

In addition to arithmetic, modern languages, and music, our hypothetical Sara’s early schooling would have included American history and elementary science, as well as further developing her reading, writing, and vocabulary skills. At around the age of twelve or thirteen, she would then have been required to sit the preliminary Regents’ examinations, a requirement for all eighth grade pupils in New York State to proceed into high school. These public examinations involved papers being sent from Albany to all participating schools. Those students who passed were sent a certificate that entitled its holder “to admission into the academic class in any academy subject to the visitation of the Regents, without further examination.”

High School

The next step for our hypothetical Sara would have been attending high school. A coeducational academy would probably have been the most advantageous choice for an ambitious young girl who desired to go onto college as it would provide her with her best chance of avoiding having to take additional college preparatory work after graduation. However, even at coeducational academies that allowed girls to participate in the same courses that prepared boys for colleges such as Harvard, girls ran into problems in achieving equal educational opportunities, as one group of young women who attended a coeducational high school in the late 1870s found:

The boys in the High School were so ugly to us girls who were going to college that they made life very disagreeable, and when no boys took Greek he [sic] would not start a class for the girls and we found ourselves one year backward in Greek and had to hire Mrs. Graham to tutor us all the summer vacation before Smith [College] opened.

Other schools simply didn’t allow girls to take college preparatory courses that were deemed unsuitable or unnecessary for their sex, and offered replacements for female students such as needlework instead of arithmetic or comportment instead of Latin. Even for those girls who didn’t face problems of exclusion from college preparatory courses, the standard of instruction varied widely. As an example, let us return to Margaret Floy Washburn’s recollections of her education, this time regarding her experiences at Ulster Academy in Kingston, New York:

Other schools simply didn’t allow girls to take college preparatory courses that were deemed unsuitable or unnecessary for their sex, and offered replacements for female students such as needlework instead of arithmetic or comportment instead of Latin. Even for those girls who didn’t face problems of exclusion from college preparatory courses, the standard of instruction varied widely. As an example, let us return to Margaret Floy Washburn’s recollections of her education, this time regarding her experiences at Ulster Academy in Kingston, New York:

The curriculum at Ulster Academy covered three years and would deeply distress a modern authority. It consisted of short-term courses in a large variety of subjects, each of which supplied a certain number of “Regents’ credits.” This method gave very poor results in the sciences, and my entire class failed twice to pass the Regents’ examination in chemistry, having had no laboratory work … However, the course in “political economy” firmly fixed in one’s mind the rudiment’s of the theory of supply and demand, and that in “civil government” equipped one with some lasting idea of the structure of state, county, township, and city. We had to learn the Constitution of the United States thoroughly … Passing Regents’ examinations in Latin had somewhat the nature of a sporting event. Having read four books of Virgil, we tried the examination on all six, reading at sight the passages from the last two. Several of us got over this hurdle, and the Aeneid knew us no more.

As Margaret’s recollections indicate, pupils attending any one of up to one hundred participating high schools across New York State were required to sit Regents’ examinations from 1878 onwards. The first examinations covered only five subjects—algebra, American history, elementary Latin, natural philosophy, and physical geography—but from 1879 onwards, they covered an extremely wide curriculum (42 subjects in all) that included the preceding subjects along with other subjects such as rhetoric and English composition, English literature, science of government, general history, physiology and hygiene, zoology, astronomy, botany, geology, Latin prose composition, Greek grammar, French translations, German grammar, bookkeeping, and drawing.

After several years of high school and passing her Regents’ examinations, our hypothetical Sara would have been ready for the next phase in her life. Although many young women delayed college in order to work as teachers for a few years to help finance further education (tuition and board at a woman’s college usually cost a minimum of $300-$350 per year during a time when an average teacher’s salary was $250 per year), it seems unlikely our hypothetical Sara would have needed to resort to such measures. Instead, it is more feasible that Sara’s family may have decided to take her abroad to Europe for a summer before entering college. Travel abroad at the completion of a young person’s education was extremely common among families with means throughout the 19th century for the cultural enrichment it provided. However, regardless of what Sara did immediately following graduation, we are told within The Alienist that she went on to complete higher education, so shortly after graduating high school she would have needed to apply to her college of choice.2

The College Years

In the mid-to-late-19th century, women had limited options for higher education. A small number of Midwestern colleges and universities had started admitting women as early as the 1830s, however none of these institutions were supportive of women transcending their socially accepted sphere of domesticity beyond the profession of teaching. Oberlin, the first college to open its doors to women, restricted female pupils to a “subordinate, domestic role within the college”. Stanford, one of the first universities to incorporate female students from the time of its opening in 1891, “maintained as its real mission the production of educated wives and mothers” rather than preparing women for careers outside the home, and fostered an environment where women felt “invisible” and “ignored”. Many Midwestern institutions, despite claims of coeducation, continued to keep women segregated from male students and directed female pupils to the limited number of socially acceptable women’s professions.

In the mid-to-late-19th century, women had limited options for higher education. A small number of Midwestern colleges and universities had started admitting women as early as the 1830s, however none of these institutions were supportive of women transcending their socially accepted sphere of domesticity beyond the profession of teaching. Oberlin, the first college to open its doors to women, restricted female pupils to a “subordinate, domestic role within the college”. Stanford, one of the first universities to incorporate female students from the time of its opening in 1891, “maintained as its real mission the production of educated wives and mothers” rather than preparing women for careers outside the home, and fostered an environment where women felt “invisible” and “ignored”. Many Midwestern institutions, despite claims of coeducation, continued to keep women segregated from male students and directed female pupils to the limited number of socially acceptable women’s professions.

In the Northeast, although female seminaries such as Troy and Mount Holyoke had improved women’s education dramatically, they were unable to confer degrees for most of the 19th century (Mount Holyoke’s first Bachelor degrees were awarded in 1889) and their ultimate aim was to prepare women for a profession in teaching. The most radical change in women’s higher education came with the opening of Vassar College in 1865, which aimed to provide women with educational opportunities equal to those available at prestigious male universities such as Harvard and Yale. The opening of Vassar represented the first chance at true educational equality for women, and ambitious girls from the middle- and upper-classes were keen to attend. One bright young woman who went on to have an illustrious career in the sciences, Christine Ladd-Franklin, had been one of Vassar’s first attendees in the late 1860s. Although her father had allowed her to spend two years at a coeducational academy studying the same college preparatory courses as boys, he was less open-minded about his daughter attending the newly opened women’s college. When he finally did concede, the news was met with rapturous joy in Christine’s diary: “Vassar! Land of my longing! Mine at last.” However, the strong disapproval she had felt from her family prompted fears as well: “Does it really seem so beautiful as I thought it would? Is it really for the best? I confess I have misgivings—everyone is so opposed to it.”

Even with opposition from a skeptical public (one skeptic, a year after the college opened, mocked, “You can lead a girl to Vassar, but you can’t make her think.”), the Vassar experiment worked and within a decade another two women’s colleges opened in the Northeast: Smith College and Wellesley College. Although Smith and Wellesley also offered academically rigorous courses equivalent to those taken at the prestigious male universities, they also held as their mission an emphasis on preserving qualities seen as female virtues in the 19th century (see Part One). For example, in her bequest for Smith College, Sophia Smith stated:

I would have the education suited to the mental and physical wants of women. It is not my design to render my sex any the less feminine, but to develop as fully as may be the powers of womanhood, and to furnish women with the means of usefulness, happiness, and honor now withheld from them.

As a result, Smith College offered an unusual combination, but it was a combination more agreeable to a skeptical public than the Vassar experiment had been. Smith had one of the most difficult entrance examinations of any women’s college at the time, requiring mastery of:

…arithmetic; Geography; the construction of the English language, including Orthography and Orthoepy; general outlines of History; the Latin and Greek grammars; the Cataline of Sallust; seven orations in Cicero; the first six books of Virgil’s Aeneid; three books of Xenophon’s Anabasis; two books of Homer’s Iliad; algebra to Quadratic Equations; and two books of Geometry.

However, at the same time, Smith required pupils to live in residence halls where they were expected to perform all of their own housekeeping duties, including cooking and cleaning, in order to prevent students “getting too carried away by their classwork”. The ultimate aim at Smith was to produce a new type of woman—the college woman—who was intellectually equal to men, but “socially different to, and deferential to, men”.

The only other option for higher education available to women in the Northeast when our hypothetical Sara would have been attending college was the first “affiliated” women’s college that opened in 1879: the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women, otherwise known as the Harvard Annex. Although Radcliffe, as the college would later be renamed, gained a reputation as an elite institution in the 20th century, for the first few decades after its opening the education it offered was far inferior to that available at Harvard, despite its instructors being Harvard Professors. In the 19th century, the college was primarily attended by local girls who could not afford to go to other women’s colleges located further afield, and degrees were not granted until 1893 when the Harvard Corporation agreed to a famous compromise that allowed its diplomas to be countersigned by the President of Harvard.

A Vassar Education

With these options before her, it seems most likely that our hypothetical Sara would have chosen to go down the Vassar path, not only because it seems unlikely that she would have approved of the intellectually equal but socially deferential attitude of a college like Smith, but also because Vassar could have offered her practical advantages the other colleges lacked. Many college attendees chose colleges located in or near their hometowns during this period, both due to the difficulty of transportation and a desire to stay close to family. As Sara was close to her father and her mother was an invalid, close proximity to home may have played a role in her choice of college, too; and given Vassar’s location in Poughkeepsie and the Howard family estate’s location in nearby Rhinebeck, Vassar seems like a logical choice. It is also worth noting that it is possible that Sara’s father may have been associated with the college in some way as well. Girls’ letters from this time describe the occasional excursions for students and faculty to the local estates of trustees.

With these options before her, it seems most likely that our hypothetical Sara would have chosen to go down the Vassar path, not only because it seems unlikely that she would have approved of the intellectually equal but socially deferential attitude of a college like Smith, but also because Vassar could have offered her practical advantages the other colleges lacked. Many college attendees chose colleges located in or near their hometowns during this period, both due to the difficulty of transportation and a desire to stay close to family. As Sara was close to her father and her mother was an invalid, close proximity to home may have played a role in her choice of college, too; and given Vassar’s location in Poughkeepsie and the Howard family estate’s location in nearby Rhinebeck, Vassar seems like a logical choice. It is also worth noting that it is possible that Sara’s father may have been associated with the college in some way as well. Girls’ letters from this time describe the occasional excursions for students and faculty to the local estates of trustees.

Although Vassar’s admission criteria stated that girls needed to be at least fifteen years of age and to have passed the entrance examinations in “the ordinary English branches, namely, Arithmetic, Grammar, Geography, and Elementary History”, a strong foundation in Latin and French grammar was necessary as well, and a large number of girls needed to take special preparatory courses in these subjects to reach the standard required for admittance into the Bachelor of Arts program. Indeed, the standard of applicants was so poor in the early years of the college due to inadequate high school education that the college was forced to open a preparatory division with curriculum that lasted for two years (extended to four years in 1874) in which the girls studied Latin, ancient history, physical geography, botany, rhetoric, algebra, French, German, and Greek. The preparatory school was finally closed in 1888 when the college trustees realised Vassar was functioning more as a preparatory school for other women’s colleges (girls were attending Vassar for four years of preparatory school before moving onto Smith or Wellesley) than as an institution for collegiate instruction.

Nevertheless, the college’s degree program was of a high standard for the period, although only two streams—classical or scientific—were offered, and there were no specific majors. Returning once more to Margaret Floy Washburn’s memoirs, we find a description of the curriculum from the 1880s when she attended the college:

At this time there were no ‘majors’ in the Vassar curriculum. English, mathematics, Latin, a modern language, physics, and chemistry were required through the sophomore year; psychology, so-called, and ethics in the senior year; there was no requirement of continuity in any other subject. So far as there was continuity in my own studies, it lay in chemistry and French.

Margaret went on to provide a vivid description of the chemistry, French, and Greek Professors who were active during her years at college, and who would have also been active during the years that our hypothetical Sara would have attended:

Professor LeRoy Cooley taught chemistry and physics in crystal-clear lectures: his favorite word was ‘accurate,’ which he pronounced ‘ackerate,’ and I have loved, though by no means always attained, ‘ackeracy’ ever since … French was admirably taught by two alternately kindly and ferocious sisters, Mlle. Archert and Mme. Guantieri, known to the students as Scylla and Charybdis: from the beginning no English was ever heard in the classroom, an unusual requirement in those days … In [my junior] year, too, I began the study of Greek: Professor Abby Leach was a skilful teacher of its grammar, and brought the little group of my classmates in two semesters to the point where they could join the incoming freshmen who had had two years’ preparation.

In keeping with the college’s rigid curriculum, life for the students followed an almost military schedule. One student from 1866 described her daily timetable which began at 6am every day and ended at 10pm. She explained that breakfast was the only meal where students were permitted to leave the dining hall once they had finished eating. Each day also included two periods of “silent hour” for prayer or bible study, two chapel attendances, an hour of enforced outdoor exercise (usually involving walking through the woods surrounding the college or gathering apples in local orchards), and only 40 minutes of free time. Despite this rigid regime, many of the girls made their own fun. Their letters include frequent mentions of tricks played on each other, sneaking into the rooms of their friends after lights out, making candy in the kitchens, and roasting chestnuts on gas burners.

In keeping with the college’s rigid curriculum, life for the students followed an almost military schedule. One student from 1866 described her daily timetable which began at 6am every day and ended at 10pm. She explained that breakfast was the only meal where students were permitted to leave the dining hall once they had finished eating. Each day also included two periods of “silent hour” for prayer or bible study, two chapel attendances, an hour of enforced outdoor exercise (usually involving walking through the woods surrounding the college or gathering apples in local orchards), and only 40 minutes of free time. Despite this rigid regime, many of the girls made their own fun. Their letters include frequent mentions of tricks played on each other, sneaking into the rooms of their friends after lights out, making candy in the kitchens, and roasting chestnuts on gas burners.

Weekends were a little freer for the students, with ample time on Saturdays for letter writing or visiting Poughkeepsie for shopping or church. By the late 1870s, any girl with a letter of parental consent was allowed to go out alone on weekends without a chaperone. In addition to letter-writing and excursions, the students organised a wide variety of organisations ranging from literary, floral, and missionary societies, the Shakespeare society, and various sporting societies to take up their time on weekends as well. Sport also played a prominent role in the life of the college from its earliest days, something that our hypothetical Sara—who we know was athletic—would most likely have enjoyed. Gymnastics, croquet, archery, rowing, skating, tobogganing, tennis, and basketball were all offered by the college in the mid-1880s.

To Be Continued

Strict though Vassar may seem by modern standards, four years of life at a women’s college like Vassar offered young women something that they could get nowhere else during the late 19th century. After graduating from college, however, our hypothetical Sara would have faced one of the most difficult phases of her life. As a result, the final part in this series will overview the life choices female college graduates faced during the years immediately following college, including the family versus social claim, the marriage versus career dilemma, and the limitations of professions open to young women in the 1880s and 1890s.

Footnotes

1. Until schools became bureaucratised, less experienced male teachers typically preferred the higher levels of authority rural schools provided.

2. It should be noted that many girls from the upper-classes at this time went to finishing school rather than college. However, as we are told explicitly that Sara went to college, I have chosen not to detail the finishing school option in this blog series.

Sources

- Amneus, C. (2003). A Separate Sphere: Dressmakers in Cincinnati’s Golden Age, 1877-1922 ; with essays by Anne Bissonnette, Marla R. Miller, and Shirley Teresa Wajda. Texas, United States: Texas Tech University Press.

- Buck, P. (1962). Harvard attitudes toward Radcliffe in the early years. Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 74, 33-50.

Gordon, S. H. (1975). Smith college students: The first ten classes, 1879-1888. History of Education Quarterly, 15(2), 147-167. - History of Regents Examinations: 1865 to 1987. (1987). Retrieved November 23, 2013, from link.

- Scarborough, E., & Furumoto, L. (1989). Untold Lives: The First Generation of American Women Psychologists. New York, NY, United States: Columbia University Press.

- Schwager, S. (1987). Educating women in America. Signs, 12(2), 333-372.

- Vassar Encyclopedia. (2005). Retrieved October 13, 2013, from link.

- Washburn, M. F. (1932). Some recollections. In C. Murchison (Ed.), A History of Psychology in Autobiography, Vol II. International University Series in Psychology (pp. 333-358). Worchester, MA, United States: Clark University Press.