In this blog post we will discuss the weaponry and use of military technology presented in The Legend of Broken. The novel takes place near the Harz Mountains in Germany at a time after the fall of the Roman Empire and before the rise of Charlemagne in the later part of the eighth century. We will use the term “dark ages” to refer to the time period between A.D. 400 through 800, which has been also called the Early Middle Ages and the Migration Period.1 In this post we shall address what weapons were available during this time period and how they were used in battle.

The majority of weapons used in the Early Middle Ages and onward include the short- and longbow, the sword in its many variations including daggers and long knives, spears, lances, and halberds, as well as heavier siege artillery such as the siege tower and catapult with its variants, the ballista and trebuchet. Armor came in various fashions and styles, but almost always included the helmet, greaves for leg armor, and scale, chain mail or whole plate armor to cover the torso – made of any number of materials available at the time including iron.

Armor

The accoutrements of a Dark Ages warrior usually consisted of a helmet, body armor including the arms and legs, and possibly a shield to deflect bladed weapons and small artillery. A type of plate armor known as greaves — also called sarbein in The Legend of Broken (632) — were worn on the legs to protect the shins from blunt force. Chain mail was in much use covering the torso from shoulders to hips. Because chainmail could be penetrated by a well placed arrow, scale mail was much more effective in weapon deflection, but neither were more safe and damage resistant than plate armor, a whole piece of metal armor worn over the torso. The spangenhelm is very similar to the helmet mentioned in the novel, and is referred to by native etymology in the endnotes (667). One particular helmet found worn by a Frankish warrior of the sixth century provides insight to what Germanic warriors of this time and region would have utilized.

The accoutrements of a Dark Ages warrior usually consisted of a helmet, body armor including the arms and legs, and possibly a shield to deflect bladed weapons and small artillery. A type of plate armor known as greaves — also called sarbein in The Legend of Broken (632) — were worn on the legs to protect the shins from blunt force. Chain mail was in much use covering the torso from shoulders to hips. Because chainmail could be penetrated by a well placed arrow, scale mail was much more effective in weapon deflection, but neither were more safe and damage resistant than plate armor, a whole piece of metal armor worn over the torso. The spangenhelm is very similar to the helmet mentioned in the novel, and is referred to by native etymology in the endnotes (667). One particular helmet found worn by a Frankish warrior of the sixth century provides insight to what Germanic warriors of this time and region would have utilized.

Swords and Bladed Weapons

In the novel, The Legend of Broken, a few types of swords mentioned are “raiding”, “marauder”, and “short-” swords, or what is also known as an arming sword. Although there are several types of swords, as catalogued by Oakeshott’s typology2, we will focus only on those mentioned in the novel. During the Migration Period in the Germanic region, the sword most often in use was a type of Roman sword known as the spatha, a long, straight sword, which is possibly a descendant of the Roman gladius. The majority of swords at this time were made of bronze or iron available in the region, created by methods known as pattern-welding or damascening — a process of inlaying various metals into one another.

In the novel, The Legend of Broken, a few types of swords mentioned are “raiding”, “marauder”, and “short-” swords, or what is also known as an arming sword. Although there are several types of swords, as catalogued by Oakeshott’s typology2, we will focus only on those mentioned in the novel. During the Migration Period in the Germanic region, the sword most often in use was a type of Roman sword known as the spatha, a long, straight sword, which is possibly a descendant of the Roman gladius. The majority of swords at this time were made of bronze or iron available in the region, created by methods known as pattern-welding or damascening — a process of inlaying various metals into one another.

Historians have speculated that swords and other bladed war implements were named for the peoples who used them. The Saxons favored the seax, or sax, a type of dagger with wooden or horn hilt used by the Germanic people. Spear implements such as the Frakki or frakka or “Francisca” were used by the Franks during the Merovingian period. The Longobardi were supposedly named — by the Romans — after their long-handled axe, or the long halberd.

Employment of the economic and easily crafted spear was used by cavalry and infantry. The spear consisted usually of only two parts, a leaf-shaped blade wedged into a long wooden staff. Another member of the long-hafted bladed weapon family was the halberd, typically a long handled implement with a metal axe head which was used to cleave and chop.

Bows

There are a few types of bows, but those most commonly found in this particular era and region, according to archaeological record, are short- and longbows, and composite bows. The longbow gets its name from its length which is usually similar in height of the person wielding it (between five and six feet). It is typically constructed from a single piece of wood, usually of the yew tree, but other wood materials have been found just as hardy. The composite bow’s design and construction consists of various materials laminated together such as wood, and animal horn and sinew. Both long- and composite bows were used by infantry soldiers and highly trained horse-mounted archers. Longbowmen required years of training to develop the strength to use a longbow effectively.

In later centuries, the crossbow would eventually replace the longbow completely mainly because of its ease of use and its efficacy of penetrating chain mail due to the mechanical advantage inherent in the mechanism of loading the weapon.

Cavalry and Infantry

Horsemen were considered the elite of any military operation in the Dark Ages especially since owning a horse was quite expensive and indicated a man of wealth. The cavalry could be used for both scouting and for combat. Horses were much smaller and sturdier, almost pony-like, but still gave the soldier a great advantage in battle, unlike its larger successor that came along later in the High Middle Ages. Cavalry fought atop horses using lance and spear, and if trained, with short bow. The speed and force of a mounted warrior made them formidable, but easily knocked from their mounts because of one glaring missing item, the stirrup. Historians believe that despite the stirrups introduction by Central Asia invaders, the stirrup may not have seen wide use until Charles Martel’s time in the eighth century, or possibly even later during the Carolingian dynasty.

Infantry was relatively larger than the cavalry for obvious reasons, and were fitted with chain, scale, or plate armor, short or long swords, daggers, shields, and a long-handled axe, the halberd. Both groups were successful in battle, but the cavalry proved to be faster and more forceful thanks to the introduction of stirrups.

Siege Equipment

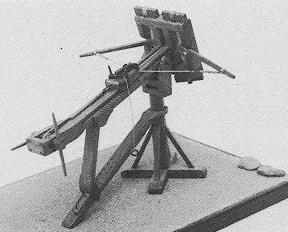

In the novel, the siege that takes place against the city of Broken is achieved by a spectacular military machine known as the ballista, or ballistae in plural form. Like a good many weapons in the early Middle Ages, the ballista is an early Greek development derived from the handheld crossbow, gastrophetes. The earliest forms of this war machine were made of wood with iron fittings, freestanding yet mobile. A mechanism employing a winch-based ratchet system allowed warriors to insert large projectiles from rocks to crafted missiles such as the massive iron bolt mentioned in The Legend of Broken (304) as well as incendiary weapons which we be discussed later on.

In the novel, the siege that takes place against the city of Broken is achieved by a spectacular military machine known as the ballista, or ballistae in plural form. Like a good many weapons in the early Middle Ages, the ballista is an early Greek development derived from the handheld crossbow, gastrophetes. The earliest forms of this war machine were made of wood with iron fittings, freestanding yet mobile. A mechanism employing a winch-based ratchet system allowed warriors to insert large projectiles from rocks to crafted missiles such as the massive iron bolt mentioned in The Legend of Broken (304) as well as incendiary weapons which we be discussed later on.

Another type of siege machine employed throughout the Middle Ages include the trebuchet, a powerful catapult-like weapon that used counter weights instead of the ratchet system to loft heavy projectiles. The following video provides a brief look at how a modern trebuchet system works with two people on either side pulling ropes that would disengage a ring holding the lever that would launch a projectile through the air.

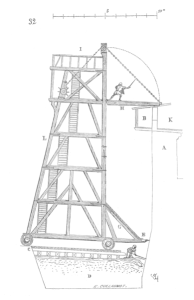

Siege towers were also used as a means to breach city barriers or castle walls without warriors taking on much personal damage. Once the towers were moved into place, a ramp would come down over the castle walls releasing a slew of armed and armored soldiers.

Siege towers were also used as a means to breach city barriers or castle walls without warriors taking on much personal damage. Once the towers were moved into place, a ramp would come down over the castle walls releasing a slew of armed and armored soldiers.

Incendiary Weapons

Artillery in the Middle Ages refers to anything that does not use fire power as a means of projection such as projectiles launched by ballistae.3 However, this period is not without its use of fire weapons such as flaming arrows which were usually dipped in oil or any other flammable liquid, then set aflame. Cauldrons of hot oil or boiling water were also used to prevent sieges by foot soldiers, poured down upon intruders from castle walls.

One particular incendiary weapon used in The Legend of Broken and shrouded in mystery even to this day is Greek fire, or as the novel refers to it, fire automatos, or automatic fire (606). Although the composition of Greek fire is still under much speculation4, the concoction was considered self-igniting and could exist even on the surface of water. This type of liquid incendiary was a state secret of the Byzantine military, but the recipe was lost over multiple generations.

Though aptly named, the minimal archaeological evidence of the Dark Ages provide of us with some insight into the peoples and their cultures in this period, particularly that of their military technology and prowess, making the era less dark, yet considerably dim. For further reading on the topic of Middle Ages, weapons and culture of early Western and Eastern European peoples, a list of recommended titles is provided below.

End Notes

1. Many modern historians refer to the Dark Ages as the time spanning from the fifth century to the eleventh century. It has been to the consternation of many historians that this era in particular, especially in Europe, is without much in the way of detailed documentation, although literary works seem to outweigh that of archeological evidence.

2. Ewart Oakeshott’s typology consists of thirteen types of swords which includes their sizes and shapes and from what materials they were made.

3. Fire powered artillery came by way of the Chinese as early as the ninth century with the design of bombs and natural tube flamethrowers purportedly used by the Tang and then later the Sung Dynasty.

4. Historians confer perhaps sulphur in combination with oil, bitumen, and saltpeter were used in creating Byzantium Greek fire.

Recommended Reading

- Barbarians to Angels: The Dark Ages Reconsidered by Peter S. Wells

— a quick and light read covering recent archaeological evidence to prove the Dark Ages were not so dark after all. - Ancient and Medieval Warfare by Elmer C May, Gerald P Stadler, John F Votaw

— a survey of military arms and tactics complete with maps of battles. - Warriors of the Dark Ages by Jennifer Laing

— a brief yet impressive overview of the real lives of tribes in Europe. - The Archaeology of Weapons by Ewart Oakeshott

— a comprehensive and technical text on ancient weaponry.

Bibliography

- Carr, Caleb. The Legend of Broken. New York: Random House, 2012. Print.

- Crabtree, Pam J. “Dark Ages, Migration Period, Early Middle Ages.” Ancient Europe, 8000 B.C. to A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Ed. Peter Bogucki and Pam J. Crabtree. Vol. 2: Bronze Age to Early Middle Ages (c. 3000 B.C. – A.D. 1000). New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2004. 337-339. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 30 Aug. 2013.

- Gabriel, Richard A. “Medieval Weapons.” World History: Ancient and Medieval Eras. ABC-CLIO,2013. Web. 30 Aug. 2013.

- Hackett, Jeremiah, et al. “The Battlefield: Tactics and Weapons.” World Eras. Vol. 4: Medieval Europe, 814-1350. Detroit: Gale Group, 2002. 209-211. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 30 Aug. 2013.

- May, Elmer C, Stadler, Gerald P, and Votaw, John F. Ancient and Medieval Warfare: The History of the Strategies, Tactics, and Leadership of Classical Warfare. New Jersey: Avery Publishing Group, 1984. Print.

- Oakeshott, Ewart. The Archaeology of Weapons: Arms and Armor From Prehistory to the Age of Chivalry. 1960. New York: Boydell Press, 1999. Print.

- O’Connell, Robert L. Soul of the Sword: An Illustrated History of Weaponry and Warfare from Prehistory to the Present. New York: The Free Press, 2002. Print.

- Wells, Peter S. Barbarians to Angels: The Dark Ages Reconsidered. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2008. Print.